A History of Pizza

The world’s most popular fast food has ancient roots, but it was a royal seal of approval in 1889 that set pizza on the path to global domination.

Pizza is the world’s favourite fast food. We eat it everywhere – at home, in restaurants, on street corners. Some three billion pizzas are sold each year in the United States alone, an average of 46 slices per person. But the story of how the humble pizza came to enjoy such global dominance reveals much about the history of migration, economics and technological change.

People have been eating pizza, in one form or another, for centuries. As far back as antiquity, pieces of flatbread, topped with savouries, served as a simple and tasty meal for those who could not afford plates, or who were on the go. These early pizzas appear in Virgil’s Aeneid. Shortly after arriving in Latium, Aeneas and his crew sat down beneath a tree and laid out ‘thin wheaten cakes as platters for their meal’. They then scattered them with mushrooms and herbs they had found in the woods and guzzled them down, crust and all, prompting Aeneas’ son Ascanius to exclaim: “Look! We’ve even eaten our plates!”

Pizza for breakfast

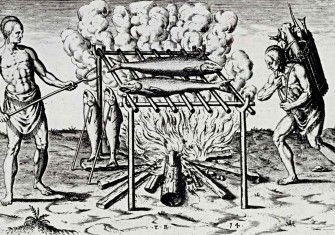

But it was in late 18th-century Naples that the pizza as we now know it came into being. Under the Bourbon kings, Naples had become one of the largest cities in Europe – and it was growing fast. Fuelled by overseas trade and a steady influx of peasants from the countryside, its population ballooned from 200,000 in 1700 to 399,000 in 1748. As the urban economy struggled to keep pace, an ever greater number of the city’s inhabitants fell into poverty. The most abject of these were known as lazzaroni, because their ragged appearance resembled that of Lazarus. Numbering around 50,000 they scraped by on the pittance they earned as porters, messengers or casual labourers. Always rushing about in search of work, they needed food that was cheap and easy to eat. Pizzas met this need. Sold not in shops, but by street vendors carrying huge boxes under their arms, they would be cut to meet the customer’s budget or appetite. As Alexandre Dumas noted in Le Corricolo (1843), a two liard slice would make a good breakfast, while two sous would buy a pizza large enough for a whole family. None of them were terribly complicated. Though similar in some respects to Virgil’s flatbreads, they were now defined by inexpensive, easy-to-find ingredients with plenty of flavour. The simplest were topped with nothing more than garlic, lard and salt. But others included caciocavallo (a cheese made from horse’s milk), cecenielli (whitebait) or basil. Some even had tomatoes on top. Only recently introduced from the Americas, these were still a curiosity, looked down upon by contemporary gourmets. But it was their unpopularity – and hence their low price – that made them attractive.

For a long time, pizzas were scorned by food writers. Associated with the crushing poverty of the lazzaroni, they were frequently denigrated as ‘disgusting’, especially by foreign visitors. In 1831, Samuel Morse – inventor of the telegraph – described pizza as a ‘species of the most nauseating cake … covered over with slices of pomodoro or tomatoes, and sprinkled with little fish and black pepper and I know not what other ingredients, it altogether looks like a piece of bread that has been taken reeking out of the sewer’.

When the first cookbooks appeared in the late 19th century, they pointedly ignored pizza. Even those dedicated to Neapolitan cuisine disdained to mention it – despite the fact that the gradual improvement in the lazzaroni’s status had prompted the appearance of the first pizza restaurants.

Royal approval

All that changed after Italian unification. While on a visit to Naples in 1889, King Umberto I and Queen Margherita grew tired of the complicated French dishes they were served for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Hastily summoned to prepare some local specialities for the queen, the pizzaiolo Raffaele Esposito cooked three sorts of pizza: one with lard, caciocavallo and basil; another with cecenielli; and a third with tomatoes, mozzarella and basil. The queen was delighted. Her favourite – the last of the three – was christened pizza margherita in her honour.

