How Ancient Greece Shaped the British Raj

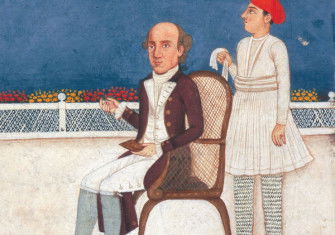

British agents of empire saw their actions in India through the texts of their classical educations. They looked for Alexander, cast themselves as Aeneas and hoped to emulate Augustus.

The British colonisers who travelled to India from the 18th century onwards were steeped in the Classics; they knew their Greek and Latin (if not the languages of India) and quoted liberally from Horace and Virgil. Not all Britons, of course – but it was not a small contingent who took ancient Greece and Rome with them to the subcontinent. In part, Classics was an affectation; speaking Latin was a sign that you were polished, well read and sophisticated, and acting like a gentleman was important to English self-regard during the Raj. But connections with Greece and Rome went deeper: the British saw their actions in India through the lens of their classical educations and understood their decisions in the light of Graeco-Roman antiquity. Some imagined themselves as marching in the footsteps of Alexander the Great, while others preferred Julius Caesar or Augustus. For some, the epic poems of Homer bore startling similarities with Sanskrit epics and were a basis for cultural comparison; for others, Virgil’s Aeneid offered guidance on how to be imperial and civilised at the same time.