VE Day: The Quiet After the Peace

When VE Day finally came in May 1945 it was met with relief, exhaustion, and cynicism. Was the Second World War in Europe really over?

Across Britain, people could sense the end of the war approaching by the spring of 1945. After five-and-a-half years of death and destruction, VE Day would provide a moment of rejoicing and relief, but it would also be tinged with exhaustion and grief. Yes, there would be no more sheltering from bombers and ‘V’ weapons, or anxiously waiting for telegrams and letters from soldiers serving on distant battlefields, or bumbling about after dark in blackout cities. But the damage left by the Luftwaffe continued to scar countless streets, while more than 400,000 soldiers would never return. It would also take years to dismantle some of the most intrusive elements of state-enforced regimentation, such as the rationing of food and clothes.

As the fighting came to a bitter end, the Britons who followed the news began to learn more about some of the war’s worst horrors. In February, newspapers published pictures of Cleves – the home of Henry VIII’s fourth wife – which showed that ‘hardly a building in the town escaped damage’. If anything, Cologne – the target of the first 1,000-bomber raid three years earlier – had suffered even more. The city, reporters revealed on 12 March, ‘is over 60 per cent destroyed, with more than 2,000 acres laid flat – and there are 65 other German towns in about the same condition’.

To Bomber Command, such figures showed the efficacy of its attempt to bring the enemy’s economy to its knees. Sir Arthur Harris, who promised that the Lancasters and Halifaxes would continue to attack ‘in all weather conditions but the impossible’, even sanctioned a press statement confirming that the eradication of so much urban space signalled the completion of his ‘master-bomber plan’. Few Britons expressed any misgivings. Home Intelligence (HI) – a branch of the Ministry of Information that used both regional intelligence officers and paid investigators to gauge how people in all parts of the country thought about the war – even reported ‘tremendous satisfaction’ when Bomber Command began launching 5,000-bomber raids, with many people convinced that this level of ‘area bombing’ must ‘shake the confidence of the most optimistic Nazi’.

Then came news that Allied troops had liberated Nazi concentration camps. Over 18,000 people had died of disease and starvation in the Belsen camp during March alone, and many of the survivors were suffering from hunger or typhus when Richard Dimbleby of the BBC arrived alongside a platoon of British soldiers on 15 April. On his return to the press camp a few hours later, one colleague thought he was ‘a changed man’. Shaken by what he had seen, he broke down in tears as he began to speak into the microphone. On learning that the BBC News Room was refusing to broadcast his recording until receiving verification from newspaper reports, he made an angry phone call to London. When his editors relented, the home front learned how Dimbleby had found himself:

in the world of a nightmare. Dead bodies, some of them in decay, lay strewn about the road and along the rutted track … The dead and dying lay close together. I picked my way over corpse after corpse in the gloom.

At first, many newspaper editors were equally hesitant about running this story. Until now, the Daily Mirror and Daily Worker had been alone in publishing graphic details about liberated death camps in Eastern Europe. The rest had worried about both the veracity of information emanating from the Soviet Union and the prospect of repulsing their readers. That Belsen had been liberated by the British overcame the first obstacle. The truly shocking nature of the photographic record helped to remove the second. ‘So horrible were many of the pictures’, observed the Newspaper World after interviewing Fleet Street editors, ‘that most newspapers indicated that they had made a selection of the less gruesome prints.’ These were bad enough, but to the editors’ surprise few readers protested. ‘We had only one letter of objection’, revealed the Daily Mail, ‘whereas we have literally hundreds approving the publication of the stories.’ ‘Tremendous reaction from readers’, agreed the News Chronicle, ‘with hardly a letter in criticism of publication. On the contrary, they think we have done a real service by publishing them to show people the real face of fascism.’ When the Daily Express held exhibitions of the images in both Trafalgar Square and its Fleet Street office in May, with showcards proclaiming ‘SEEING IS BELIEVING’, Mass-Observation – an organisation that used more than 1,000 volunteers to detect the mood in various communities – reported that people filed past ‘in horrified silence’. ‘Everyone who was interviewed’, the surveyor remarked, ‘felt the deepest horror and revulsion … Several people had found themselves unable to look at all of them.’

Despite the wave of revulsion sweeping the country, Mass-Observation found surprisingly little elation at the prospect of victory. ‘I mean everything will go on as before’, remarked one interviewee in early April, ‘and there will be less food than ever, and I don’t suppose my husband will come home for months and years, and they will nag us about winning the peace or something, just as they nagged us about the war.’ ‘I kind of feel I can’t believe in it any more’, added another, ‘after all these years I can’t believe it can ever really finish. I think the other girls feel the same; they all say: Wouldn’t it be lovely, but it can’t be true.’ Even the major news events coming out of Germany initially failed to shake this jaded, cynical mood. When Hitler’s death was announced on 2 May, one survey found ‘great excitement, although equal scepticism’, with ‘one in four people’ stating that ‘they did not believe it’. ‘What again?’ was a typical response. ‘I’m fed up with hearing that bloke’s dead!’

