‘Lower than the Angels’ by Diarmaid MacCulloch review

Lower than the Angels: A History of Sex and Christianity by Diarmaid MacCulloch reminds us that when it comes to sexuality and gender, scripture is often contradictory.

A majority of Christians today believe that their faith involves seeing heterosexual, monogamous, and procreative sexual intercourse as the norm. African Anglicans and Russian Orthodox denounce homosexuality as a harbinger of Western degeneration; the pope joins American evangelicals in detesting abortion. The Holy Family stands with the nuclear family. Diarmaid MacCulloch’s irritation at such ahistorical conservatism has moved him to track the sheer variety of Christian theologies of sex over the ages with Gibbonian wit and occasional asperity. Lower than the Angels is an intricate survey with a clear moral: Christians should think twice before casting the first stone.

The Bible was always too contradictory and opaque to rule Christian thinking on gender or sexuality. The currency and meaning of proof texts fluctuated with the ambitions of Church leaders and the elites to which they catered. Outside influences mattered too. Christians absorbed monogamy from the Classical societies in which they were at first an invisible minority, even if they abhorred their resort to abortion and infanticide. They studiously overlooked the polygamists of the Hebrew scriptures, just as they rejected male genital mutilation. Their puritanism was also more Classical than Jewish. Plenty of wild men – and some wild women – in Egypt and Syria tried to relinquish sexuality altogether, with Origen even castrating himself. Yet influential theologians emulated Roman thinkers in calling men to show self-restraint, but not abstinence, in their sexual lives.

The New Testament encouraged this chastened attachment to marriage. Paul recommended that it was better to marry than to burn with lust. He also said that husbands and wives owed each other sexual satisfaction – the ‘marital debt’. The main thing was not to get carried away: Jerome condemned men who loved their wives too much as adulterers. Only in the East were attitudes less neurotic. Because Greek theologians regarded all sexuality as fallen, they were less flustered about what sort or degree of intercourse was sinful. Societies such as Russia that adopted Orthodoxy inherited this ‘sane because sex-negative’ approach.

Missionaries beyond Rome had a hard job in getting pagan societies to accept the austere mores of the Mediterranean. Its elites were loath to give up the concubines whose children ensured their biological succession. Elsewhere too, Christians bent to the requirements of the powerful. Bishops from the Dyophysite Church of the East could not follow their Western counterparts in adopting celibacy, because it was a capital crime in Zoroastrian Iran.

It therefore took centuries to build Christendom – the word is an Anglo-Saxon coinage for a sacred society permeated with Christian morals. From the 11th century, a crusader papacy with a newly exalted vision of the Eucharist demanded celibacy from the priests who celebrated that mysterious sacrifice. The onus was now on the laity to copulate. The clergy now presided over marriages, which joined the Eucharist as one of seven sacraments. Spirituality now embodied family values: Joseph became a venerable figure, rather than a complication for the perpetual virginity of Mary; Christians decorated cribs and visited ‘Holy Houses’ at Walshingham and Loreto, childhood homes of Jesus that had miraculously landed there from Palestine.

