God Gave Rock and Roll to You

Fiery, energetic and preached by charismatic frontmen, Pentecostal Christianity had a big influence on rock and roll in its formative years. Many early stars had religious upbringings, inspiring their personas, music – and fears of eternal damnation.

Services at the Pentecostal Church of God, Lejunior, Harlan County, Kentucky, 15 September 1946.

The television preacher Jimmy Swaggart became a Christian megastar in the 1980s broadcasting from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. His popular crusades and regular services appeared on television sets across the United States and around the world. At its peak, his ministry was taking in over one million dollars a week. He had honed a brash, bold, loud style of preaching that made him a revered figure, both in the context of the Assemblies of God – a group of affiliated churches that formed the world’s largest Pentecostal denomination – and in the broader world of evangelicalism. Critics reviled his holier-than-thou pulpit posturing and his bellicosity. Some stations even took him off the air for his religious and cultural bigotry.

Like many other Pentecostal preachers – who were moving into politics at a rapid rate – Swaggart believed that the Holy Ghost emboldened him to witness the arrow-straight truths of the Bible. With his southern drawl, he thundered against Hollywood celebrities, evolutionary scientists, communists, homosexuals, Catholics, feminists, secular liberals and other ‘enemies’ of the faith. Americans had lost interest in the Bible, he warned with deadly seriousness. A reporter at the New York Times took note. The Reagan-era televangelist was ‘tapping some powerful resentments here; he is speaking to the disenfranchised’. The country rightly deserved God’s judgment, Swaggart assured his audience with fury.

In the summer of 1985, Swaggart was on the road, conducting one of his mass revival crusades in New Haven, Connecticut. Before the cameras and the glare of stage lights he paced back and forth, waving his arms like he was fending off a swarm of bees. He raised his Bible high above his head. He shouted at his audience about the moral degeneracy that dragged reprobates through the gates of hell. At one performance, he took aim at ‘the devil’s music’: rock and roll.

How had Christians made peace with this vile, hideous music, he asked with urgency in his voice, drawing out words like ‘pul-pit’ and ‘bye-bull’. The issue was a personal one for him, he confided, pausing for emphasis and lowering his voice before lunging at the crowd, finger pointed upward to drive home his jeremiad.

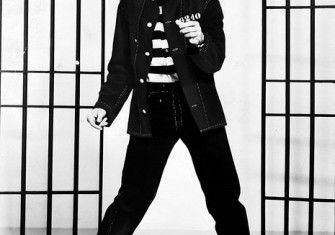

‘My family started rock and roll!’ he exclaimed in front of the silent assembly of thousands. ‘I don’t say that with any glee! I don’t say it with any pomp or pride! I say it with shame and sadness, because I’ve seen the death and the destruction. I’ve seen the unmitigated misery and the pain. I’ve seen it!’ His voice cracking with emotion, he railed: ‘I speak of experience. My family – Jerry Lee Lewis, with Elvis Presley, with Chuck Berry … started rock and roll!’ His claim served an obvious rhetorical point, but there was also much truth to it.

Indeed, Pentecostalism – the fast-growing apocalyptic religion of spiritual abundance, speaking in tongues, healing and musical innovation – inspired many first generation rock and rollers. Jerry Lee Lewis, Swaggart’s cousin, along with Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Little Richard, B.B. King and others were all raised in or regularly attended Pentecostal services in their formative youth. Rock and roll – the soundtrack of rebellion and the music of side-burned delinquents and teenage consumers – owed a surprising debt to Holy Ghost religion. It is true that Pentecostalism formed just one of the tributaries that fed the raging river of rock and roll, but the importance of the spirit-filled faith to the new hybrid genre was significant.

Growing up in the Assemblies of God church, Jerry Lee Lewis and Jimmy Lee Swaggart were close. In fact, they were like brothers. They bonded over music and their shared Pentecostal experience. What they both lacked in formal education, they more than made up for in stage presence, style and charisma.

Jerry Lee’s aunt and Jimmy Lee’s grandmother, Ada, liked to tell family, friends, and anyone who would listen about the Holy Ghost baptism she experienced at a camp meeting in Snake Ridge, Louisiana. ‘You’ve got to get it’ she implored. ‘You’ve got to have it. You really don’t know the Lord like you should until you receive it.’ When the power of the almighty struck her, she said, ‘the presence of God became so real’. Suddenly ‘it seemed as if I had been struck by a bolt of lightning. Lying flat on my back, I raised my hands to praise the Lord. No English came out. Only unknown tongues.’

