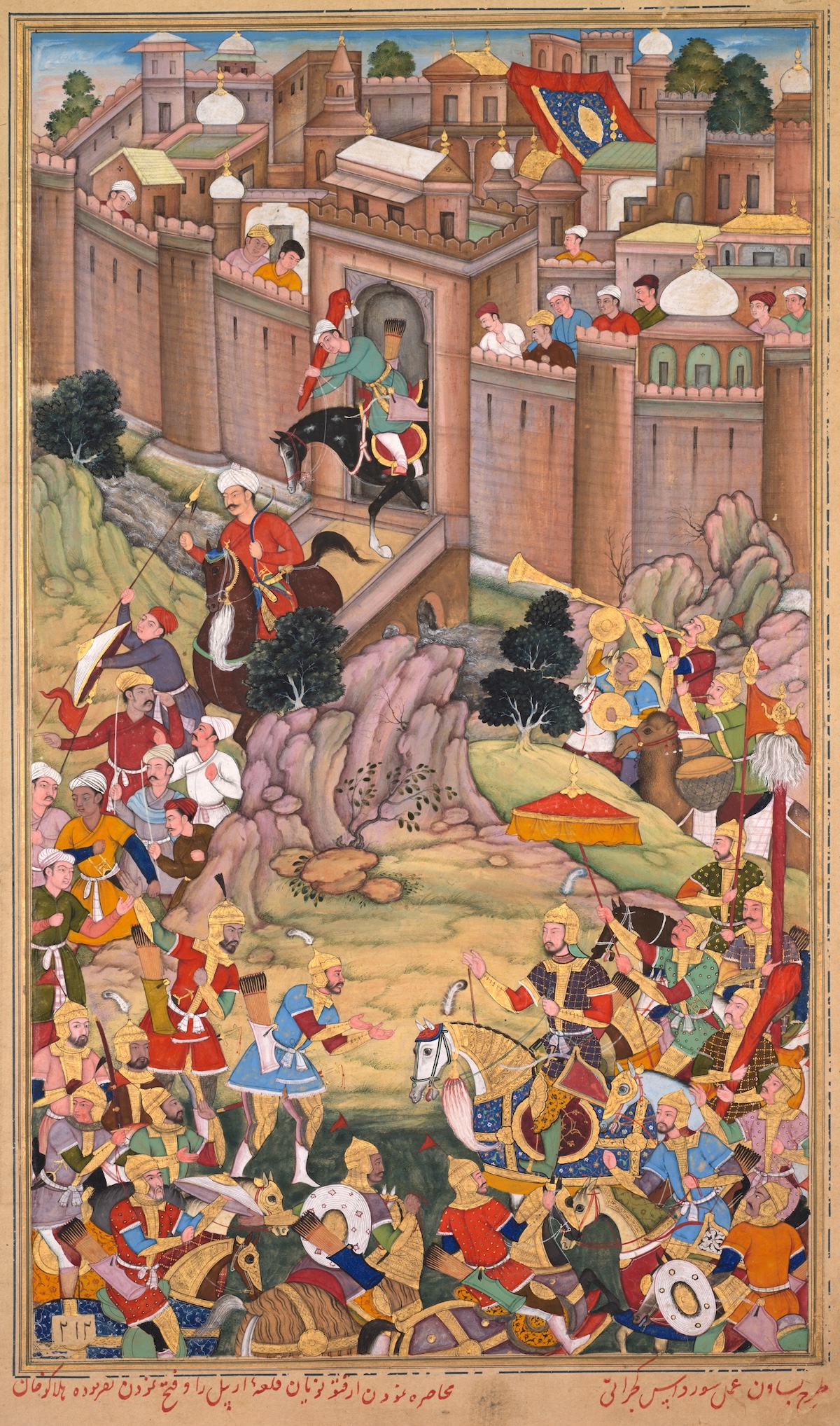

Hulegu the Mongol

Unlike his grandfather Chinggis Khan, the Mongol ruler Hulegu Khan is little known in the West. But his destruction of two Islamic empires gave him a notoriety that persists to this day.

In November 2002, just months before the American-led invasion of Iraq, Osama bin Laden released a tape in which he excoriated the administration of the former US President George H.W. Bush. The leader of Al-Qaeda claimed that members of the Bush government had killed more people in Baghdad and destroyed more of the city’s buildings ‘than Hulegu of the Mongols’. He offered no further information about who Hulegu was. He may have assumed, perhaps correctly, that most people in the Islamic world knew of the great Mongol warrior. Few westerners seemed even to have heard of him.