The Sons of Mars

The struggle for control of the straits dividing Sicily from southern Italy brought the two great empires of the Mediterranean, Carthage and Rome, head to head. It was a world in which ruthless mercenaries prospered.

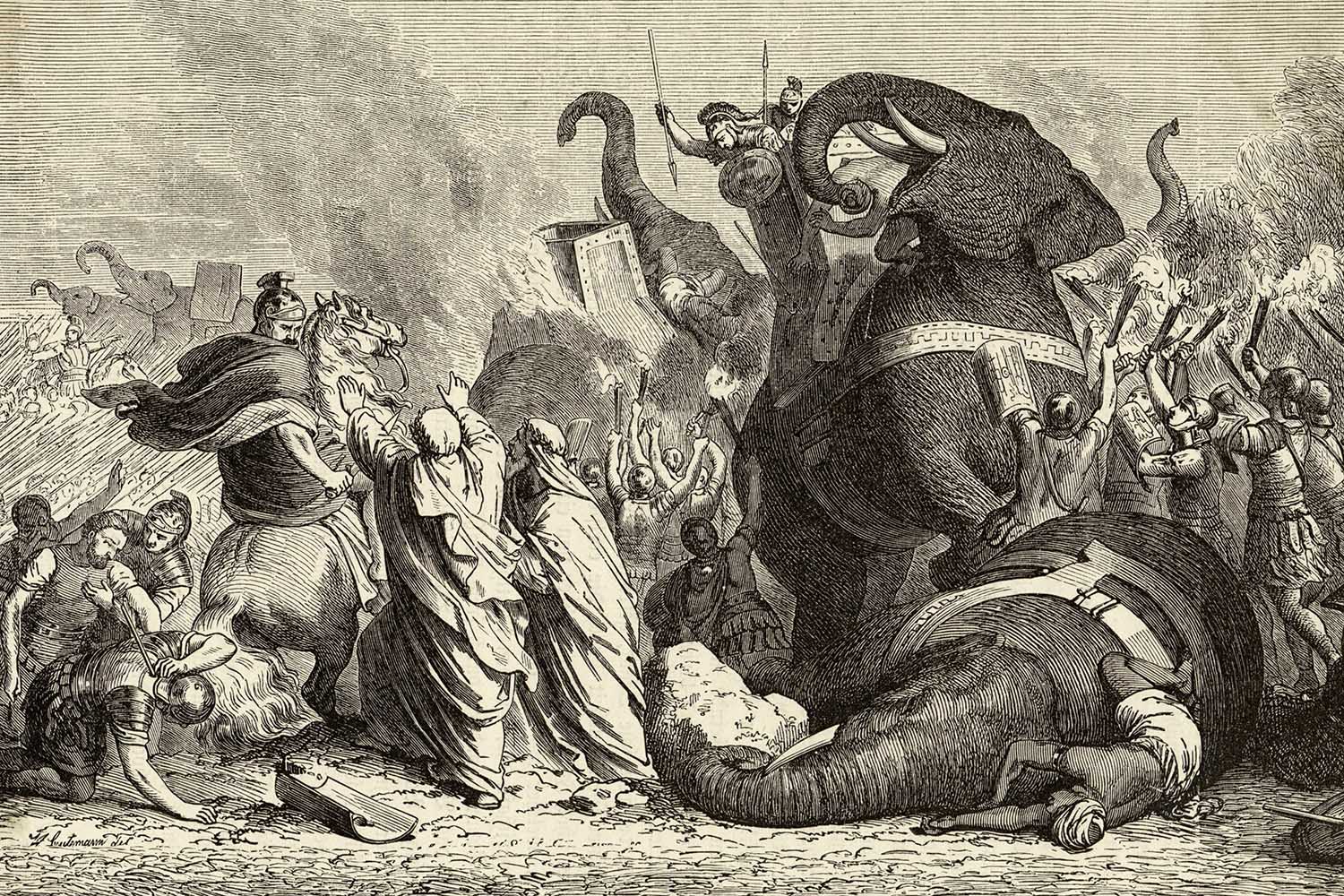

Pyrrhus abandons his fight in Tarentum against the Romans to aid the Sicilian Greeks, 19th-century engraving. Mary Evans Picture Library.

