Searching for the Soul of the Beaver

Are beavers beasts or fish? For medieval philosophers, this was an important question with implications for the dining table.

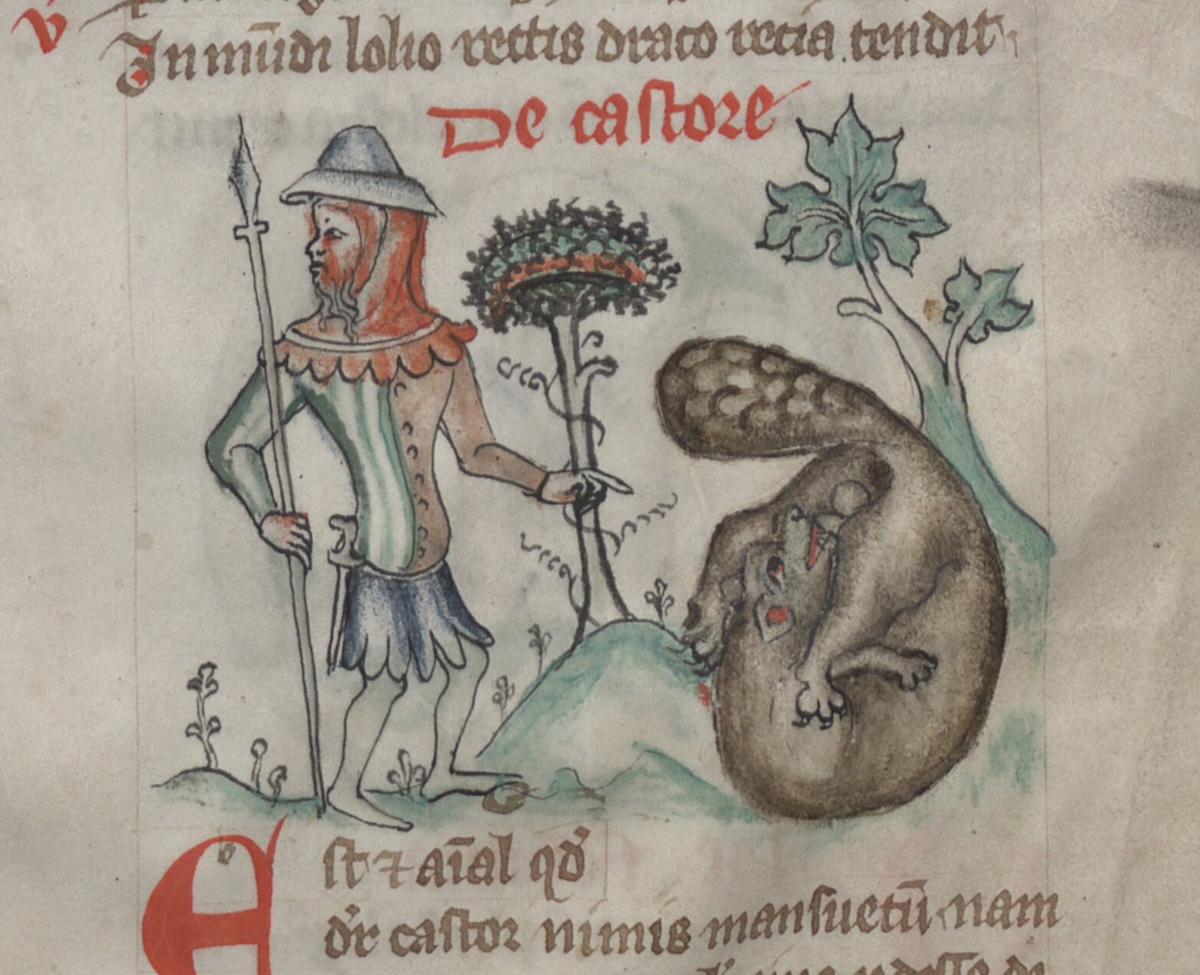

In medieval Europe beavers were hunted extensively, which led, by the 12th and 13th centuries, to their extinction in England and Wales, and in Denmark by the tenth century. The animals were killed not only for their fur, but also for their scent glands. Despite being present in both genders, the glands were mistaken for the male beaver’s genitalia. They contained castoreum, which was used as an almost universal medicine for most conditions. Bestiaries – medieval books containing descriptions of real-life and imaginary animals, accompanied by moralising tales – stated that a beaver could offer his genitalia to hunters in exchange for his life. If the same beaver encountered hunters again, he would lie on his back, demonstrating that his testicles had already been taken.