The ‘Godfather of Soul’ James Brown could also reflect on a religious youth. Brown spent his at the United House of Prayer church in Augusta, Georgia. Its flashy leader, Sweet Daddy Grace, wore a cape and was ‘like a god on earth’. When Grace died in 1960, Ebony magazine called him a ‘Cadillac-riding materialist’ and ‘a brown-skinned P. T. Barnum who cracked the whip in a circus of gaudy costumes, wildly gyrating acrobats and brass bands that played as if God were a cosmic hipster’. Such criticism mattered little to the devout. In Brown’s estimation, ‘Those folks were sanctified.’ The Pentecostal saints ‘had the beat … Sanctified people got more fire’.

That fire and the beat certainly inspired Ray Charles. The brilliant pianist was a great admirer of sanctified music and especially black quartets. Charles admitted to lifting material from a song called ‘You Better Leave That Liar Alone’ for his decidedly secular song ‘You Better Leave That Woman Alone’. The most obvious and potent of these retooled spiritual numbers was his 1954 smash hit ‘I’ve Got a Woman’, co-written with Renolds Richard. The pair used ‘It Must Be Jesus’ by the Southern Tones, for inspiration.

Sanctified music and gospel songs, along with the unbridled religious services that accompanied them, made a deep imprint on Jerry Lee Lewis and the early rock and rollers. But as Lewis ditched a Pentecostal ministry for a life of stardom, a major rift developed between him and his pious cousin. Lewis recorded at Sun Records in Memphis in late 1956 and shortly after became an international celebrity. A wild, piano-pounding performer, he succumbed to the lures of drugs and alcohol. Swaggart later made clear what he thought of his cousin and his wayward life. ‘Why do I need forty suits?’, he asked:

I’m clothed in a robe of righteousness! Why do I need Cadillacs and Lincolns when I can ride with the King of Kings? Jerry Lee can go to Sun Records in Memphis, I’m on my way to heaven with a God who supplies all my need according to His riches in glory by Christ Jesus.

Jerry Lee felt the sting of such rebukes. Elvis Presley, who attended the Memphis First Assembly of God church before fame made that impossible, was also hurt when Southern Baptists, Catholics and Methodists lined up to denounce his stage shows and his ‘wicked’ music. Billy Graham, America’s most famous preacher, claimed that the King of Rock and Roll’s fame was due to the ‘mystery of iniquity’, which was ‘ever working in the world for evil’.

Unsurprisingly, Jerry Lee, caught between God and the devil, was particularly vocal about his burning sense of guilt. In 1979, critic and musician Robert Palmer asked ‘The Killer’ if he believed he was going to hell for playing rock and roll. ‘Yep’, Lewis replied confidently. ‘I know the right way’, he said. ‘I was raised a good Christian. But I couldn’t make it … Too weak, I guess.’

In October 1957, the tape was rolling at Sun Records in Memphis on a recording session for ‘Great Balls of Fire’. The Assemblies of God Bible Institute, in Waxahachie, Texas had expelled the young Lewis for playing a boogie-woogie version of ‘My God Is Real’ in 1950. Seven years later he was using his talent for sinful ends and he knew it. Music should not do the work of Satan, he told Sun Records’ founder and producer Sam Phillips:

When it comes to worldly music, rock and roll, anythin’ like that, you’re in the world, and you haven’t come from out of the world, and you’re still a sinner. And you’re a sinner. You’re a sinner unless you be saved and born again, and be made as a little child, and walk before God, and be holy. And brother, I mean you got to be so pure, and no sin shall enter there. No SIN! Cause it says ‘no sin’. It don’t say just a little bit. It says, ‘no sin shall enter there’. Brother, not one little bit. You got to walk and TALK with God to go to heaven … Mr. Phillips, I don’t care … it ain’t what you believe. It’s what’s written in the BIBLE!

The Lord demanded absolute obedience and purity and Phillips could not convince Lewis otherwise. The Bible said what it said and no amount of theological flimflam about ‘interpretation’ could change that.

Other stars in the early years of rock and roll – many with connections to Pentecostal communities – were equally consumed by guilt. Johnny Cash, who attended Church of God services in Dyess, Arkansas, struggled with alcohol and amphetamines. Little Richard, too, was convinced that his stardom – and his homosexuality – would put him on the road to perdition. Somewhere along the way, he had strayed from the path of righteousness. In his youth, Richard said he liked the fiery Pentecostal services the most, where enthusiasts spoke in tongues and did the ‘holy dance’. He had long lasting memories of the singing evangelist Brother Joe May and the Pentecostal guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

While on tour with Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran in Australia in 1957, Richard decided to turn his life around. When his band mates doubted his sincerity, Richard tried to convince them by tossing $8,000 worth of diamond rings into a river. He took the Russian launch of Sputnik in 1957 to be a clear sign of the apocalypse. He planned to enroll in a Seventh-day Adventist seminary. ‘I wanted people to forget Little Richard as a Rock ‘n’ Roller’, he said. ‘I was soon to be qualified as an evangelist like Billy Graham.’ He would later say, ‘I believe this kind of music is demonic … I believe God wants people to turn from Rock ‘n’ Roll to the Rock of Ages.’