A scarcity of flags

‘The week immediately preceding the declaration of peace’, noted Mass-Observation, ‘was a week of confusing and fluctuating emotions ... People were tired of successive announcements, constantly contradicted.’ About the only story that did spark a sense of eager expectation was the plan for what promised to be the biggest party since 1918. In the middle of April the Ministry of Labour unveiled details for a paid public holiday on the day after the announcement of a ‘ceasefire’ in Europe. Workers in essential industries would remain in their posts, which raised the question of who was now to be considered vital. Did this include railway workers, with the enormous demand to travel to London for the festivities? Or journalists, given that the public would be desperate to read and hear about the big day? After some haggling, both sectors agreed to intricate compromises, including double pay for those who worked the holiday as well as time off at a later date. Other long-suffering labourers, such as miners, also negotiated their own – often generous – deals.

Many intended to use the holiday to get roaring drunk. To facilitate this simple ambition, the government guaranteed that licences for drinking-hours extensions would ‘be considered sympathetically’, while breweries promised pubs ‘an additional third of one week’s supplies’ for ‘V-drinks’. The first week of May also saw a run on the new must-have fashions, from Union Jack scarves and ribbons to hair-slides and rosettes. Flags became particularly scarce, ‘and any attempt to buy one was’, as Mass-Observation reported, ‘a hectic undertaking, involving much queuing’.

Yet this enthusiastic preparation still came with a good deal of grumbling. What about the children?, asked one Walthamstow woman in the letters page of the Daily Mirror: ‘They should have some pleasure on V-Day. Why not a free cinema show or free sweets?’ And what about those London hoteliers who were massively hiking their prices. ‘Is the Government going to sit back apathetically and allow these profiteers such liberty?’ asked two women from Dartford.

As the country basked in a mini heatwave, some visitors to the capital saved money by sleeping on the streets. During the day, they gravitated towards landmarks such as Parliament and St Paul’s, where they could see batteries of arc-lamps being erected. When a reporter asked one workman how many lamps there were in total, he joked: ‘I can’t tell you; it’s a government secret.’ There was nothing furtive about the plans of the most senior figures, however. Both Churchill and the king announced they would make major speeches to the nation the day after Germany’s unconditional surrender had been confirmed. The only problem was getting reliable information about this last act of the European war. Although a German delegation signed the formal surrender document shortly after 2.30 on the morning of Monday 7 May, the Soviets insisted that this news be held until 3pm the following day. When first the Germans and then a US reporter divulged the details a day early, Mass-Observation recorded that ‘a rather unexcited expectancy was the dominant mood, coupled with the usual uncertainty and confusion’.

Across Britain, most people went to work as usual that Monday morning, albeit in hope that they might suddenly be granted a holiday. ‘News listening and newspaper reading’, noted Mass-Observation, ‘rose to a peak’. In central London a light rain began to fall in the late afternoon, briefly dispersing the crowds that had gathered along Whitehall. In the West End the mood remained muted into the early evening, as the growing multitudes continued to await official confirmation. Then at 6pm the BBC announced that the following day would become VE Day. Soon, hooters and sirens began blaring out a ‘victory tune’ in the London docks. In Stepney, children rummaged through Blitz ruins for rafters and mattresses – anything that would burn – as bonfires erupted ‘on bombed sites, at kerb sides, and in cul-de-sacs’. Within an hour the impromptu party spread across the city. ‘A pile of straw’, observed one reporter:

filled with thunder-flashes salvaged from some military dump spurted and exploded near Leicester Square. Every car that challenged the milling, moiling throng was submerged in humanity. They climbed on the running boards, on the bonnet, on the roof. They hammered on the panels. They shouted and sang.

An alliance victory

After this spasm of rejoicing, the revelry on 8 May was more restrained. Even around Piccadilly and Whitehall, Mass-Observation noted, ‘most people’s participation was confined to singing and cheering when called upon, and admiring the abandonment of others’. ‘Outside central London’, recorded the commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, ‘street parties, bonfires, and fireworks were the most popular forms of celebration. No trouble or incidents occurred anywhere’, he added, not even when many pubs ran out of beer, for the happy crowds ‘showed no resentment at this’.

