England’s Monasteries: Gone But Not Forgotten

The Dissolution of the Monasteries by Henry VIII is a well-worn tale. Are we getting the whole story?

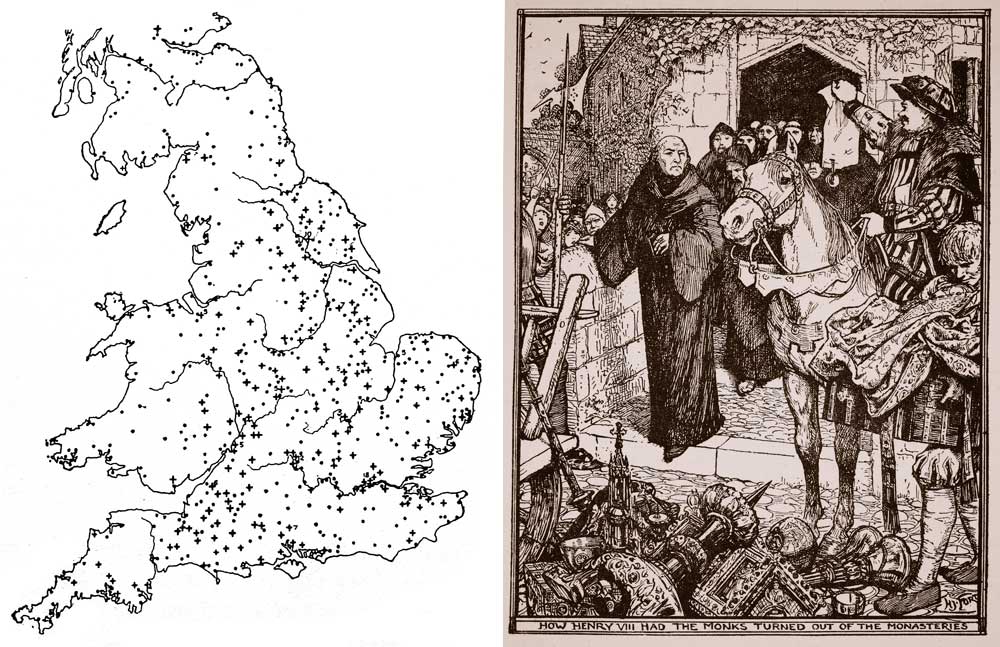

The story goes like this: in 1533 a king in need of a divorce resorted to desperate measures to ensure the future of his dynasty. After almost 25 years of marriage, despite numerous pregnancies, the union between Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon had not yielded a surviving son and heir. The king sought an annulment from the pope but was refused and so Henry cast off the yoke of Rome and made himself head of a new national church, the Church of England. This snap rejection of papal authority had profound consequences for religion and society. Roman Catholic practices and institutions came under attack. Most famously, some 800 monasteries, convents and friaries were suppressed with ruthless efficiency between 1536 and 1540. Not that anyone minded: a reputation for bad behaviour had made the religious orders unpopular in local communities. Most of the monks, nuns and friars were quietly pensioned off and their buildings systematically looted of anything of use or value, first by the king’s agents and later by local people. All in all, the Dissolution of the Monasteries was achieved with little pain and less regret. The religious houses went with a whimper, not a bang.