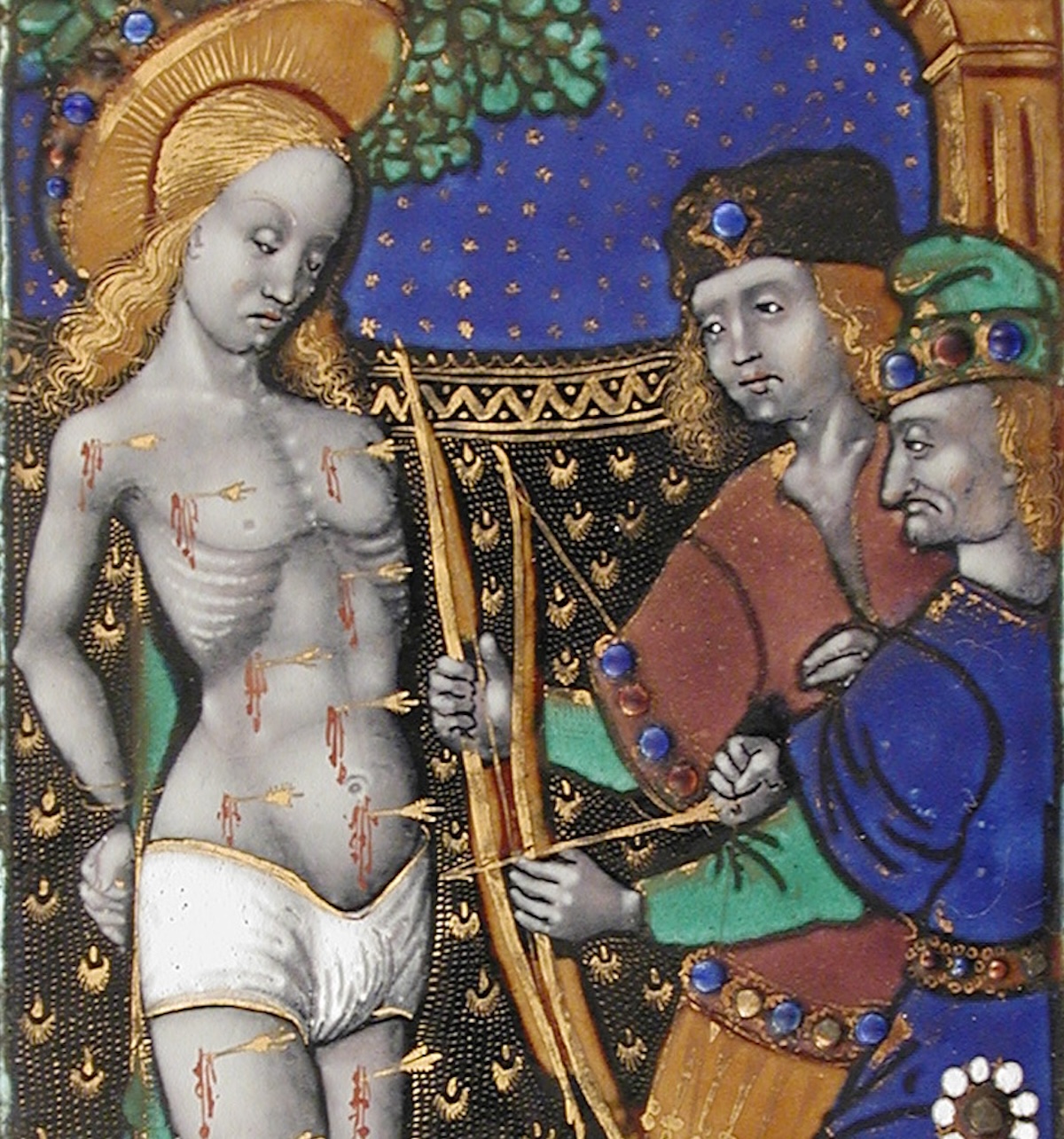

Charges of sexual as well as intellectual deviance motivated the persecution of heretics: the Bogomils of Bulgaria were the first ‘buggers’. Christians, who massacred Jews after accusing them of desecrating Eucharistic wafers and murdering saintly children, now represented the circumcision of Christ as their first act of sacrilegious violence. Their hatred had its blind spots. There was no concerted harrying of homosexuals. Monks were free in their homosocial cloisters to develop a rich literature of mutual infatuation. Spirituality and mysticism were gender fluid, with beardless angels symbolising life beyond sexual binaries.

The Reformation challenged but finally restated the code of Christendom in a different key. Protestant ministers who rejected celibacy presented their new families as models of monogamy. Martin Luther’s scriptural defence of polygamy found few takers and was quickly forgotten. Tolerance for prostitution and children born out of wedlock declined.

Although both Protestantism and Catholicism relaxed their grip on Western societies in the 18th and 19th centuries, it is unclear how quickly sexual behaviour shifted as a result. MacCulloch suggests that commerce, print, and urbanisation freed minds and bodies from clerical control. He takes an ‘appreciable number’ of trans marriages as one high water mark of this emancipation – although the monograph he cites found only ‘dozens’ of such cases. And while Christendom wobbled at home, missionaries exported its clenched mores to the extra-European world.

It was technological change that really scuppered the churches. The rubber condom and the contraceptive pill separated intercourse from procreation, making sex fun and undermining the argument that homosexuality was against nature. Some Christians responded more nimbly than others. MacCulloch credits his fellow Anglicans with readily taking to condoms and the defence of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. By contrast, Rome’s unhappy celibates made its institutions hotbeds of sexual abuse and ‘poisonous silence’. Pope Paul VI’s fossilised vision of natural law prompted his last-ditch stand against contraception in 1968.

The sixties may not have swung for Catholics, but MacCulloch’s conclusions breathe the optimism of that decade. Ever more people will follow their authentic desires in future, with the blessing of Jesus, a ‘playful’ teacher innocent of the repression founded on his name. This oddly frictionless view of future sex expresses a liberal Anglican hope that such lingering prejudices as homophobia are peculiarly Christian forms of bigotry, which will fade when the churches complete their enlightenment. It is the last and certainly the nicest of the faith commitments charted in this compelling book.

-

Lower than the Angels: A History of Sex and Christianity

Diarmaid MacCulloch

Allen Lane, 688pp, £35

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Michael Ledger-Lomas is a historian of religion.