The Hanseatic League: Europe’s First Common Market?

In the 13th century a remarkable trading block was formed in northern Europe. The Hanseatic League prospered for 300 years before the rise of the nation-state led to its dissolution.

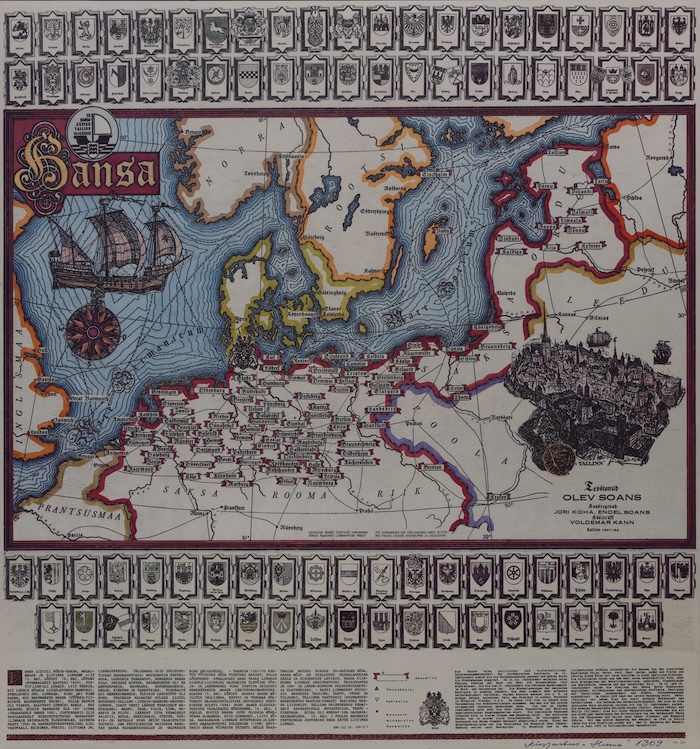

The Hanseatic League, or Hansa, began as a northern European trading confederation in the middle of the 13th century. It continued for some 300 years. Its network of alliances grew to 170 cities and it protected its interests from interfering rulers and rival traders using a powerful fleet financed by its members. Given the limits of medieval communications, it developed a modest degree of political cohesion through its parliament, even if its increasingly diverse membership struggled to agree upon common policies. Only the evolution of nation states and rival international businesses led to the Hansa’s demise three centuries later.

The League’s creation reflected the weakness of medieval governments and the divergent interests of city dwellers and the feudal overlords with whom they were often in conflict. In the middle ages, the areas now known as Germany, Poland, the Baltic States, the Netherlands, Belgium and much of Russia consisted of a multitude of territories owing allegiance to a variety of kings, margraves and dukes often from remote locations, and to chivalric orders such as the Teutonic knights. The main activities of the groups of nobles involved marrying and feuding with one another and raising taxes from their subjects. They were rarely noted for their interest in trade except as a source of taxation.

It was for this reason that a number of cities’ prominent merchants came together in a loose confederation whose main aim was to share the risks of trading, the hazards of travel and the problems of dealing with quarrelsome overlords. One of the early provisions of the League dating from 1296, which clearly shows the independence of Hansa members from their respective rulers, required members to support one another in such conflicts, though a clause in the agreement tactfully added:

If the conflict is against a prince who is lord of one of the cities, this city shall not furnish men but only give money.

The origins of the League can be traced to the German city of Lübeck, strategically placed at the western edge of the Baltic at the foot of the Danish peninsula. In 1226 the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II had declared Lübeck an Imperial City, owing allegiance only to the emperor himself. Since Frederick, like his successors, was normally far from the city pursuing quarrels with popes and other magnates, the merchants of Lübeck were freer than many city dwellers to pursue their own interests which revolved around the herring fisheries of the Baltic. To preserve the herrings they needed access to salt which was found in the vicinity of Kiel. In the late 12th century Hamburg and Lübeck had begun to trade together along the ‘salt road’ through Kiel and by 1259 Cologne, Rostock and Wismar had joined the confederation. This date, 750 years ago, is widely regarded as the origin of the Hanseatic League.