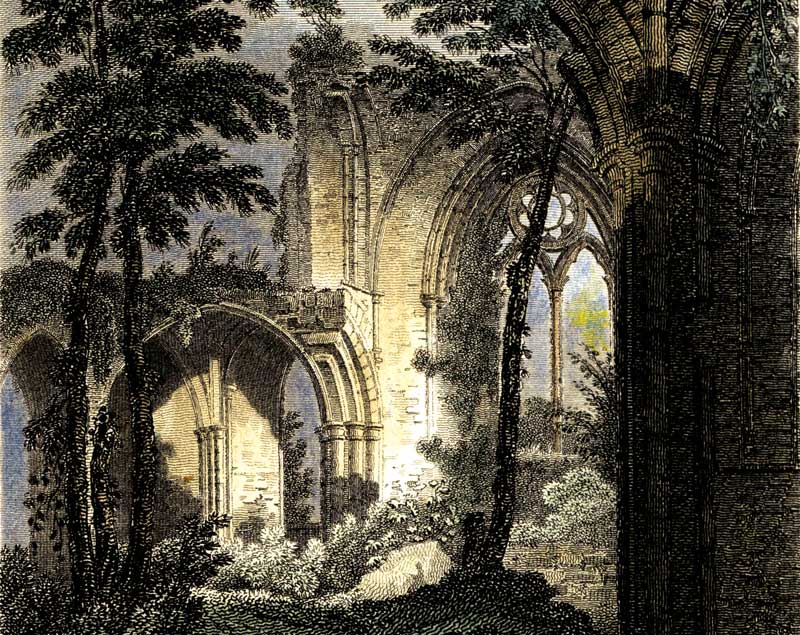

It is not hard to see why the Dissolution has captured the historical imagination. It is, after all, a good story: full of racy details about wicked monks and nuns and centred around a tabloid-worthy divorce saga. It stars larger-than-life actors like Henry and his chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, both of whom are currently riding a new wave of Tudormania, driven in no small part by the novels of Hilary Mantel. It is also an episode that feels sufficiently distant so as to be somehow glamorous and exciting, but which still feels tangible, largely because so many monastic ruins remain standing as pillars of the British heritage industry. The remnants of a lost medieval world, these ruins attest to the power and might of the Tudor state. In their fragmentary condition, they also symbolise the corruption of monasticism, which had lost its faded medieval glory by the time the looters moved in.

What more can there be to say? The answer, of course, is that this is not the whole story, nor is it the only possible telling. Yet its power and persistence are remarkable and merit investigation. The Dissolution of the Monasteries is a tale centuries in the making.

Abominable living

Early modern governments understood the power of spin. Beginning in 1535, Henry’s agents conducted a series of visits to religious houses with a view to surveying their wealth and the standards of behaviour maintained by the monks, nuns and friars. These agents reported their findings to Thomas Cromwell in London, who amassed a large volume of correspondence, which has since become one of the most significant archival collections concerning the Dissolution. These letters paint a bleak picture of 16th-century monasticism. A typical example is the case of John Reeve, abbot of Bury St Edmunds, a large and powerful Benedictine house in Suffolk. The allegations against Reeve were numerous and damning; he was said to be a chronic gambler, a bad landlord and a head of house who turned a blind eye to the sexual promiscuity of his brethren. Tellingly, it seems that Reeve was also resistant to the government’s religious reforms and remained committed to ceremonies and practices that the king’s agent, John ap Rice, deemed superstitious. We can almost hear Rice’s laughter when he tells Cromwell about the saints’ relics found at Bury, which purportedly included so many splinters of the Holy Cross upon which Jesus had been crucified that they would make a complete cross, if only the pieces could be put back together.

Reeve’s case was far from unique. Cromwell’s office received numerous reports alleging that the religious orders were guilty of sexual immorality, fraud, superstition and greed – in other words, the kind of worldly living that they had forsaken in their vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. It was on the basis of these claims that Henry VIII made the first move against the monasteries. In 1536 the first dissolutions were announced by Act of Parliament. It heralded what was supposedly a partial reform of the religious houses, in which the smaller institutions (those worth less than £200 per annum) would be suppressed and their inhabitants redistributed around the larger houses. This was a measure intended to combat the ‘manifest sin, vicious, carnal and abominable living’ that had been uncovered by the king’s agents. This was not the Dissolution of the Monasteries, but rather a rationalisation and reallocation of resources. For all anyone knew in 1536, this was the end of the matter.

Except, of course, it wasn’t. It soon became clear that the government was exceeding the terms of the Act. Waves of dissolution – including of some larger properties – took place throughout 1537 and 1538, fuelled by the accounts of monastic iniquity that were still pouring in from every corner of the country. Anti monasticism was now the quasi-official government line. There is some evidence that favourable accounts of particular houses were returned to their authors with instructions to amend them in line with the government’s message that the religious orders were corrupt. The wider public also became implicated in this campaign: some of the letters received by Cromwell were unsolicited reports from local people. Rumours about secret passages built for illicit liaisons had long plagued the religious orders, but now they acquired a new urgency and significance. Meanwhile, the government had also begun to undertake public denunciations of supposedly fake relics, such as the Rood of Grace from Boxley Abbey in Kent to which pilgrims had flocked hoping to see the likeness of Jesus move its eyes and face. It was exposed before an audience in the market town of Maidstone, where Bishop John Hilsey (himself a former Dominican prior) broke the rood apart, revealing it to be mechanical, not miraculous.

Under the weight of the criticisms levelled against them the monasteries did not last long. In the autumn of 1539 a new Act of Parliament committed the government to a policy of total dissolution. There were a couple of neat tricks written into this second Act, which was very different in tone from its predecessor. In a rather restrained fashion, the Act announced that every one of the ‘said late monasteries’ had been freely surrendered by their inhabitants ‘without constraint, coaction, or compulsion’. The first trick, then, was to make the religious orders complicit in their own demise, their quiet submission an acknowledgement of their own corruption. The second was to imply that domestic monasticism was already dead and buried. The use of ‘late’ to describe the monasteries ignores the fact that some houses struggled on for a little while after the Act was passed. The last of the abbeys, Waltham in Essex, only surrendered in March 1540.

