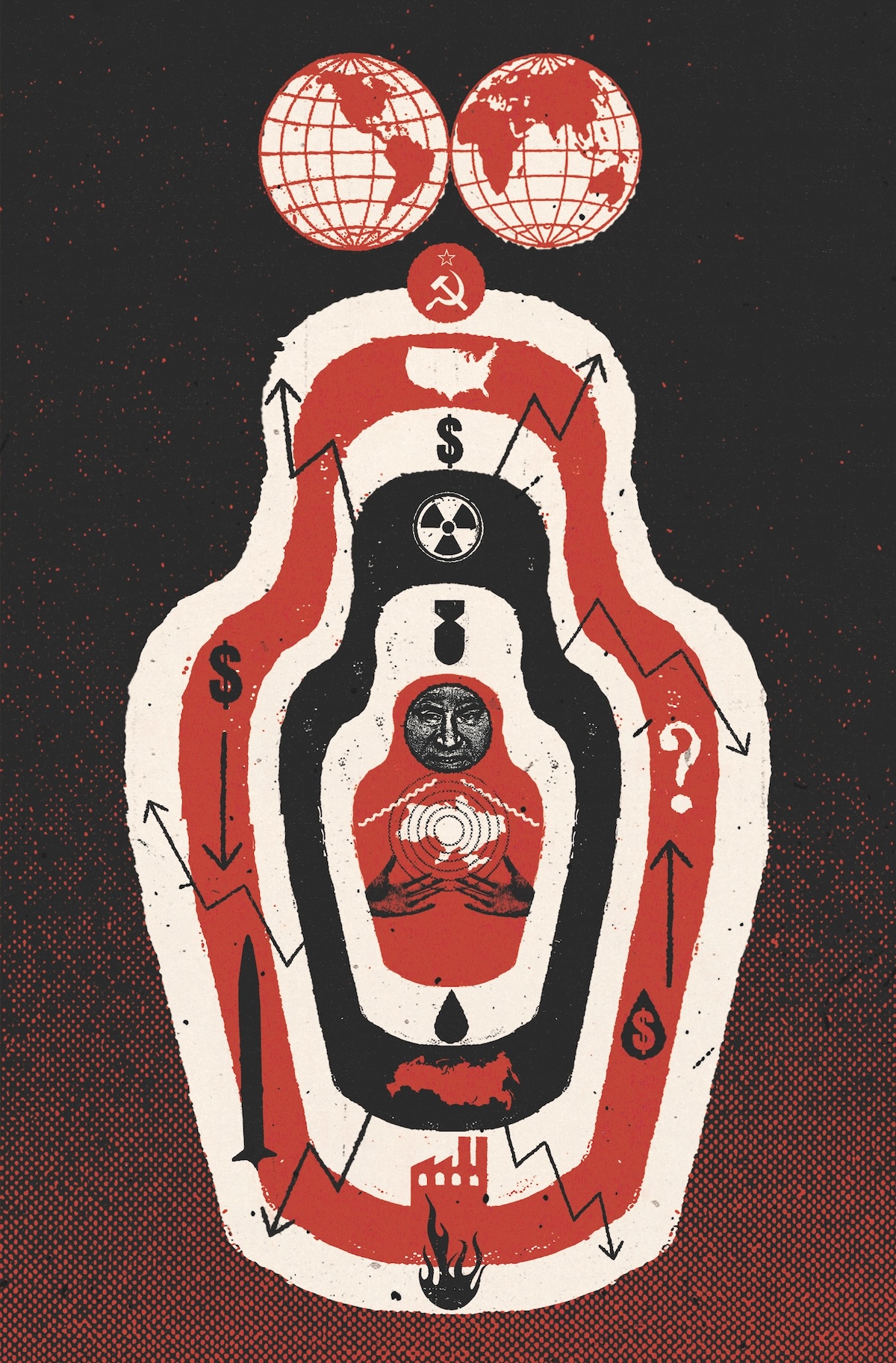

Doing Business with Russia

Russia’s entry into the global economy was met with glee by international firms in the early 1990s. The exodus has been just as sudden.

When the Soviet Union fell apart in 1991, its centrally planned economy went down with it. But the end was also a beginning: from a business point of view the birth of the Russian Federation meant that suddenly, and unexpectedly, opportunity was everywhere. ‘No one in the world was prepared for the fall of the Soviet Union’, said Bernie Sucher, an American businessman who would become one of the leading figures in Russian investment banking. ‘Nobody had that in their business plan.’