Felice Orsini: Striking a Blow for Freedom?

The consequences of Felice Orsini’s assassination attempt on Napoleon III were momentous and paradoxical.

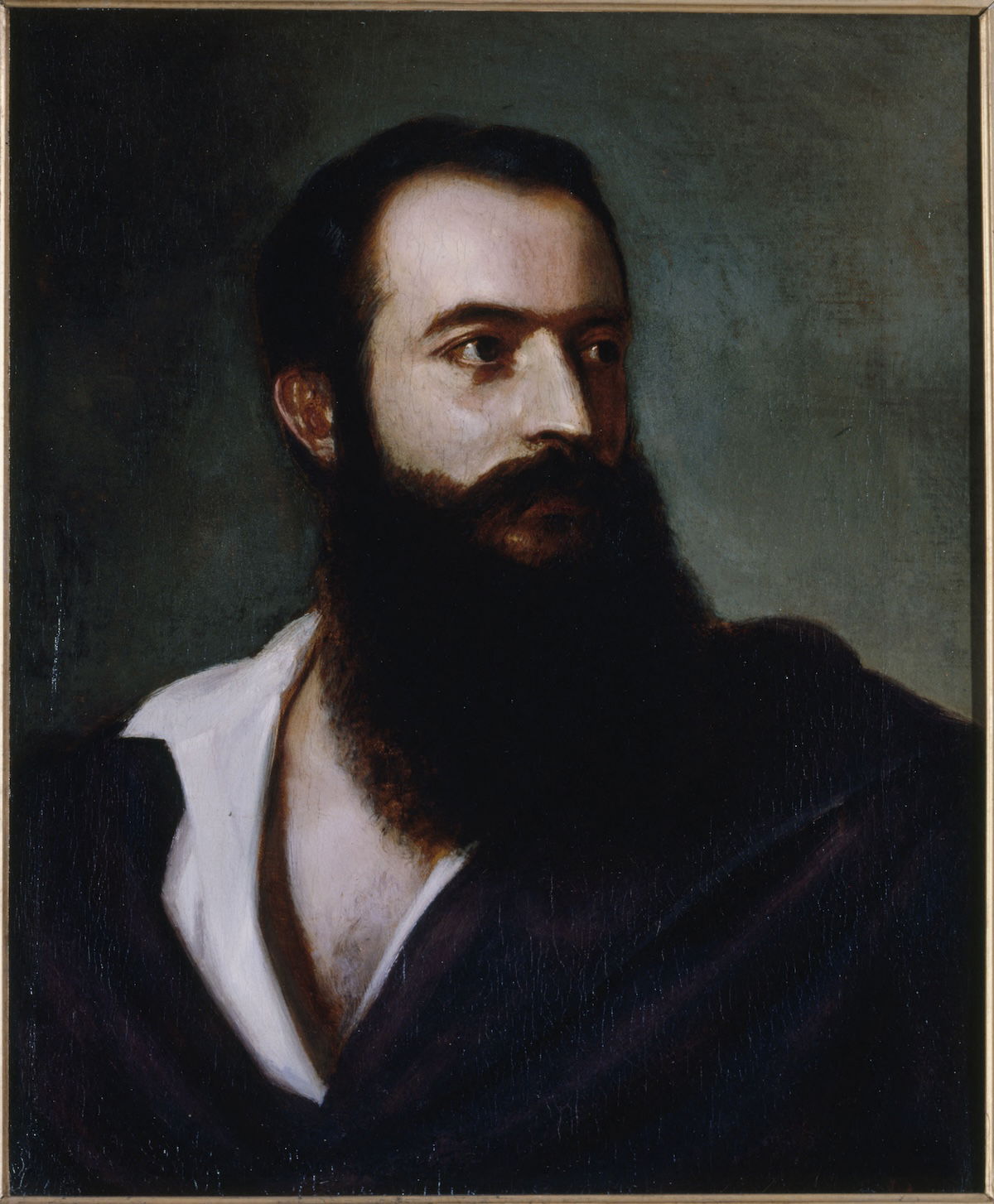

Dashing Italian patriot Felice Orsini received a rapturous welcome in England in 1856. He was the embodiment of romantic nationalism: a handsome revolutionary who had suffered for his beliefs, who had recently made a daring escape from a brutal prison.