Hiero II, the ruling general of the Greek city-state of Syracuse, led a campaign in 265 BC north towards a coastal Sicilian city, Messana, held by a group of Campanian mercenaries known as the Mamertines. The Campanians were part of a vast Oscan tribal group originally from the Apennine mountains, who had now settled in the southern Italian region of Campania. By the end of the fifth century BC the hill tribes had invaded the nearby plains, displacing the Etruscan and Greek inhabitants of the region, taking control of nearly all of the land between Salerno and Cumae. As the decades passed, the mountain dwellers gradually let go of their old way of life and adopted the civic lifestyle of the people they had conquered. The newly sedentary Campanians appealed to the Romans for their help against their aggressive neighbours, the Samnites. In 343 BC Rome came to their aid and, in turn, the Campanians became subjects of the Republic. From then on the Campanians were considered civites sine suffragio, meaning they had all of the privileges of Roman citizens but without the right to vote in Rome.

Regardless of their new status as subjects under Roman hegemony, the Campanians, and in particular the Mamertines, never relinquished their martial skills. In fact, the two major powers in Sicily, the Carthaginians and the island’s Greek city-states, had relied on southern Italy as a plentiful source of mercenaries ever since the Oscan peoples seized the Campanian plain. They continued to do so in the centuries that followed, as they continuously fought each other over domination of the island. For decades, the foreign soldiers had raided and pillaged the entire region both by land and sea. As the ruler of the most powerful city of eastern Sicily, Syracuse, Hiero II would not tolerate the mercenaries any longer and, by the middle of the third century, had the necessary resources to end their constant piracy. When he confronted the Mamertines near the River Longanus, his forces crushed them. The few surviving Mamertines fled to safety and debated what to do next. The fear of future attacks had caused so much panic that they turned to the most powerful empire of the western Mediterranean, Carthage, as well as the Roman Republic to save them from Hiero.

In doing so, the Mamertines sparked one of the most significant wars of the ancient Mediterranean, the First Punic War (264-241 BC), becoming some of the most notorious and renowned mercenaries of the classical world.

Near the end of the fourth century BC, Agathocles, the new tyrant of Syracuse and a Sicilian warlord, had recruited a substantial number of Campanian mercenaries. From the moment Agathocles had seized power in 317 BC, the former soldier had employed mercenaries and continued to do so throughout his entire reign, as he established a powerful empire in eastern Sicily. As Agathocles warred with the Carthaginians and rival Greek city-states to take control of the entire eastern half of the island, he had added the city of Messana to his possessions some time between 315 and 312 BC.

When Agathocles was 72, in 289 BC, the self-proclaimed king of Syracuse and Sicily was assassinated by members of his own family, following arguments surrounding his succession. After his death, the large group of Campanian mercenaries he had hired clashed with the Syracusan citizenry. To convince the Italian soldiers to leave, the Syracusans offered them the conquered city of Messana, which they quickly accepted. A year later, in 288 BC, the citizens of Messana allowed the mercenaries to enter their city only to regret their decision shortly after. Once inside, the foreign troops slaughtered the men, enslaved the women and seized the city. From then on, the mercenaries called themselves the Mamertines, or ‘the sons of Mamers’, the name for the war-god Mars in the Oscan language of the Campanians.

Due to the near constant influx of Campanian mercenaries into Sicily for over a century, this was not the first time that foreign soldiers had seized a city on the island. For instance, Campanians took the western Sicilian city of Entella in 404 BC. However, the degree to which the Mamertines devoted themselves to violence and warfare, as they either intimidated their neighbours into giving them tribute or took their possessions by force, quickly made them notorious throughout the region. By the end of the third century BC, the self-styled ‘Sons of Mars’ had sacked and pillaged as far as Gela and Camarina along the southern coast of Sicily.

While the Sons of Mars were a terrible irritation, many of the Greek city-states of Sicily still considered the Carthaginian Empire as their main threat, especially the people of Syracuse. Therefore, after a large Carthaginian army had besieged the city once again, Syracuse and the Hellenistic community of Sicily chose a new champion to defend them: King Pyrrhus of Epirus. At the time, the general was fighting a war with the Romans on behalf of a Greek city in southern Italy, Tarentum. Even though he had achieved two victories over the armies of the Republic, the loss of his soldiers had been so great that the ambitious king decided to abandon the Tarentines and heed the call of the Sicilian Greeks, believing that the Carthaginians would be an easier foe to overcome.