As well as being good-natured, the 8 May festivities also contained a little more structure than those of the day before, as first the prime minister and then the monarch addressed the nation. Both men reiterated familiar themes, Churchill emphasising how Britain had ‘stood alone’ in 1940, while the king paid tribute to both the valiant men fighting overseas and the uncomplaining civilians who had suffered at home. Yet these two speeches also left listeners in little doubt that this had been an alliance victory, made possible ‘by the military might of Soviet Russia’ and ‘the overwhelming power and resources’ of the US. Political unity at home had been crucial, too, a fact underlined when Winston Churchill and Ernest Bevin appeared together on the Ministry of Health balcony and called for ‘three cheers for victory’.

Then there was the sight of the two princesses mingling with the masses, Elizabeth proudly wearing the ATS uniform that she and another 200,000 women had worn during the war. The Daily Mail described this as ‘an English crowd, patient, tolerant, good-humoured, gay’. But it also stressed that Britain had become ‘a polyglot people. For the populace of London’, its front-page story noted, ‘is the microcosm of the peoples of the Free World. A Dutch flag escorted by Netherlanders forces its way through the throng. Later a Belgian flag was borne by those who bore its allegiance. Scattered through the multitude were the representatives of America.’

The next day, as the public enjoyed a second bank holiday, the Ministry of Information announced the lifting of restrictions on publishing weather forecasts (which since 1939 had been deemed a state secret lest they provide the enemy with an advantage in planning air raids) – ‘a victory gift’, it explained, ‘that will help Britons to plan their VE-Day Plus One celebrations’. Soon, censorship on other matters ‘decreased considerably’. A revised edition of proscribed subjects published on 10 May contained just 50 D-notices – the government’s instructions to the press on what information to avoid as ‘prejudicial to national interests’ – compared to the 95 that had been in effect a week earlier, with most of the remaining restrictions relating to technical issues. A more ruthless purge was not yet possible, however, for, as Churchill reminded the nation in his VE Day broadcast, ‘Japan, with all her treachery and greed, remains unsubdued’.

The atomic age

That the Pacific War continued to rage was one reason why many members of the weary nation remained tetchy and anxious the moment the bunting came down. Exactly a week after VE Day, the government announced that all British troops ‘specially trained for Pacific warfare’ would be sent to the Far East.

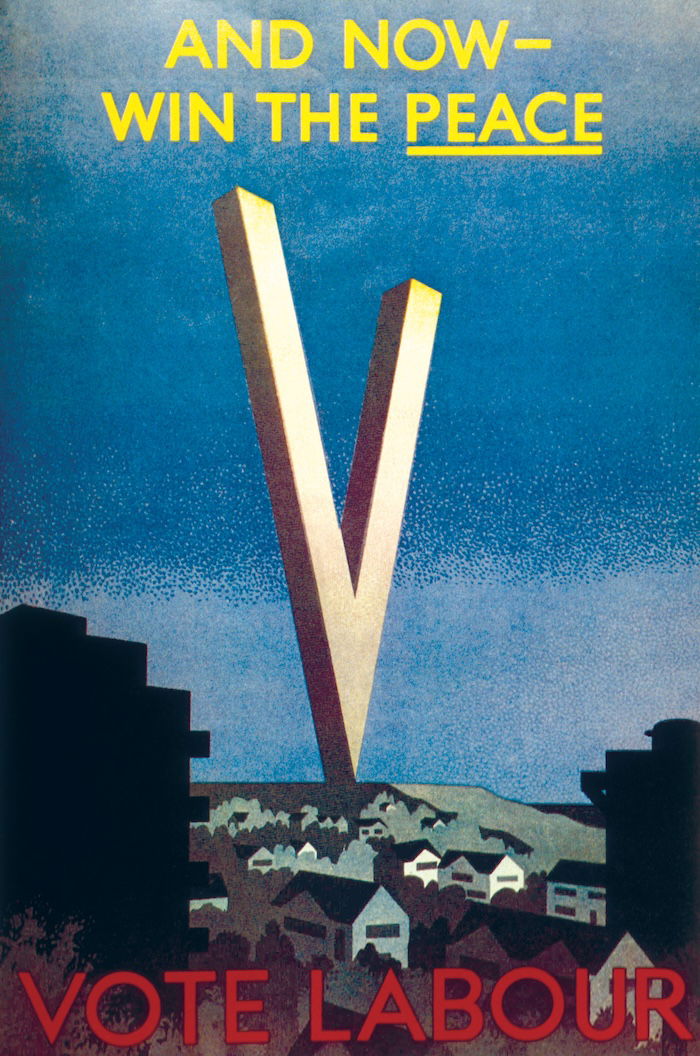

Shortly after, Mass-Observation found that some people were already missing the wartime camaraderie, while many simply felt a ‘sheer blind weariness and fed-upness at continued shortages, discomforts, uncertainties’. When Churchill dissolved Parliament and called a general election, the mood only worsened, especially once the politicians who had worked together for the past five years began directing ‘abusive denunciations’ at each other. ‘It is difficult to conceive of an electioneering technique’, concluded Mass-Observation, ‘better calculated to lower the morale of an already dispirited electorate.’

