The Myths and Realities of Ping-Pong Diplomacy

When the United States’ table tennis team was invited to China in 1971, the trip was about far more than sporting competition. Dubbed ‘ping-pong diplomacy’, it heralded a thaw in diplomatic relations between the two nations.

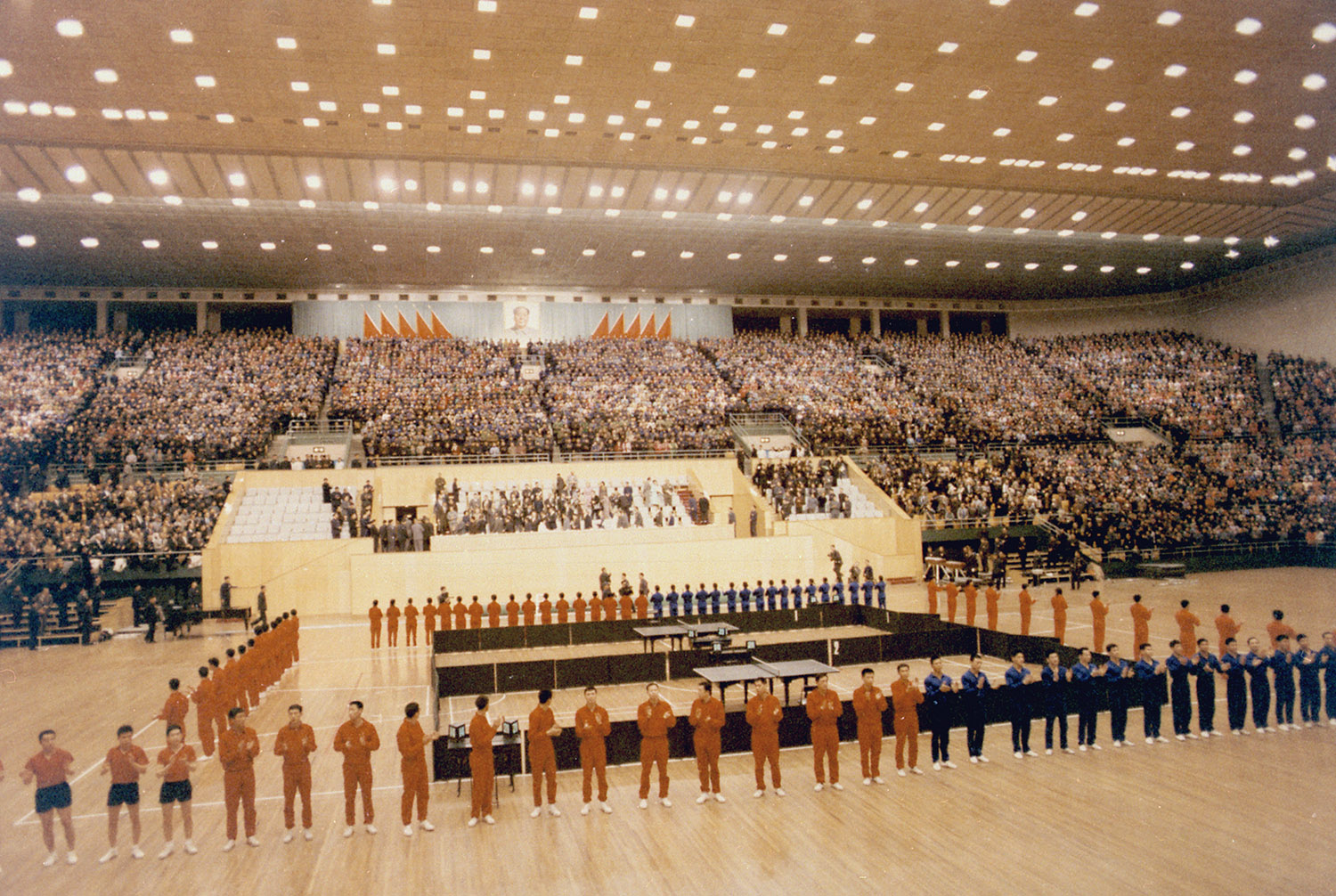

President Nixon attending a table tennis exhibition in Beijing, 23 February 1972.

In April 1971 a series of table tennis matches between the US national team and the world champions China made history. Then ranked 23rd in the world, the US team was comprised of amateur players, even paying their own expenses to travel to the World Table Tennis Championships in Nagoya, Japan where they first met their Chinese counterparts. The Chinese team’s superiority was clear: across the seven events at the Championships, they won four gold, three silver and two bronze medals. The Americans left empty-handed. Following the championships, the US team were invited to China for a short tour, where they had a chance to visit the Great Wall. On Premier Zhou Enlai’s orders, the Chinese prioritised ‘friendship first, competition second’, throwing a handful of the games. The tour, quickly dubbed ‘ping-pong diplomacy’ by the American press, was historic for its political, rather than its sporting, consequences.