The origin of the term ‘Hansa’ is disputed, being variously attributed to a trading guild, a tax paid by communities wishing to enter the League, or an armed band formed to protect traders.

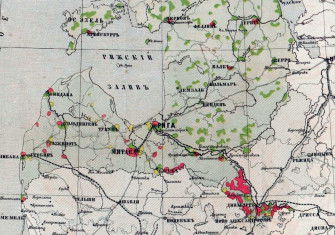

By 1400, the League extended as far as Novgorod, Riga and Krakow, now respectively in Russia, Latvia and Poland. Krakow, in particular, had a large community of German merchants, traders and bankers. In 1356, the League established a Diet, or parliament, which first met in Lübeck, where representatives of the cities discussed common approaches to such matters as piracy, trading partners and the ambitions of sovereigns. But conflicting interests precluded any serious moves towards cohesive policies of a broader kind.

The League was never a coherent political organisation. A decision to join or leave was determined by the trading interests that the citizens had at the time and also by the strength or weakness of local noble rulers. There was never a clearly defined administrative centre or system for raising taxes and its Parliament met at whichever location was convenient for those cities who were interested in the matters to be discussed. Lübeck was used as a meeting place more often than others because of its relatively central position and its long and active involvement in the League's interests. In the face of an external threat the cities whose interests were most at stake would come together in a brief phase of unity to agree common policies which usually took the form of imposing tariffs or, in extreme circumstances, the waging of war. There was no Hanseatic army or navy as such. Like the fleet which, under Elizabeth I of England, defeated the Spanish Armada, a fleet or land force would be assembled from the merchantmen and citizens of the cities concerned, financed by a tariff on appropriate commodities. Mercenaries also took part in such campaigns.

Thus in 1361 the League took up arms against King Valdemar of Denmark who attacked the Hanseatic city of Visby on the Swedish island of Gotland because he was concerned by the restrictions the Hansa had placed on Danish trade. The survival of Visby as an independent unit was critical to thefortunes of the League – its strategic position commanded the shipping routes between the Baltic communities and the North Sea through which Hansa merchants carried grain, metals, hides and English wool.

Over 70 cities in the League contributed to Visby’s cause and Valdemar was defeated. The resulting Treaty of Stralsund in 1370 was a highwater mark of the League’s history and illustrated both its power and arrogance. Free passage though ‘the Sound’ between Denmark and Sweden, giving access to the Baltic, was guaranteed for Hansa ships (though not for others) and the League was also granted the right to approve or veto the Danes’ choice of king.

The League also sprang to the defence of Danzig (now Gdansk) on the occasions when kings of Poland tried to undermine its independent status and annexe it to their own territories.

In 1368 the League flexed its muscles in its relationship with Norway. Dependent upon imported grain to feed its population, Norway, in exchange, exported fish, butter and hides. The Hansa came to dominate the grain trade and established a Kontor, a ‘counter’ or trading post, in the Norwegian port of Bergen, which became a German settlement. When the Norwegians resisted the demands of the Hansa for trading privileges which excluded the rights of others, notably English and Dutch merchants, to trade with Norway, the Hansa fleet simply blockaded Norwegian ports to prevent the importation of grain. The Norwegians were forced to concede. Subsequently, the German wharf at Bergen became known to Norwegians as ‘The Lice Wharf’, an expression which reflected their opinions of the persistent and irritating intruders.

The protectionist stance of the League was also evident in its decision in 1356 to expel, temporarily, the member city of Bremen because its merchants had offered favourable trading terms to merchants from Flanders, contrary to the wishes of the Diet.

The League never had a clearly defined membership though Lübeck and Hamburg remained at its core throughout. Other cities came and went according to their interests at the time.

One of the League’s most successful joint enterprises was in shipbuilding: its Baltic Cog was tailor-made for the shallow waters of the Baltic coastline, being a flat-bottomed vessel with extensive cargo capacity. The cogs were built mostly in Lübeck and Danzig and were sold throughout Europe, including in the Mediterranean. In the 14th century the cog was replaced by a larger version called the Holk (hulk) which could transport as much as 300 tons of freight. The League also produced warships, with successful campaigns being waged with English help against pirates between 1394 and 1420 . In the 16th century the largest ship in the world at the time was the Hansa’s Adler von Lübeck.