Labour’s stunning landslide victory on 26 July generated little rejoicing. Opinion polls found that 58 per cent thought the general election had been a ‘bad thing’. As well as rekindling a vicious partisanship, many felt it should have been postponed until the Far Eastern fighting was over.

When VJ Day finally came on 15 August, London held another party, with large crowds gathering around Buckingham Palace and midnight revellers dancing in Piccadilly. Even more than in May, however, the underlying mood remained bleak. One major fear was the collapse of the great wartime alliance, which might mean another world war. Many people quizzed by Mass-Observation fretted that Joseph Stalin had no intention of abiding by the agreements he had recently struck at the Potsdam Conference with the new prime minister, Clement Attlee, and the new American president, Harry Truman, especially those relating to Germany and Poland.

Many more were troubled by the way that Truman had ended the Pacific War. First, he had dropped two atomic bombs on Japan. Then, on 19 August, he suddenly announced the end of Lend-Lease – the measure by which US economic aid had flooded across the Atlantic since 1941 – which immediately threatened to bankrupt Britain. While parliamentary correspondents described this second move as ‘a body-blow’ to the new government, Attlee openly revealed his dismay. ‘We can, of course, only demobilise and reconvert gradually’, he told the Commons the following week, ‘and the sudden cessation of a support on which our war organisation has so largely depended, puts us in a very serious financial position.’

Against this gloomy backdrop, it was scarcely surprising that Mass-Observation found that a mere 32 per cent of Britons were cheerful by the end of August, compared to 57 per cent who felt depressed. The new atomic era was generating some of this despondency, since a large majority considered the terrifying weapon a thoroughly ‘bad thing’. ‘Marvellous!’ exclaimed one sarcastic respondent. ‘Just give us another five years and it’s going to put paid to all our little problems. No more rationing, no more income-tax, no more anything.’

As this comment implied, a major complaint was that peace had brought no real material change. Most people recognised that the new government needed time to confront the chronic housing shortages, improve food supplies, and implement its promise to provide social security from the cradle to the grave. There was even some awareness of the immense challenges Britain faced overseas. The Empire had been fundamentally weakened by the defeats in Singapore and Burma in early 1942, followed by Gandhi’s Quit India movement and the Bengal famine that had killed 10,000 people a week by the end of 1943. When the guns fell silent, Britain also became the occupier in northern Germany, making it responsible for much of the area destroyed by Bomber Command. Partly for this reason, many men in uniform would not be coming home quickly. ‘Although the actual fighting is over’, Attlee informed Parliament on 16 August, ‘we have not come to the time of full demobilisation. We have to keep the strength of our Armed Forces at a high level to meet our military commitments.’ Few in his own party were convinced by this argument. In early September, backbench Labour MPs, highlighting the ‘widespread dissatisfaction’ in their constituencies, even began lobbying ‘the Government to take the country into its confidence and explain exactly why demobilisation under the present scheme could not be faster’.

Not until the first half of 1946 did the demobilisation process accelerate, disgorging almost two million men from military service. The country they returned to remained scarred by bomb damage, plagued by shortages, and desperate for Labour to implement its manifesto promises. In some areas, Attlee’s government responded effectively, creating the National Health Service and building thousands of new homes. But a census at the end of the Parliament in 1951 revealed that the shortage of dwellings remained at around the million mark. By that time, too, Labour had been unable to end rationing, providing the Conservatives with the powerful slogan that, while Labour was the ‘killjoy party’, they would ‘set the people free’.

Exhausted nation

During the war, the government had often worried about excessive mood swings – of a public too eager to depict every military advance as the harbinger of impending victory, raising the possibility of a dangerous downturn in the event of a military setback. When final victory came, the problem was not one of an excessive party followed by a massive hangover. On VE Day, observed Mass-Observation:

usually crowds were too few and too thin to inspire much feeling and on VE night most people were either at home, at small private parties, at indoor dances or in public houses, or collected in small groups around bonfires, where there was sometimes singing and dancing, but by no means riotously.

Britain by the end of the war was simply too exhausted to party too hard. After six years of intense sacrifice, people were relieved that the fighting and dying had finally ended. But they were also impatient for a real change that would lift them out of wartime austerity.

Steven Casey is Professor of History at LSE.The Skeptic Isle: How the British Government Sold the Second World War will be published by Oxford University Press in August.