Pyrrhus arrived in Sicily in 278 BC and began his conquest of the island. However, only two years later, he had failed to accomplish this goal, as he could not capture the formidable Carthaginian stronghold of Lilybaeum. His failure was mostly due to the fact that the Sicilian Greeks had turned against him for his increasingly autocratic conduct towards them. Throughout Pyrrhus’ Sicilian campaign, the Mamertines had been allied with the Carthaginians against the Hellenistic general. So, even though the king of Epirus attacked and defeated the mercenaries, the Sons of Mars managed to retain Messana and their independence. When the Greeks of Sicily had completely risen against their denounced, prior saviour, many of them even wanted the Carthaginians or the Mamertines to then save them from Pyrrhus. The aspiring king of Sicily withdrew from the island in the autumn of 276 BC and returned to Italy to fight Rome for Tarentum once again. Pyrrhus lost the Battle of Benevento in 275 BC, putting an end to all of his campaigns west of Epirus. This final withdrawal from Italy of the Hellenistic commander greatly benefited the Romans, who were then free to conquer Tarentum in 272 BC, along with the rest of the Italian south, previously controlled by the Greeks.

While the Romans were preoccupied with Pyrrhus and Tarentum, they were unable to deal with a volatile situation for which they were partly to blame concerning the actions of another group of dangerous Campanian soldiers. When Pyrrhus invaded Italy for Tarentum, the citizens of Rhegium panicked and, because of their alliance with the Roman Republic, immediately called for Rome to send sufficient aid for a proper defence of the city. For its strategic location on the south-western tip of Italy, with only the narrow Straits of Messana separating it from Sicily, Rhegium was a pivotal ally and the Romans quickly obliged.

Under the command of an officer named Decius, the Romans sent a garrison of 4,000 Campanian soldiers to the city. Just as the Sons of Mars had done a decade before, these Campanian troops also attacked the citizenry after the city gates were opened freely to them. But this time the Campanians did not massacre all of the male citizens; those who were not killed were instead forced into exile. Furious over their soldiers’ treatment of one of their allies, the Republic took action. After the capture of Tarentum, Roman soldiers besieged Rhegium in 271 BC. A year later, the Roman army broke through the city’s defences and the remaining 300 Campanians left alive were taken captive. In the heart of the capital, the Roman Forum, the treasonous soldiers were flogged and decapitated.

With the threat of Pyrrhus gone, the mercenaries returned to marauding. The Sons of Mars managed to conquer a substantial portion of north-eastern Sicily, creating an empire whose territory stretched from Mount Etna in the south and as far west as Halaesa on the north coast. The foreign pirates had now become too great a threat for Syracuse to ignore. After the next tyrant took control of the city and reorganised the army to include a new native militia force alongside the conventional contingent of mercenaries, a truce was established with the Carthaginian Empire to deal with the Mamertines. Hiero II was one of the most loyal supporters of Pyrrhus within Syracuse and managed to retain his high position in the city even after the king had retreated from the island. At first, his position in the city was limited for he was only acknowledged as Strategus, the overall commander of the army. It was only after the general confronted the Mamertines for the first time at the victorious battle of the River Cyamosorus in 269 BC, that he was able to secure complete control of Syracuse and, the following year, take the title of Strategus Autocrator.

As an autocratic ruler with full powers, Hiero primarily focused on stabilising the city in the anarchic period following the assassination of Agathocles. The tyrant was then free to focus on striking his fatal blow against the Mamertines. With fewer than 12,000 soldiers, Hiero invaded north-eastern Sicily in 265 BC. As the campaign progressed a stalemate ensued. The Sons of Mars were unable to drive off the invaders competely and Hiero could not definitively defeat them either. Then in the spring of 264 BC the two forces met on the plains of Mylae near the River Longanus. On the battlefield the blessing of the war god was kept from his devoted followers and bestowed instead on their enemies, as Hiero’s Syracusan army annihilated the Sons of Mars.

