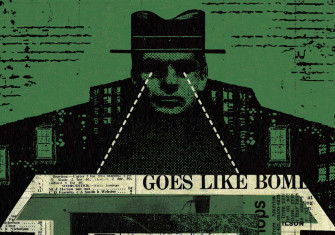

Revolution in the air

Those who control the media control the state. Lenin knew this, but by 1991 his Soviet successors had forgotten, to their ultimate cost.

This is a time of battles between international media organisations and national governments. Think of the decision by the BBC’s China correspondent, John Sudworth, to move to Taiwan after ‘threats’ and ‘increased surveillance and harassment’ because of his reporting of Beijing’s treatment of the Uighurs, or Russia designating Radio Free Europe as ‘foreign agents’. Political elites seeking to establish and increase global influence place great emphasis on how their stories are told. To understand why it is worth considering the very different ways in which the world came to know about the end of imperial Russia and the eventual collapse of the Soviet regime that replaced it.

Thirty years ago, in August 1991, a group of hardline Communists seized power in Moscow. Their aim was to save the Soviet system as they knew it. They did not follow the plans of their Bolshevik forbears when it came to controlling the coverage of their coup. Their failure to do so betrayed a lack of planning that helps to explain why their time at the summit of Soviet power lasted a mere three days.