Yet while enjoying the luxuries of free speech and political association that Britain afforded, Orsini was slipping out of the lecture circuit to create weapons of unprecedented force which were to be used in a massacre in a foreign city. His actions stimulated a debate on issues of freedom and despotism which still trouble liberal democracies today.

Orsini was born in Meldola, in 1819, in a fragmented Italy misgoverned by Austria and various local tyrants. His family had a tradition of insurrectionist politics. His ideals were those of Young Italy, that a national war brought about by continuous risings was essential to free the nation. He took part in the abortive 1848 revolution and was a deputy of the short-lived Roman Republic where he became known as ‘il bambino democratico’. He was involved in four uprisings in total, which took their toll of Italian nationalists on the scaffold, while doing nothing practical to advance the cause.

Soon exiles were spread throughout Europe, with England a favourite location where the mastermind of Italian emancipation, Guiseppi Mazzini, plotted assassination and insurrection from cramped rooms on Fulham Road, west London.

Orsini was captured by the Austrians and thrown into the prison fortress of Mantua in 1855. In a thrilling story which became the template for popular romantic notions of prison escape, he painstakingly used a tiny saw to cut through an inner, then an outer, grid of bars and climbed out of the window 100 feet high, using knotted sheets as a rope. He declared himself a patriot to a passing peasant who carried him to safety past the Austrian soldiers, while raucously singing an Italian drinking song – a sight not so uncommon in Mantua on a Sunday morning.

Orsini’s account of his escape was translated and sent to the Daily News then copied by all the English newspapers. Smuggled through Europe, the fiery patriot arrived to acclaim in England. He knew how to capitalise on his suffering to the benefit of his cause: he wrote The Austrian Dungeons in Italy in 1856, selling 35,000 copies in its first year. The Memoirs and Adventures of Felice Orsini followed in 1857.

While he toured the country speaking at meetings, he took time off to meet revolutionary activists, some of them English. Using one English sympathiser as a go-between, Orsini made contact with Joseph Taylor, a gun engineer of Birmingham, who was given a wooden model of a grenade with a series of holes in it and asked to cast six copies. Taylor was also given a specimen of percussion caps and asked to manufacture enough of these to screw into the grenades.

Orsini had designed an advanced weapon: a bomb which would explode on impact, rather than by lighting a fuse. The explosive mixture to be packed inside was fulminate of mercury, a highly volatile sandy-coloured crystalline powder substance. Experiments with the devices took place in Putney (where a hut was blown up), at a disused quarry in Sheffield and in Devonshire, then Orsini took his material to Paris where he met up with three other conspirators.

Now the plot was unveiled: revolutionary logic dictated that with the assassination of Napoleon III France would rise in revolt and in the accompanying international confusion Italy would also rise and would be set free. When Orsini read in the newspapers that Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie were to attend the opera the following evening, it was time for him to call and arm his assortment of co-conspirators.

On January 14th, 1858, as the imperial cavalcade approached, at a sign from Orsini his colleague Gomez threw a bomb. It landed wide, among the imperial horsemen in front of the carriage; Orsini gave the order for the next bomb. There was an explosion, a terrible silence then screams of horror, the sound of falling glass and the whinnying of terrified animals. A policeman ran to the coach to secure the safety of the emperor just as the third bomb, probably thrown by Orsini himself, went underneath, severely wounding the man and ripping his clothes to ribbons.

There were 156 casualties, three people blinded and, though none were killed at the time, eight dying later as a result of the infection of deep wounds in which small particles of bomb and debris had embedded themselves. Orsini had left testing the bombs to his English accomplices and had not observed them in action. In his efforts to gain maximum effect he had packed them too full and the explosions had been too fragmented.

The conspirators were quickly rounded up (one had been apprehended as a suspicious person before the attack). Orsini had been struck on the right temple by a fragment of bomb and was confused; he staggered around amid the carnage and joined a group of people seeking attention for their wounds at a pharmacy, then returned to his lodgings. The police found him there the next day, following the lead of addresses given by those already apprehended.

The Emperor and Empress, relatively unharmed though with slight scratches from flying glass, went on to the opera, stepping past the bodies and through the carnage. Their spirited determination to proceed as normal was universally applauded. It seemed as if all Paris had turned out to see the Emperor on his way back to the palace later that night; far from overthrowing Napoleon III, Orsini’s act had consolidated his popularity. However, the bombing had far-reaching implications for Austria, Italy, France and Britain.