Among the remnants of the Mamertine army, a fierce debate began over whether or not they should send appeals for help to either Carthage or Rome. The Carthaginian Empire had been a faithful ally during the years of Pyrrhus’ Sicilian campaign, but the link between the mercenaries and the Roman Republic had grown stronger. As Campanians, not only were the Mamertines fellow Italians but they were also still technically non-voting Roman citizens. In the end, the two factions were unable to agree on one ally so they sent a plea for help to both of them. Sending appeals to both states may also have been a logical decision for the Mamertines, since the Romans and Carthaginians had been allies for centuries, with the first of three treaties between the two agreed at the founding of the Republic in 508-7 BC. The most recent alliance was formed in 279-8 BC, forged of the mutual hostility they felt towards Pyrrhus and the various Hellenistic city-states of southern Italy and Sicily. Although the Romans never aided the Carthaginians against Pyrrhus in Sicily, the agreement between both of them meant that the Romans were allowed to conquer the Magna Graecia region of southern Italy without any intervention from Carthage.

The Carthaginians answered the call immediately and sent troops. Carthage was much more content with Messana being occupied by themselves or the Mamertines than with it being controlled by Syracuse once again, so the decision was an easy one. Carthaginian ships harboured at the Aeolian Islands were so close to Messana that they were able to place a garrison within the city before Hiero reached its defensive walls. Unwilling to assault the Carthaginians, Hiero led his army back to Syracuse. Upon his return the citizenry rewarded him for his crushing victory over the Mamertines at the battle of the River Longanus by proclaiming him as their king, even though he had ultimately failed in finishing the mercenary pirates off.

After the Mamertine embassy addressed the Roman Senate to plead their case, by the middle of May the Romans were well aware of the Carthaginian garrison already stationed in Messana. The ruling body of the Republic was much less decisive than its alleged allies, taking over a month before a resolution was reached. The majority of the senators wanted to aid the Campanian mercenaries but not because of the need to help fellow Italians. To many Romans, war with Carthage was not only a necessary step to nullify a future threat; it was also a very profitable prospect.

The Carthaginian Empire was the most powerful in the western Mediterranean, mostly due to the wealth it had amassed through its dominance of trade in the region and the strength of its navy. With its powerful fleet, Carthage had already conquered much of North Africa, portions of Spain, mostly along the southern and eastern coasts, as well as Sardinia and the smaller islands of the region. Since the Romans had conquered the southern part of the Italian peninsula, the Carthaginian occupation of Messana meant that the imposing empire was then right on their border with only a narrow stretch of sea separating the two states across the straits. The Carthaginians only needed to subdue Syracuse to control all of Sicily, giving them the ideal base from which to launch an invasion of southern Italy. Yet the armies of the Republic had proven that Rome was not weak and vulnerable: quite the opposite. The Romans had just extended their hegemony over the entire Italian peninsula, so even though Carthage was viewed as a threat it was one that the people of Rome were confident of overcoming; victory would be lucrative.

On the other hand, an influential group of Roman senators, comprised of ex-consuls and other leading politicians, rejected the motion for war. The most obvious reason was the blatant hypocrisy of aiding the Mamertines when the Romans had just executed their Campanian kinsmen for the seizure of Rhegium in the same way as the Sons of Mars had taken Messana. Furthermore, war in general did not always end in victory and these powerful individuals may have felt that the overconfidence of many senators might lead to the ruin of the Republic. Carthage had long been an ally and had shown no signs of hostility or aggression; and, as an enemy, it would be an extremely dangerous adversary. Initially, the smaller faction prevailed, for the Roman Senate did not ratify the motion to send aid to the Sons of Mars. However, the war hawks of the Senate would not give in so easily.

The most prominent politician to support the war was one of the Roman consuls, Appius Claudius Caudex. Like most consuls of the Roman Republic, Claudius wanted to lead a glorious campaign during his consulship to raise his, and his family’s, prestige. So the opportunity to become the first Roman general to lead the legions beyond the confines of the Italian peninsula was too great to pass up. Claudius brought the motion before an assembly of the people, most likely the Comitia Centuriata, which included many of the wealthiest members of the population. It took very little to convince these merchants of the equestrian class, for they would profit greatly from government contracts providing military supplies or by taking part in the lucrative slave industry bolstered by numerous prisoners of war. Thus, with the people voting in favour, the Senate announced a formal declaration of war in late June, with Claudius in command of the troops sent to aid the Sons of Mars. By late August, Claudius had raised his roughly 20,000-strong consular army, consisting of two legions with contingents of Italian auxiliaries, and gathered a small fleet of triremes and transports from Tarentum, Naples, Elea and Locri and reached Rhegium.

