‘All His Spies’ and ‘Spycraft’ review

All His Spies: The Secret World of Robert Cecil and Spycraft: Tricks and Tools of the Dangerous Trade from Elizabeth I to the Restoration bring Tudor and Stuart espionage in from the cold.

Tudor and Stuart spies appear to be coming in from the cold this summer. The Cecils – subject of a now-complete trilogy by Stephen Alford – were the most powerful royal ministers for over five decades, a reign begun by William, 1st Baron Burghley and inherited by his son, Robert, who took over the role of spymaster from his father and became secretary of state to both Elizabeth I and James I. Robert’s intimacy with his sovereigns is reflected in Elizabeth’s pet name of ‘pygmy’ for him, a reference to his short stature caused by severe scoliosis. To James, Robert was his ‘Little Beagle’, the smallest of English hunting dogs, but also a word meaning spy. Robert was indeed more than that to the Scottish king: it was he who eased James’ accession in England in 1603. Two years earlier James had urged his ambassadors at the English court to give Robert the full assurance of his favour as the man who, in James’ opinion, was ‘king there in effect’.

Despite his prominence at not one but two royal courts, Robert Cecil’s life has been obscured, both by the dominance of his father and by his own instinctive caution and secrecy when committing pen to paper. His father’s close attention to Robert’s education was aimed at preparing him for royal service; his easy passage into Elizabeth’s confidence was resented by many of his contemporaries. From his late 20s, Robert increasingly took on the work of the secretary of state in tandem with his father, who died in 1598. Robert became the leading English minister until his own death in 1612, aged 48.

These were years when fears and rumours of treason, imminent Spanish invasion and Catholic assassination plots against Elizabeth were rife. Robert was at the centre of the intelligence gathering and policy-making intended to protect the queen. He took decisive action in bringing traitors to justice and was instrumental in securing evidence against Elizabeth’s personal physician-in-chief, Dr Ruy Lopez, accused of conspiring to poison her in 1594. Robert also participated in the trials of both Robert Devereux, 2nd earl of Essex after his failed coup against Elizabeth in 1601, and of the Jesuit priest Henry Garnet for complicity in the Gunpowder Plot. Much of the evidence against these men was obtained from Robert’s network of spies, an unreliable group of chancers, double, even triple, agents and Catholics, who were given a certain amount of immunity for ratting on their contacts abroad. Spies could not always rely on their patrons for help and their masters often did not much care for them. When George Nicolson, Robert’s agent at the Scottish court, sent him a ‘fair standing bowl’ as a New Year’s gift, Cecil promptly sold it.

As Elizabeth reached the end of her life, rumours about who would be her successor reached a crescendo. Cecil felt the need to secure his own position by assuring James of his loyalty. In private letters to the Scottish king, he diplomatically signalled to James that he favoured his succession and no other; upon his accession, Robert Cecil was rewarded with a series of titles. But his success as a minister and confidant to monarchs was marred in 1610 by the unravelling of James’ plan to secure a regular, fixed income with the agreement of the English parliament. James blamed the failure of the ‘Great Contract’ on his chief minister ‘being a little blinded with the self-love of your own counsel’. It was a mild enough rebuke and came with the king’s assurances of his favour, but, his health declining, Cecil felt the blow keenly.