Together, the Acts of Dissolution told a clear story. Endemic corruption had brought down the monasteries from the inside. Henry VIII’s government had tried to save the larger religious houses in 1536, but in the end it had no choice other than to accept their total surrender in 1539. The whole process was conducted very efficiently and without resistance, either from the religious orders who had so willingly given themselves up, or from members of local communities, in which the monasteries were profoundly unpopular. In this telling, the Dissolution was little more than the coda to the history of the rise and fall of English monasticism.

Plot holes

In attempting to manage how the Dissolution was received in the 1530s the Tudor government laid the foundations for how its history would be written. The government wanted people to talk about monastic corruption. It did not want people to talk about the wider impact of the Dissolution; there were orders for those speaking against the suppression of religious houses to be arrested for sedition. But, of course, there were plenty of people who did not believe the vision of the Dissolution that Henry tried to sell to them.

In 1536 rebellion was already brewing in the north of England. Under the leadership of a lawyer named Robert Aske some 9,000 people entered and occupied York in a rising known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. Their demands for the monasteries to be restored were driven by a commitment to their Catholic faith as well as a feeling that social and economic life had suffered since the suppression of local religious houses. For centuries these institutions had provided charity, hospitality and employment. Collectively, they were among the very largest landholders in the country. Now their tenants feared for their livelihoods. Even though the Dissolution was still some years from completion, Aske and the rebels believed it had changed everyday life for the worse. Their initial success at York was not to last. The rebellion was suppressed by the king’s forces and Aske was executed as a warning of what happened to those who resisted royal authority.

A similar fate awaited those members of the religious orders who opposed the Dissolution. The government’s claim in 1539 that suppressions had been conducted without violence was not entirely true. In 1537, 15 Carthusians from the London Charterhouse were either put to death or died in prison as a result of their opposition to the Dissolution; three Carthusian priors had already been executed in 1535 for refusing to acknowledge the king’s supremacy over the Church. Then, late in 1539, the abbots of Colchester, Reading and Glastonbury were likewise killed for failing to surrender their houses. In a grisly public display of state power, Richard Whiting, abbot of Glastonbury, was hanged, drawn and quartered with two of his monks at the top of Glastonbury Tor. All this took place at a moment when, as far as Henry’s public pronouncements suggested, the Dissolution was all but over.

The government also had its critics at the other end of the religious spectrum. Those who supported reform of the Church (whom we might now call ‘Protestants’, but who were then usually called ‘evangelicals’) had no problem with the idea of Dissolution in principle. But the manner in which it had been conducted caused them some anxiety. Chief among their worries was what was happening to former monastic properties. Around a third of all the land in England changed hands at the Dissolution, making it the most significant transfer since the Norman Conquest. Much of this wealth and property was funnelled into private hands. Critics argued that the riches seized from the religious houses should be put back into the Church. This was sometimes the case – not least in the form of cathedrals like Brecon, Canterbury and Durham, which had once been monastic but which still serve the present-day Church of England and Church in Wales. But the lion’s share went to the Crown and nobility, who created new homes out of ruined abbeys or bolstered their patronage networks using monastic funds. The Dissolution seemed as much an act of greed as of religious reform.

These voices, Catholic and evangelical, tell different stories about the Dissolution: as a violent assault on a great medieval institution, or as a calculated land-grab. They are less easy to find in the historical record, which is dominated by the account authored by the Tudor government. To recover these perspectives, we often have to read sources against the grain; for example, the trial reports from the Pilgrimage of Grace condemn Aske and his fellow rebels, but in doing so they also record their testimony. Or we can turn to different sources, such as the thriving print culture in which many evangelical critics aired their anxieties. When we rely on the documents created by and for Henry VIII’s government – on the Acts of Dissolution and the correspondence of the 1530s – we miss many of these threads. When modern historians retell the story with which this article began, they are the heirs of Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell.

Safe keeping

Another way of getting beyond the conventional narrative is to look later than the end of the process of Dissolution in 1540. The 1539 Act of Dissolution suggested that the religious houses were little more than shadows of a corrupt past. However, questions about the future of monasteries and monasticism were not put to rest with the physical dismantling of abbeys and convents. Perceptions of the Dissolution continued to evolve in the decades and centuries after Henry VIII’s reign.