Once the Mamertine embassy returned to Messana to report what the Romans had decided, the Sons of Mars adopted their new allies’ fresh aggression towards the Carthaginians and expelled their entire garrison within the city. Carthage was outraged over the treatment of its soldiers; so much so that they crucified the commander of the garrison for allowing it to happen. Carthage immediately besieged Messana with its army, blockaded the port with its navy and sent ships to Cape Pelorias to keep watch over the straits between Messana and the Romans at Rhegium in southern Italy. The Carthaginians also brought Hiero and his Syracusan army back into the fray, for a new alliance was made between the two former enemies to prevent the intervention of the Romans into the affairs of Sicily. The fact that Syracuse and Carthage were able so quickly to set aside a centuries-long feud shows how threatened the two were by the Romans.

With both of the major powers of the island poised against him, Claudius desperately needed to reach the Mamertines but was thwarted in his attempt to cross the straits with his army by the powerful Carthaginian navy. Yet fortune was on the Roman consul’s side, for he not only eventually managed to make the crossing at night, but the Romans also were able to secure the capture of an overly ambitious Carthaginian vessel that had ran aground in its attempts to attack the Roman ships. For a rising power in the Mediterranean that lacked a navy, the vessel was an incredibly valuable prize that later served as a blueprint for the ships of the Roman fleet that was created a few years later.

Shortly after the Romans had reached Messana, Hiero combined his Syracusan forces with the Carthaginians besieging the city. At first, Claudius attempted to resolve the conflict with diplomacy. The consul appealed to both sides stating that his only desire was to protect his new allies from further aggression. If both of the armies of Carthage and Syracuse put an end to their assaults on the Sons of Mars, Claudius promised to withdraw to the Italian mainland. Understandably, neither of the Sicilian powers fell for the ploy. Not only did they accuse the Romans of acting in their own interests to exploit the situation, but they also refused to let the treacherous pirates get off so easily. Since both the Carthaginians and Syracusans had over 10,000 soldiers each, Claudius knew he could overwhelm one of them, but would be outnumbered if they combined forces. Thus, realising the futility of negotiations, the consul took the initiative and assaulted the Syracusan camp, leaving a small force augmented by the Mamertines in the north to prevent Carthage from intervening.

In response, Hiero mustered his army and ordered his cavalry to attack the small force of horsemen the Romans had brought across the sea. The vastly superior Syracusan cavalry successfully drove off their Roman counterpart but were not so lucky against the legionaries. Unable to break through the enemy lines with his cavalry, Hiero watched as the Roman infantry crushed his own hoplites (citizen-soldiers), forcing the king to retreat with the remainder of his army back to Syracuse, from where he later pleaded for peace with Rome in 263 BC.

With Hiero gone, Claudius was free to attack the camp of the Carthaginian commander Hanno with the help of the Sons of Mars. At first, Hanno managed to drive the Roman army out and advanced on the battered Italians. Yet the relentless forces of Rome eventually pushed the Carthaginians back behind their defences and defeated them. As Roman allies, the Sons of Mars were secure in their captured city, but after the First Punic War they could no longer act as pirates and faded from history. However, for their pivotal role in the beginning of the great wars with Carthage, the legend of the Mamertines lived on in Rome and morphed over the centuries. By the Augustan age, in the first century BC, Roman propaganda held that the Sons of Mars had aided the citizens of Messana to receive land as a reward, instead of taking the city by force. Ultimately, popular folklore has failed to eradicate the behaviour of the notorious mercenaries from the historical record and the true nature of the Sons of Mars has prevailed.

Erich B. Anderson is an historian specialising in warfare of the ancient and medieval world. This article originally appeared in the March 2015 issue of History Today with the title 'The Rise of the Sons of Mars'.