Other lesser-known rock and roll performers like Jimmie Rodgers Snow ditched the stage for the Pentecostal pulpit. The son of country legend Hank Snow, he signed a record contract with RCA, making minor, innocent hits like ‘How Do You Think I Feel?’ (1954) and ‘The Rules of Love’ (1958) and toured with Buddy Holly, Bill Haley and His Comets and Elvis. Snow told the latter that he was contemplating a Pentecostal preaching career the same year that Richard made his turnaround in Australia. Elvis could not have known that Snow would later target him and other performs as emissaries of the devil. The thin, wiry rocker-turned-pastor with hair swooped back, still sporting sideburns, blasted rock and rollers and warned teenage fans against the wild new music. He hoped to show teens, ‘the depths the devil can pull you down to. He hates you and wants to destroy you’.

In 1971, Johnny Cash underwent a second, public, conversion experience and became a regular at Snow’s Pentecostal Evangel Temple in Nashville, Tennessee. By then Cash was aligned to a new religious movement that combined countercultural views, pop music and conservative Pentecostalism. The ‘Jesus people’, as observers dubbed these new Christian hippies, played loud, guitar music, worshipped in house churches and non-denominational communities and popularised a looser style of worship. Youth pastors and ministers in the movement wore sandals and fringed leather jackets like the one popularised by Dennis Hopper in Easy Rider (1969). Billy Graham joined the Man in Black on stage and grew his hair and sideburns a little longer in keeping with the times. America’s pastor had made his peace with the style, if not the lyrical content, of rock music. Followers called the new sound Jesus music, Christian rock, or, simply, God rock.

Playlist: The Devil's Music

Like Graham, Christianity was beginning to accept rock and roll. In the late 1960s and 1970s, Christian rockers sang about the Pentecostal gifts of the spirit, the need for a spiritual revival and the fast-approaching return of Jesus. New record labels like Myrrh, Maranatha and Zondervan Records catered to a growing fan base. In the era when Americans elected their first born-again evangelical president, Jimmy Carter, Christian rock bands and Christian messages in pop music became commonplace. By the late 1970s, artists including Donna Summer, Al Green, Van Morrison, Arlo Guthrie and Bob Dylan infused their songs with Christian themes and evangelical messages. Dylan in particular was inspired by the Charismatic Movement which, much like the Pentecostals, emphasised the gifts of the spirit and promoted an open and expressive style of worship. Many charismatics, Dylan included, thought that the world would soon come to an end. Soon, there were new charismatic denominations as well as charismatic factions within mainstream Protestant and Catholic churches.

Yet prominent fundamentalists were having none of it. Some worried that the music smuggled Pentecostal beliefs into their churches. Even for some Pentecostals, the music was degenerate and had no place in their churches. ‘You cannot proclaim the message of the anointed WITH THE MUSIC OF THE DEVIL!’ shouted Swaggart in 1987. That same year Swaggart co-authored Religious Rock 'n' Roll, a Wolf in Sheep's Clothing to set out his clear views on the subject. ‘I had to bow my head in shame’, Swaggart lamented at one of his crusades. ‘My heart ached and hurt when I had to admit to … two Baptist brethren that not all, thank God, but most, most of the so-called Christian rock musicians come from Pentecostal ranks!’

Soon, Swaggart’s profile was diminished by scandal. Early in 1988, his face contorted with grief, Swaggart tearfully admitted to the 8,000 congregants of his Baton Rouge Family Worship Center that he had sinned against them and against God. His affair with New Orleans prostitute Debra Murphee had become public knowledge. The national media now focused their attention on the licentious private life of a humiliated Swaggart. Like his cousin, Jerry Lee, Swaggart now knew what it felt like to be a moral leper.

Despite holdouts against Christian rock, including the publically shamed Swaggart, sanctified pop music had become a powerful force by the 1990s. By the turn of the century, so-called contemporary Christian music – an umbrella category containing rock, rap, pop, worship and related genres – had reached an astonishing $1 billion in annual sales. It outsold jazz and classical music combined. Church services around the world now regularly featured wailing singers, heavy drums, electric guitars and synths. As Pentecostalism inspired early rock and rollers, now the influence went in the other direction. Rock music had worked its way into countless congregations. The driving beat, the interracial element, the feline sexuality and the lyrics that had made fundamentalist Christians recoil in horror in the 1950s had become mainstream.

Randall J. Stephens is the author of The Devil’s Music: How Christians Inspired, Condemned, and Embraced Rock 'n' Roll (Harvard University Press, 2018).