Napoleon III had in his youth been an active supporter of Italian nationalism. The Emperor (nephew of Napoleon I) had spent his youth in exile in the company of other discontented romantics and in Italy had taken part in plots and rebellions. He had come to power by taking advantage of the disruption caused by the 1848 revolution to stand as the candidate for order. He won power in an election that year and consolidated his position in an imperial coup of 1851 after which his government arrested agitators to deport them and he became a hated despot, the enemy of republicanism.

Napoleon III now did two remarkable things which indicated that the attack on his life was not going to propel him further on the path of tyranny: he pointedly refused to see the Austrian ambassador who wished to congratulate him on his escape; and he sent his chief of police, Pierre Marie Petrie, to see Orsini in prison.

Petrie told Orsini to write a letter to the Emperor, which must be a rousing cry to Italian liberation. There has been speculation that the Emperor even penned some of it himself. ‘May your Majesty not reject the words of a patriot on the steps of the scaffold!’ it resounded, ‘Set my country free!’

Napoleon wished to pardon Orsini but, given the death and injury to innocent bystanders, public opinion would not permit it, and the Italian went to a dignified death by guillotine on March 13th, 1858.

Four months later, on July 20th, 1858, Napoleon III met Count Cavour, the prime minister of the independent Italian state of Piedmont, at Plombières. They agreed that Cavour would provoke an uprising in the Carrara-Massa region, the Austrians would certainly intervene, and then the French would respond to drive them from the whole of northern Italy. It was thus that, when Cavour rejected an Austrian ultimatum in April 1859, Napoleon III crossed the Alps with 200,000 men.

While this was by no means a glorious campaign, it secured Lombardy for Piedmont and set in motion the events by which Piedmont took the whole of southern Italy into a united nation; the Papal States and remaining central provinces (except Rome) went over in 1860. The kingdom of Italy was completed with the addition of Venetia in 1866.

In Britain, Prime Minister Palmerston had come under severe pressure from the French foreign minister, Count Walewski, over Britain’s tolerance towards refugees. Some five men living in England had helped with the plot, only one ever stood trial: Dr Simon Bernard, a French radical who had been involved in purchasing material for the bombs and in having them tested. He was found not guilty at the Old Bailey on a specimen charge of the murder of a sergeant of the Paris Civil Guard in the bomb attack. The recruitment of assassins and the construction of bombs in Britain were to go unpunished.

Palmerston introduced a Conspiracy to Murder Bill in 1858 to make plotting the assassination of foreign rulers a felony. The Bill passed its first reading easily, despite trenchant criticism from radicals who were angry about interference with the freedom of refugees. Such concerns, combined with anti-French feeling, resulted in an ambush of Palmerston at the second reading of the Bill when he foolishly lost his temper, shaking his fist at radical critics. The conservatives joined forces with the radicals to defeat him, and Palmerston’s government fell.

Orsini’s case highlights issues which are still vexing democracies in dealing with foreign activists. Britain has maintained a precarious balance between support for persecuted refugees from despotic regimes, and a respect for life which the same liberal principles insist should extend even to the life of a dictator in control of a police state.

A further conundrum, for those who eschew political violence, is that Orsini’s act of what would come to be called terrorism seems to have worked: it was the direct cause of Italian liberty. The lesson of the single, violent act to spark a revolutionary conflagration was taken up by future generations, including the People’s Will (who assassinated Tsar Alexander II), Gavrilo Princip, and Al-Qaeda.

The answer to the apparent success of Orsini’s plot lies with the complex nature of Napoleon III who was for the whole of his life a romantic revolutionary, more fond of the grand gesture than detailed policy manipulation. He had long supported Italian freedom, and took the opportunity of the attack on his life to take the Italian cause further while striking a blow against Austria. It was the combination of Napoleon’s character with the precise political balance of the times that led to his taking opportunistic advantage of the attention the attack attracted to him. It was a rare, perhaps unique, instance of the victim of an outrage furthering the cause of its perpetrator.

Jad Adams’ Hideous Absinthe, on cultural relations between Britain and France in the 19th century, will be published by I.B.Tauris in 2004.