Victims of Their Own Success

The United States should heed the lessons of 1,000 years ago, if it is to sustain its military superiority.

The picture is a familiar one. Young men, spurred on by religious beliefs and encouraged by their peers, gathered on the edges of Asia Minor, waiting to attack the Christian world to the west. Immense kudos was to be won within the Muslim world from inflicting pain and damage on innocent victims: men, women and children who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Launching attacks could and did cause untold damage to the economy, driving fear and changing the way people lived, moved and thought. Training bases in northern Syria prepared eager would-be soldiers, teaching them the survival techniques needed to infiltrate enemy territory and, of course, how to launch their attacks. And spiritual rewards were on offer too: a place in paradise, if you met your end during the mission. That was Asia Minor 11 centuries ago.

The picture is a familiar one. Young men, spurred on by religious beliefs and encouraged by their peers, gathered on the edges of Asia Minor, waiting to attack the Christian world to the west. Immense kudos was to be won within the Muslim world from inflicting pain and damage on innocent victims: men, women and children who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. Launching attacks could and did cause untold damage to the economy, driving fear and changing the way people lived, moved and thought. Training bases in northern Syria prepared eager would-be soldiers, teaching them the survival techniques needed to infiltrate enemy territory and, of course, how to launch their attacks. And spiritual rewards were on offer too: a place in paradise, if you met your end during the mission. That was Asia Minor 11 centuries ago.

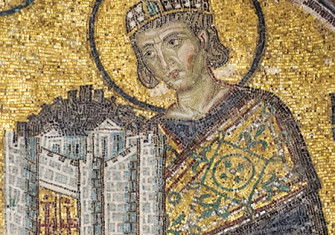

The Roman Empire splintered in two spectacular explosions. First, Rome itself was sacked in 410 and then its western provinces and many of those of North Africa collapsed later in the fifth century. Two hundred years later, ‘the most important parts of the Empire’ did not just remain standing, but were flourishing. Centred on the great city of Constantinople, the East Roman (or Byzantine) Empire, controlled the wealthy grain basket of the Nile delta, as well as Anatolia (modern Turkey), much of the Balkans, Greece, Palestine and Syria. Life looked rosy, as the numismatic and archaeological records show.

The second expansion brought the Byzantine Empire to its knees as followers of the Prophet Muhammad poured out of the Arabian peninsula in the 630s, forging a vast new world that linked Spain with the Middle East and Central Asia, pushing right up to the border with China by 751. The Empire hung on for dear life, pouring resources into a frontier network across Asia Minor to hold back the tide.

Byzantine generals were realistic about how secure the border could be: there was no hope of stopping bands of motivated, fast-moving individuals from penetrating under the cover of darkness or otherwise: policing a frontier in this way required (and still requires) money, time, resources and people to maintain it. Instead, the Byzantines had to learn how to deal with attacks.

They identified patterns. Timing was predictable; so, too, were the targets: the attackers were more keen on glory than death, on the bragging rights in this world than the next and more keen on enriching themselves than finding out what paradise had to offer. The best approach was to adapt to the reality and prepare for regular pin-pricks, rather than becoming the target of more powerful forces further away. As seen from Constantinople, there would always be problems on the periphery, so it was important to build relations with Baghdad and Cairo and to use official channels to try to rein in troublesome warlords in border zones, whose successes could destabilise not just the Byzantine Empire but the Abbasid Caliphate, too.

In the 10th century, however, the balance began to change. A series of economic shocks rattled the economies of the Middle East and Central Asia, in part the result of a period of climate change. Soul searching in Baghdad opened the door for daring Byzantine raids that knocked out the attack bases that had been used to such great effect for almost 200 years. That, in turn, changed the make-up and fighting practices of the imperial military. Having pioneered defensive tactics to prevent raids causing too much damage, attention now turned to big targets: fortified towns and cities.

Within the space of a generation, the Byzantines had rolled the frontier back hundreds of miles, recovering places long lost to Muslims. The jewel in the crown was Antioch in northern Syria, the gateway to Palestine, but also the protecting valve to defend Asia Minor and the interior. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the century that followed saw an astonishing period of economic and demographic growth, as well as an intellectual and cultural flowering, as artists, scholars and writers like Michael Psellos created some of the treasures of Byzantine culture.

The problem was that when a new threat appeared in the form of the Sekjuk Turks in the 11th century, it took the Byzantines too long to remember how to fight a rearguard action. Instead of dealing swiftly with nimble attackers, a ploy that had worked in the past, the response was to send large, heavy armies that took too long to move and were left chasing shadows.

A similar problem, it seems, is facing the US Air Force today. In a recently published report, Lt General David Barno, former Commander of Military Operations in Afghanistan, argued that the USAF – like the Byzantine army of the 10th and 11th centuries – is a victim of its own success. Not a single American warplane has been shot down by an enemy aircraft since 1991; and not one has been lost to enemy air defences since 2003. ‘As a result’, General Bardo notes, ‘the risk to aircraft and airmen in combat has become nearly negligible’.

At a time when the US is acutely aware of growing ambition and military expenditure by China and Russia, the fact that pilots have never experienced ‘contested air war’ means that investment is needed to prepare for threats of the future and not those of the present. It also means that skills need to be taught and developed in advance, rather than when it is too late. ‘Resilience’, for example, to enable soldiers and airmen to cope when ‘more and more squadrons of their mates don’t come home’, should be impressed on serving a military that has got used to undisputed superiority.

When the going had been good in Constantinople 1,000 years ago, there were voices like those of General Barno, too, who warned about under-funding in the armed forces and the fact that young people did not want to serve the emperor but to feather their own nests by becoming lawyers and making money. By the time anyone listened, it was too late. Whether General Barno’s warning meets the same deaf ears remains to be seen.

Peter Frankopan’s The Silk Roads: A New History of the World is published by Bloomsbury (UK) and Knopf (US).