The League set up Kontors in many European towns outside its membership. There were several in East Anglia, including Norwich, Boston and Bishop’s Lynn (later King’s Lynn) whose medieval Hansa warehouse has been restored and now serves as the town’s register office. One of the most important and extensive Kontors was London’s ‘Steelyard’, established in 1320 on the Thames just west of London Bridge and close to the home of the customs officer Geoffrey Chaucer. The Steelyard contained a warehouse, weighbridge, church, offices and several dwellings for German merchants. It was also known as the Hall of the Osterlings to reflect the fact that its residents came from the eastern edge of Europe. This may be the origin of the word ‘sterling’ to describe a sound currency. The traders in the Steelyard also brought with them the word ‘shilling’, derived from skilling, a unit of currency used in Gotland.

The Hansa in London enjoyed a privileged position within the League which owed something to the fact that the city of Cologne had contributed to the ransoming of Richard I in 1194 before the Hansa was created but more to the fact that Hanseatic cities provided finance for Henry III in his conflict with Simon de Montfort which climaxed at the Battle of Lewes in 1264. At a time when the process of raising taxes was rudimentary, arbitrary and unpopular, the availability of loans or bribes in return for valuable trade concessions promoted the Hansa’s interests above those of local traders.

The early phase of the Hundred Years’ War waged in France by Edward III from 1337 was financed by Hansa merchants, Edward’s crown jewels being held in pawn from 1339 to 1344 in the Hanseatic city of Cologne. As a result, the German merchants in London’s Steelyard were granted concessions on valuable tin mines in Cornwall and such favourable trading terms in England’s flourishing wool trade that by the 16th century to the considerable irritation of English merchants they were handling over 90 per cent of wool exports.

In 1381 the London Steelyard was wrecked by followers of Wat Tyler during the Peasants’ Revolt and it was besieged again in 1492 by Londoners who resented its trading privileges. On that occasion it was stoutly defended and continued to prosper into the 16th century. In 1532 its merchants could afford to pay Holbein to paint two pictures depicting the Triumph of Poverty and the Triumph of Riches to decorate its hall. In 1526 the Steelyard was raided by a party led by Sir Thomas More in search of heretical Lutheran tracts; More’s master, Henry VIII, was then still a Catholic and the scourge of Protestant heresy. By this time the Steelyard, which was used by merchants from many Hanseatic cities, had become virtually a power in its own right, independent of the cities from whence the merchants came.

The decline of the Hansa coincided with several factors that came together in the 16th century. The first was the rise of nation states and princely rulers who wished to exercise control over their own trading interests and resented the protectionist practices of the Hansa. In England the interests of the Hansa came into conflict with the Company of Merchant Adventurers of London. Established in the 13th century, the company received a new charter from Henry VII in 1505 which effectively gave its members a monopoly of the export trade in cloth among English merchants, traders from other cities like Norwich having to pay the London company for the right to export their own produce.

"In the 16th century, the centre of European trade moved decisively to the south and west of Europe"

The London merchants were no more committed to free trade than the Hansa and, when their monopolistic interests were in conflict with those of the Hanseatic merchants at the Steelyard, they protested. Sir Thomas Gresham (1519-79), founder of the Royal Exchange, drew Elizabeth I’s attention to the fact that the League was not only enjoying a substantial share of the export trade but that it refused to use English ships. In 1598 Elizabeth expelled the Hansa from the Steelyard, though it continued to be occupied by individual merchants from Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck. It became known as the Rhenish Garden, where wines and beer from Germany could be enjoyed in the open air. Samuel Pepys makes several references in his diary to his use of its facilities. The Steelyard was finally sold in 1853 for £72,500 to become the site of Cannon Street station.