This signalled an important shift. Margherita’s seal of approval not only elevated the pizza from being a food fit only for lazzaroni to being something a royal family could enjoy, but also transformed pizza from a local into a truly national dish. It introduced the notion that pizza was a genuinely Italian food – akin to pasta and polenta.

Nevertheless, pizza was slow to move out of Naples. The initial spur was provided by migration. From the 1930s onwards, a growing number of Neapolitans moved northwards in search of work, taking their cuisine with them. This trend was accelerated by war. When Allied soldiers invaded Italy in 1943-4, they were so taken with the pizza they encountered in Campania that they asked for it wherever else they went. But it was tourism – facilitated by the declining cost of travel in the postwar period – that really consolidated pizza’s position as a truly Italian dish. As tourists became increasingly curious about Italian food, restaurants throughout the peninsula started offering more regional specialities – including pizza. The quality was, at first, variable – not every restaurant had a pizza oven. Nevertheless, pizza quickly spread throughout Italy. As it did so, new ingredients were introduced in response to local tastes and the higher prices that customers were now willing to pay.

Pizza goes west

But it was in America that pizza found its second home. By the end of the 19th century, Italian emigrants had already reached the East Coast; and in 1905, the first pizzeria – Lombardi’s – was opened in New York City. Soon, pizza became an American institution. Spreading across the country in step with the growing pace of urbanisation, it was quickly taken up by enterprising restaurateurs (who were often not from an Italian background) and adapted to reflect local tastes, identities and needs. Shortly after the US entered the Second World War, a Texan named Ike Sewell attempted to attract new customers to his newly opened Chicago pizzeria by offering a much ‘heartier’ version of the dish, complete with a deeper, thicker crust and richer, more abundant toppings – usually with cheese at the bottom and a mountain of chunky tomato sauce heaped on top of it. At about the same time, the Rocky Mountain Pie was developed in Colorado. Although not as deep as its Chicago relative, it had a much wider crust, which was meant to be eaten with honey as a desert. In time, these were even joined by a Hawaiian version, topped with ham and pineapple – much to the bewilderment of Neapolitans.

From the 1950s onwards, the rapid pace of economic and technological change in the US transformed the pizza even more radically. Two changes are worthy of note. The first was the ‘domestication’ of pizza. As disposable incomes grew, fridges and freezers became increasingly common and demand for ‘convenience’ foods grew – prompting the development of the frozen pizza. Designed to be taken home and cooked at will, this required changes to be made to the recipe. Instead of being scattered with generous slices of tomato, the base was now smothered with a smooth tomato paste, which served to prevent the dough from drying out during oven cooking; and new cheeses had to be developed to withstand freezing. The second change was the ‘commercialisation’ of pizza. With the growing availability of cars and motorcycles, it became possible to deliver freshly cooked food to customers’ doors – and pizza was among the first dishes to be served up. In 1960, Tom and James Monaghan founded ‘Dominik’s’ in Michigan and, after winning a reputation for speedy delivery, took their company – which they renamed ‘Domino’s’ – nationwide. They and their competitors expanded abroad, so that now there is scarcely a city in the world where they cannot be found.

Paradoxically, the effect of these changes was to make pizza both more standardised and more susceptible to variation. While the form – a dough base, topped with thin layers of tomato and cheese – became more firmly entrenched, the need to appeal to customers’ desire for novelty led to ever more elaborate varieties being offered, so that now Pizza Hut in Poland sells a spicy ‘Indian’ version and Domino’s in Japan has developed an ‘Elvis’ pizza, with just about everything on it.

Today’s pizzas are far removed from those of the lazzaroni; and many pizza purists – especially in Naples – balk at some of the more outlandish toppings that are now on offer. But pizza is still recognisable as pizza and centuries of social, economic and technological change are baked into every slice.

Alexander Lee is a fellow in the Centre for the Study of the Renaissance at the University of Warwick. His latest book, Humanism and Empire: The Imperial Ideal in Fourteenth-Century Italy is published by OUP.