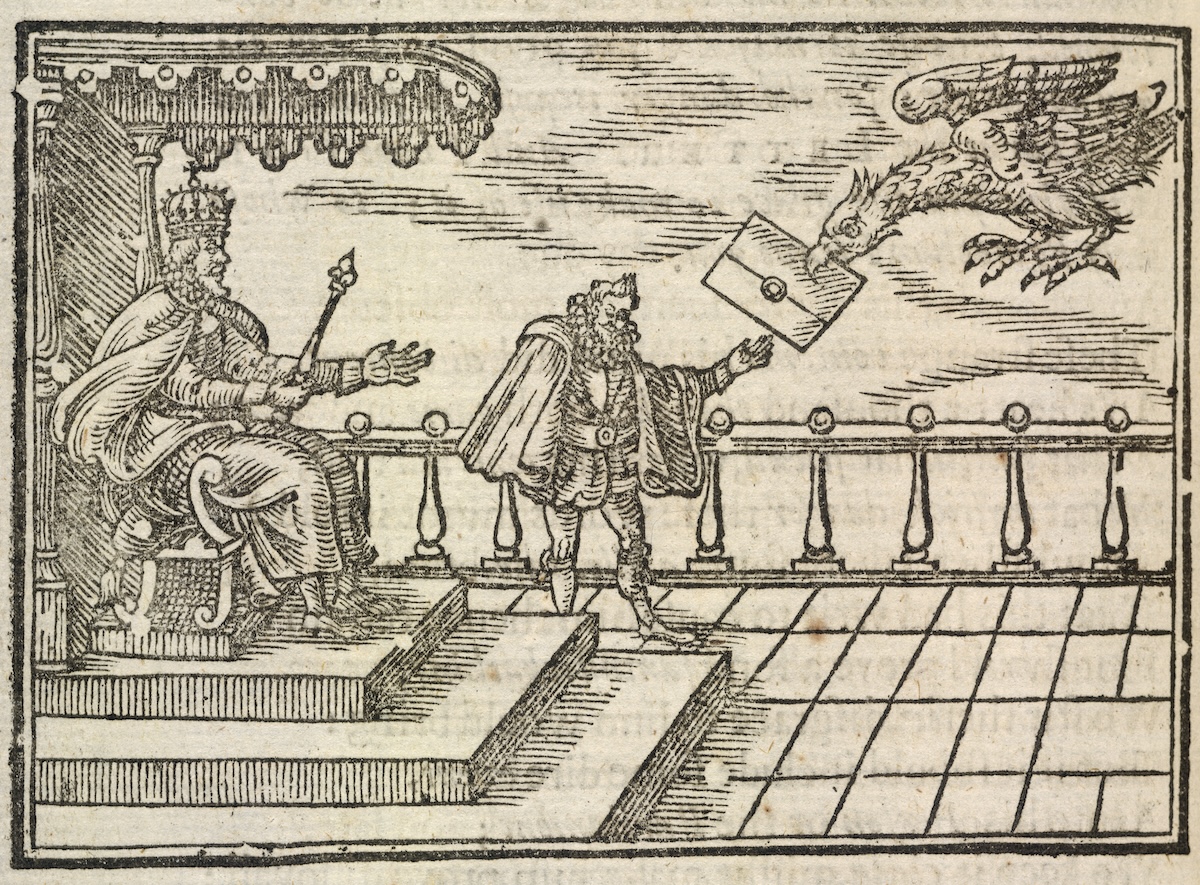

Stephen Alford is well familiar with Robert Cecil and the intrigues of the wider royal court. One of the great assets of All His Spies is his skilled use of the original manuscripts written by the Cecils and their contemporaries, from Robert’s ‘quick and fluid’ pen movements on one document, to the improving handwriting of his teenage son, William, in his letters to his father. This forte is shared by Nadine Akkerman and Pete Langman in Spycraft, a book concerned with the material world of espionage. Here we learn about the measures taken by rulers, politicians and diplomats to keep their most private correspondence secure and the Herculean efforts of their enemies to uncover their secrets. These include the use of invisible inks such as lemon juice or diluted alum, elaborate letter-locking techniques, the use of increasingly complicated ciphers and codes, and even the precise duplication of letters that had been damaged by attempts to break a seal or reveal hidden messages with heat from a candle or fire. Elizabeth I’s privy councillors employed individual virtuosi who were adept at these dark arts. Later, John Thurloe, secretary of state under Oliver Cromwell, would establish an entire government department of intelligencers, who could learn from each other.

Arthur Gregory was one such early virtuoso, so adept that he could open and close a letter without detection. His workshops at his home in Whitechapel and in the Tower of London were laboratories where he experimented with methods for counterfeiting the seals on letters and the use of noxious ingredients for making invisible inks. There were, naturally, hazards of the job: Gregory’s close proximity to substances such as quicksilver or liquid mercury had unfortunate effects on his nervous system, including a dramatic swelling of an eye in 1586 and, a decade later, the development of an unsteady tremor of the hand. Couriers could also be exposed to toxic materials when miniaturised messages were prepared in lead casings, sometimes fashioned like bullets, that were small enough to be swallowed.

The uncertain life of the spy is demonstrated by Thomas Phelippes, a gifted linguist and cryptographer best known for deciphering the Babington Letters in 1586, sealing the downfall of Mary, Queen of Scots, and who later worked for the Cecils. Phelippes’ role in bringing Mary to the executioner’s block did not endear him to her son, James I, and his double dealing over the Gunpowder Plot eventually landed him in the Tower of London. He remained there in debt and despair for nearly 20 years.

Spycraft is the sequel to Akkerman’s Invisible Agents: Women and Espionage in Seventeenth-Century Britain, and both she and Langman set out to emphasise that women were actively engaged in the realm of intelligence, comparing, for example, the art of letter locking – carefully folding and closing a letter through slits made in the paper – with needlework. The complex spiral lock was certainly used by Mary, Queen of Scots, a renowned needlewoman, who may have learned the technique from her mother-in-law, Catherine de’ Medici. More routinely, Mary employed secretaries, even while imprisoned, to encipher and decipher her clandestine letters; it was, however, on the basis of their testimony that she was later convicted of treason. Perhaps mindful of these dangers Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia, did the ciphering herself rather than run the risk of involving others.

Women were also employed as couriers by both the English royalists and parliamentarians and during the Thirty Years War in Germany, in part because they were less likely to be suspected of carrying top secret messages. Suspicion was rife during the period; there are examples of suspected couriers, both men and women, being forced to take a laxative or an emetic in order to void any papers they had swallowed. In 1643 Katherine Howard, Lady d’Aubigny was given a commission of array by Charles I to raise royalist forces in London. She hid the document in her hair, presumably styled in an impressive updo.

Spycraft is not only a textual tour de force, but contains a wealth of explanatory images of the authors’ recreations of locked letters and forged signature stamps. Both books demonstrate that despite the clandestine nature of spies and counterspies, they have left much evidence of their activities – for those able and willing to undertake the painstaking archival research necessary to bring their secrets to light.

-

All His Spies: The Secret World of Robert Cecil

Stephen Alford

Allen Lane, 400pp, £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link) -

Spycraft: Tricks and Tools of the Dangerous Trade from Elizabeth I to the Restoration

Nadine Akkerman and Pete Langman

Yale University Press, 348pp, £20

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Jackie Eales is President of the British Association for Local History and a Professor of Early Modern History at Canterbury Christ Church University.