The Englishman Who Cried ‘Let Ireland Go’

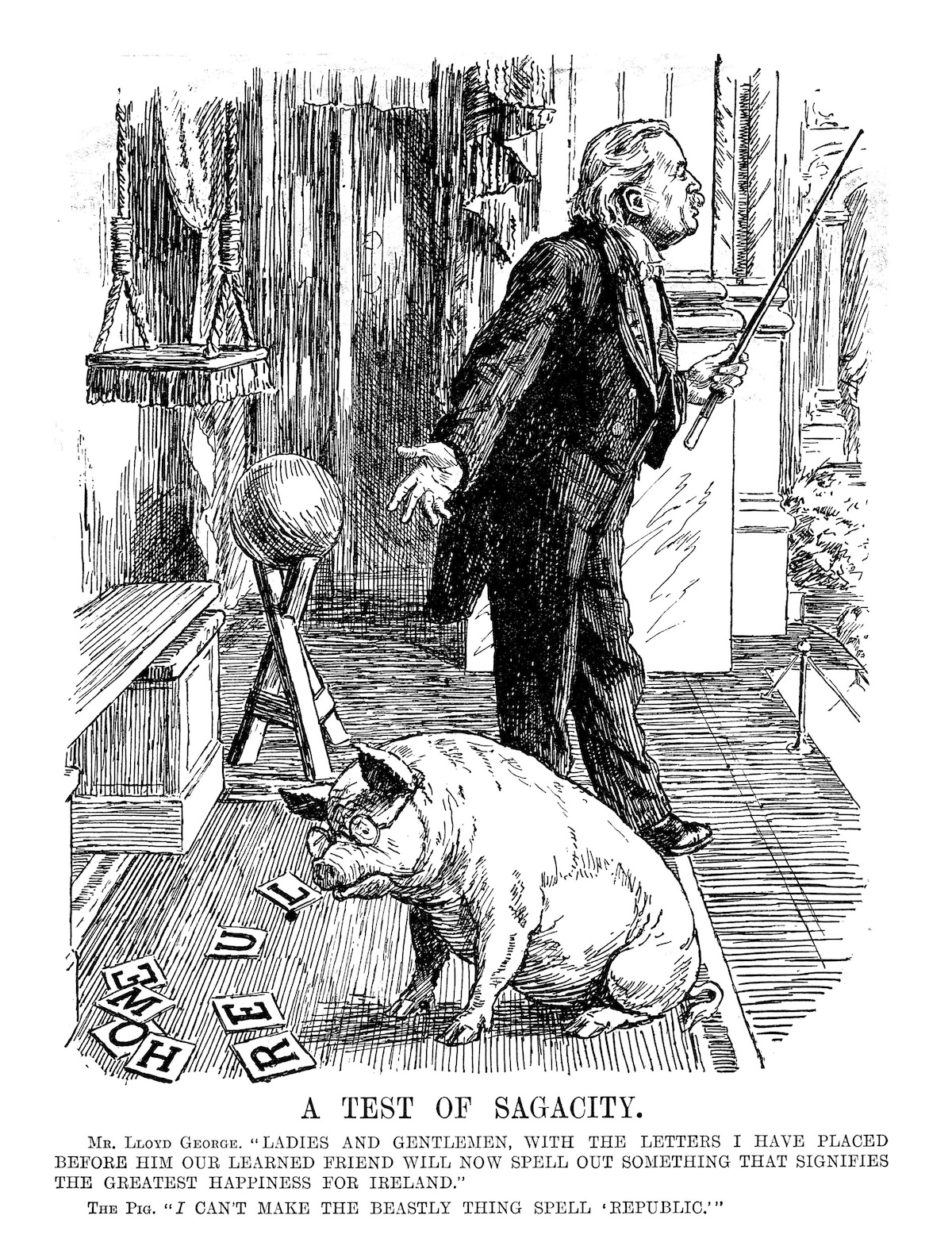

In 1920 the English writer Jerome K. Jerome set out the arguments in favour of Irish home rule.

‘Let Ireland go, with God’s blessing and a shake of the hand’, wrote Jerome K. Jerome in May 1920. This was a crucial year in Anglo-Irish relations, when Irish men and women were taking up arms against British rule in Ireland.

The English author Jerome Klapka Jerome (1859-1927) was not known for writing on politics but for his plays, books, and magazine articles. He is best remembered today for Three Men in a Boat (1889), a humorous tale in which three friends take a boating holiday on the River Thames. This, combined with how rare it was for such opinions to be published in the English press, particularly by such a famous author, makes his article on British policy towards Ireland all the more interesting.