The decline of the Hansa was also a reflection of the fact that, in the 16th century, the centre of European trade moved decisively to the south and west of Europe, with Spain and Portugal’s opening up of the New World and the rise of the maritime nations of the Netherlands and England. At about the same time, the herring fisheries on which much of Lübeck’s prosperity had been based migrated from the Baltic to the North Sea. Most merchants in the Baltic Hansa cities realised that it was in their interests to engage in trade with the new powers, English wool and cloth being particularly desirable commodities.

A final, desperate attempt to reassert the authority of the League was made by the mayor of Lübeck, Jurgen Wullenweber, in 1534-35. He tried to form a cohesive federation of cities, led by Lübeck, to exclude Dutch and English traders from the Baltic and to prevent the shipbuilding technology developed in Lübeck and Danzig from being disclosed to the Dutch. This led to war with Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands. Wullenweber also proposed a series of even more protectionist measures whereby any cargoes from Baltic ports would have to be carried in Hansa vessels. This was a step too far and Wullenweber was arrested on trumped-up charges and subsequently executed in 1537 on the orders of Henry II, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfen-biittel.

The final factor leading to the decline of the Hansa was the growth of competition from other communities which were not bound by its rules and did not intend to allow it to interfere with their interests. Some of the most prominent were German, notably Nuremberg in Bavaria and the Swabian city of Augsburg. Both cities owed much of their success to the Fugger family, led by the formidable Jacob Fugger (1459-1525). The Fuggers were an early example of an international trading firm whose banking interests underpinned their trade in copper, wax, furs, silver, spices and anything else for which there was a market. Lübeck led the attempts to prevent the Fuggers from shipping their goods through Hanseatic towns but was eventually defeated by the financial influence of the family whose taxes and loans to kings and princes counted for more than the protectionism of Lübeck and its dwindling band of allies. Rivalries between the League’s cities ensured that its power faded in the face of nation states ruled by strong governments. The last Kontor was sold in Antwerp in 1863.

The legacy of the Hanseatic League lives on in the name of the German Bundesliga football team, FC Hansa Rostock and the Lufthansa airline, while the local governments of Lübeck, Hamburg and Bremen still describe their ports as ‘free and Hanseatic cities’. In the 1990s memories of the Hansa were revived when a Hanseatic parliament was established in Hamburg to represent the interests of small and medium-sized companies in cities in northern Germany, Poland and the Baltic States.

The League’s history invites comparison with the European Union (EU). Helen Zimmern, an early historian of the League, writing in 1889 in the aftermath of its dissolution, saw such a cooperative enterprise as evidence of ‘that federal spirit which will, beyond doubt, some day help to solve many of the heavy and grievous problems with which we of the Old World are struggling’. The EU started as a means of promoting peaceful trading relationships among its members, in particular the old enemies of France and Germany, and has attempted to develop a degree of ever greater political union among them. Like the Hansa, the EU has often promoted the trading interests of its own members at the expense of others. For example, the Steelyard’s attempts to monopolise the export of finished English cloth in the 16th century could be compared with the EU’s unsympathetic attitude towards developing economies: Africa’s raw materials are welcome in Europe but, if African producers of cocoa wish to add value to the product by processing it and turning it into a drink, they face a heavy tariff. The EU is considerably less resolute in dealing with competition from rapidly developing economic powers like Brazil, Russia, India and China.

The Hanseatic League enjoyed considerable success in protecting its interests as long as it was dealing with an assortment of quarrelling medieval magnates where its financial muscle was sufficiently strong to mask the conflicting interests of its members. It was no match for the emerging interests of nations like Britain and Holland whose governments were determined to control their own economic fortunes. Nor could it compete with the ruthless trading powers of companies like the Fuggers who did not recognise national borders. Likewise, in the 21st century the European Union is showing signs of disunity in the face of serious economic problems and has proved itself so far unable to deal with rogue organisations like bankers (and car manufacturers) who outmanoeuvre member states and play off their interests against one another. Despite the strains, the EU has shown no signs of disappearing as the Hansa eventually did but it has yet to demonstrate that it can present a united front in the face of economic challenges that are more severe than those it has previously faced.