Looking forward in time helps us to understand, above all, that the Dissolution was not simply destructive; it was also creative. Nowhere can this be seen more clearly than in the transformation of monastic buildings. Our modern obsession with ruins has obscured the fact that as many as half of all religious houses underwent some degree of adaptation or conversion for new purposes. Not until after the Blitz would England again see such extensive and animated building activity. Some monastic churches became parish churches without the need for too much alteration; other properties required more significant changes as they were converted into domestic houses or public meeting places. Private dwellings, in particular, reveal that for all those who lost out during the Dissolution there were many who made substantial gains. Between 1537 and 1547 the Lord Chancellor, Thomas Wriothesley, acquired ex-monastic properties in eight different counties. The grandest of these properties, including Titchfield Abbey in Hampshire and Walden Abbey in Essex, were transformed into magnificent country houses. Archaeologists have long understood the value of thinking in terms of phases of destruction, adaptation and re-use. These processes of architectural change effaced the memory of the monastic past, but also attest to the rising fortunes of many in the gentry community.

Interestingly, Catholic as well as Protestant families profited in this way. The official line from Rome was that Catholic occupation of former monasteries was acceptable – indeed, preferable to these buildings falling into Protestant hands – so long as they were returned to the Catholic Church at the time of its restoration in England and Wales. In the first decades after the Dissolution, this was not necessarily a vain hope. In 1547 Henry VIII was succeeded by his son, Edward VI, who died in 1553 while still a teenager, causing the crown to pass to Mary, Henry’s eldest daughter. Mary had always retained a firm commitment to her Catholic faith. After her accession she reinstated papal authority and set about reviving Catholicism. Part of this project involved encouraging people to give back abbey lands that had fallen into private hands. Mary herself set a good example by reviving a monastic presence in Westminster Abbey and returning her own monastic lands to the Church. But others were reluctant to follow suit and give up their grand new houses. When Mary died prematurely in 1558, her restoration of the monasteries had barely begun. The accession of Elizabeth I ushered in a return to Protestantism and, although papal authorities reiterated their instruction that Catholics were simply keeping monastic property safe until it could be returned to the Church, as the decades wore on this seemed increasingly unlikely. Nevertheless, for Catholics, ex-monastic houses helped to keep the idea of a monastic restoration alive well into the 17th century, at the same time as marking an improvement in the fortunes of their owners.

Divine wrath

Material gain, however, went hand-in-hand with something more sinister. The occupation of sacred space was a vexed question. The fact that abbeys and convents stood upon consecrated ground made many people uneasy. Wriothesley’s builders assured him and his wife that a chapel could be constructed in place of the abbey church that had been pulled down so that the sin of sacrilege – the desecration of sacred space – might be avoided. Such concerns seem rarely to have prevented building projects taking place, but it is clear that anxieties about the misuse of consecrated sites persisted well into the 17th century and beyond. As people became increasingly critical of the architectural destruction that had taken place in the 1530s, there developed a narrative that those who lived in converted monasteries were prone to suffering divine wrath for their sins. Failure of the family line was perhaps the most common punishment, with terrible illness and accidents following close behind. In local communities rumours circulated that converted religious houses were haunted by the ghosts of their inhabitants, ghoulish monks and nuns who paced the hallways and stairwells of these places seeking vengeance upon their new owners. As late as the early 18th century Walter Taylor, a carpenter who set to work dismantling parts of Netley Abbey near Southampton, was said to have been haunted by an apparition dressed in a monk’s habit. Taylor did not heed the ghost’s warning that mischief would befall him if he continued to pull down the old abbey chapel and, not long afterwards, he was killed when the chapel window fell on him. The locals whispered that Taylor’s death was a punishment sent by God for continuing the destruction wrought during the Dissolution. Stories such as this were not uncommon even two centuries after the religious houses had been suppressed.

It was in this context of increasingly critical perspectives on the Dissolution that some people began to revise the narrative of monastic corruption that had been the keystone of government propaganda in the 1530s. In the later 17th century the historian and antiquary Abraham de la Pryme wrote that a ‘plot’ had been laid against the religious orders and suggested that evidence of their iniquity had been vastly overstated by Henry and his agents. Around the same time Thomas Brudenell, first earl of Cardigan, was troubled by local gossip that the suppression of Hinchingbrooke Priory in Huntingdon had only been achieved because false rumours were spread about the promiscuity of the nuns who resided there. Two centuries on, with the benefit of hindsight, the Dissolution was not quite the moment of uncomplicated triumph it had once seemed. When we listen only to Henry VIII, we hear only half of the story.

Harriet Lyon is the author of Memory and the Dissolution of the Monasteries in Early Modern England (Cambridge University Press, 2021).