The Publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four

On 8 June 1949, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four was published. His final novel, its themes had been present throughout his literary career.

His first published work, a poem, appeared in the autumn of 1914. ‘Awake! Young Men of England’ was a call to arms for a nation newly at war. He was 11 years old and his name was Eric Blair.

He took up the pen-name George Orwell in 1932 for his first book. (Other names considered included P.S. Burton and H. Lewis Allways.) But his prep-school days stayed with him. Orwell, said Cyril Connolly, a schoolmate and lifelong friend, was ‘a rebel in love with 1910’. Others saw deeper roots still: to Julian Symons he was ‘an Edwardian, even a Victorian figure’; to Stephen Spender he was ‘traditional in a way which goes back … before industrialism, to the English village’.

Looking back on school in ‘Such, Such Were the Joys’, a vituperative essay written in the 1940s, Orwell remembered it as a system in which ‘to survive, or at least to preserve any kind of independence, was essentially criminal’. A sense of beleaguered individualism colours much of his fiction. John Flory, the central character in Burmese Days, is oppressed by imperialism; it makes him ‘live inwardly, secretly, in books and secret thoughts that could not be uttered’. Gordon Comstock in Keep the Aspidistra Flying is oppressed by capitalism: he ‘declared war on money; but secretly, of course’.

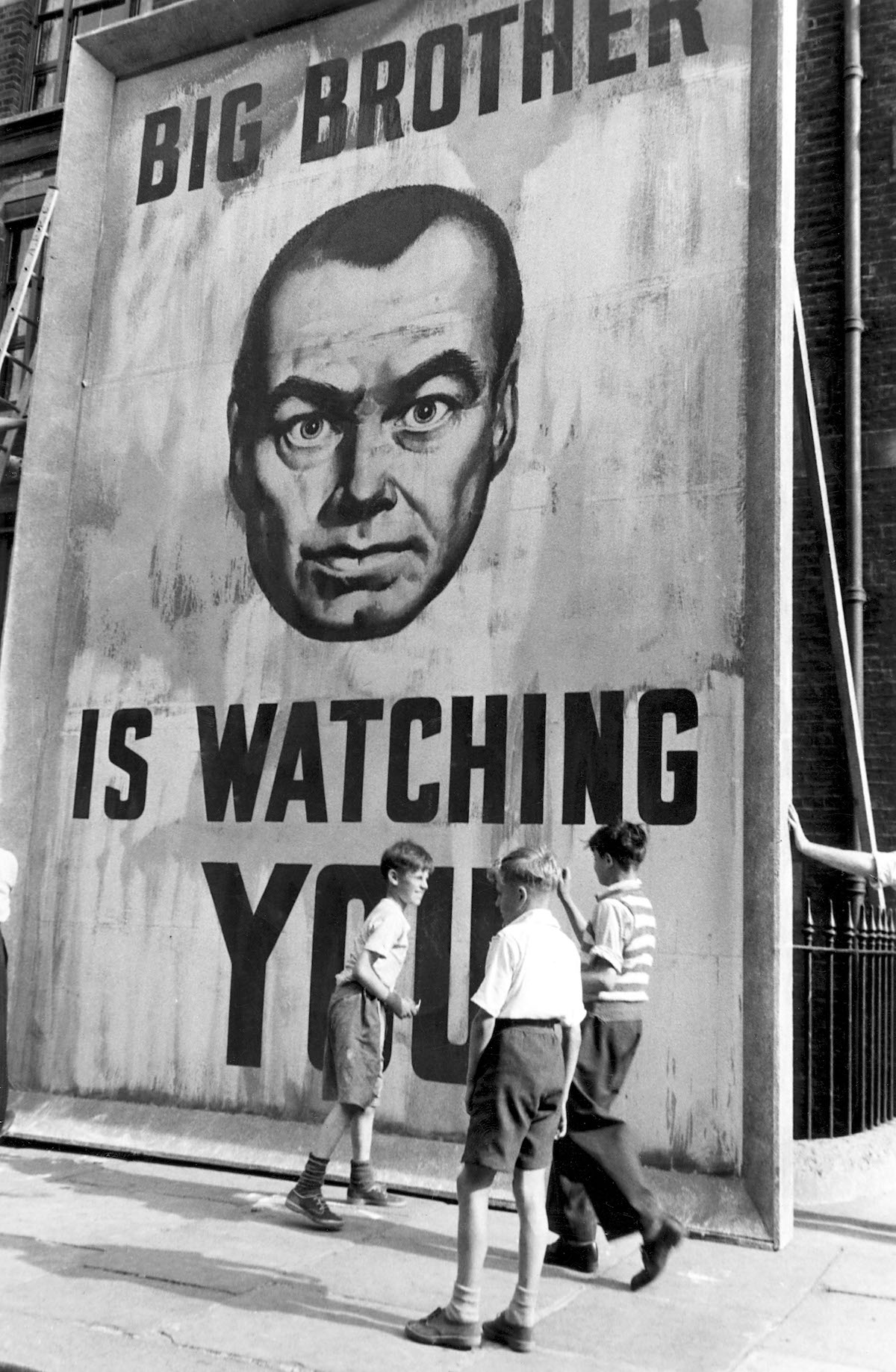

Orwell’s working title for Nineteen Eighty-Four, published on 8 June 1949, was ‘The Last Man in Europe’ – beleaguered isolation indeed. But the oppression of Winston Smith, its protagonist, is different: under totalitarianism there is no place even for secrets.

Intended as a rallying cry for individual liberty, Orwell didn’t understand early readers who found Nineteen Eighty-Four suffocatingly bleak. It was a satire, he said; its message was: ‘Don’t let it happen. It depends on you.’

Who was he addressing? Orwell’s faith in ‘the common man’ ran deep. Comstock eulogises ordinary people, in whom ‘greed and fear are mysteriously transmuted into something nobler’, and who retained ‘their standards, their inviolable points of honour’. Smith agrees: ‘If there is hope, it lies in the proles.’ Young men of England, awake.