After two decades of hostility between the governments of the two countries, fuelled by Cold War ideology and memories of the Korean War, the diplomacy brokered via table tennis soon led to visits to China by other, more prominent, Americans. They included National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger three months after the tour and President Richard Nixon less than a year later, as well as basketball players, physicists and the Philadelphia Orchestra. China sent an array of sporting and cultural delegations to the US, starting with their table tennis players.

One of the most frequently repeated myths surrounding the US team’s visit to China is that it marked the first time Americans had set foot in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) since its founding in 1949. Not only had Americans visited Communist China, some had lived there. Sidney Rittenberg, a former GI and a communist born in South Carolina, came to be the most prominent – and controversial – of the American ‘foreign friends’ who lived in China. These left-leaning ‘fellow travellers’ received favour from Chairman Mao Zedong’s government in exchange for their vocal loyalty to the regime. During the Cultural Revolution, Rittenberg was one of the most influential individuals at Radio Peking, then China’s equivalent of the BBC World Service, and his speeches were broadcast throughout China. His influence soon attracted suspicion, however, including from Mao’s wife Jiang Qing. Accused of being an American spy, Rittenberg was imprisoned in 1967 for more than a decade.

‘Ping-pong diplomacy’ is also sometimes referred to as the first time a group of Americans visited the PRC. Even this is not quite true: 41 of the 160 young Americans who travelled to the Sixth World Festival of Youth and Students, held in Moscow in 1957, continued on to China, where Zhou Enlai welcomed them as ‘pioneers in opening the contacts between the people of the two countries’. The visit received worldwide press attention, not least because the young Americans, many of them teenagers, were knowingly violating a US government ban on all travel to the PRC imposed in 1952. But their trip had little effect on diplomatic relations: the US State Department made good on its promise to seize the passports of the attendees and threatened to imprison any other Americans bold enough to follow in their footsteps.

What, then, was different in 1971? While another myth suggests that it was the ping-pong trip itself that restored communication between the two governments, in reality dialogue had continued throughout the Cold War. A series of ambassadorial-level negotiations between China and the US occurred from 1955 until 1970 in Geneva and Warsaw, with 136 meetings taking place. Often these talks reached a deadlock. This had been the case in 1957, when President Eisenhower had limited interest in a serious dialogue with Mao, fearing that any public initiative towards China would be met with hysteria from anti-communists in Congress.

By 1971 the situation had changed. Nixon, who had been Eisenhower’s vice president, had made it clear in a 1967 Foreign Affairs article that he no longer supported a policy of isolating China. Some contact with a country of a billion people had to be restored, he argued. Like Eisenhower, however, Nixon worried about a public backlash against any effort to negotiate with Beijing. When he and Kissinger opened a highly secretive backchannel to Mao and Zhou in 1970, they avoided using the White House letterhead for fear that Beijing would leak their correspondence.

Mao personally approved the invitation of the US table tennis players, overruling those in his Foreign Ministry, and even Zhou, who urged caution. Chinese documents reveal that the chairman’s decision was not without precedent: two months earlier, he had ordered that dozens of Americans should be invited to China over the course of 1971 and, crucially, that they could be drawn from across the political spectrum.

Like Nixon, Mao was open to diplomatic talks. He sought a rapprochement with the US, partly in order to deter an invasion of China by the Soviet Union, seemingly an imminent possibility after major Sino-Soviet border clashes in 1969. Mao also wanted to negotiate the end of the US military presence on Taiwan, which had protected the island since the PRC’s entry into the Korean War on the side of the North in 1950. Having pulled out of the secret backchannel with Washington in 1971 in protest at Nixon’s decision to bomb Cambodia, Mao used the table tennis invitation to signal that he had not given up on reaching out to the US.

Nixon was far less involved than Mao in ‘ping-pong diplomacy’. The president personally endorsed the State Department giving the US team permission to travel to China from Japan, but only on the condition that the US government would have no further involvement in the trip. In Washington, Kissinger worried that the amateur table tennis players might muddle his and Nixon’s delicate approaches to Beijing. Both were anxious about the public response to the team’s China trip; the overwhelmingly positive reaction of most ordinary Americans encouraged the White House’s diplomatic overtures to Beijing.

‘Ping-pong diplomacy’ was far from spontaneous, then. The Chinese team’s attendance at the World Championships was the first time the country had participated in an international sporting tournament since the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Beijing had been divided over whether to send their team to Japan, with hesitancy from both the players and the foreign ministry overcome by direct orders from Zhou and Mao. One reason behind the trepidation was fear: Chinese officials correctly predicted that the PRC athletes would face fierce anti-communist protestors in Japan. Mao told them to be ‘ready for death’ on their daring trip.

One important moment at the Championships did, however, occur by chance. American and Chinese players and officials had already conversed on the sidelines of the games in Japan. Graham Steenhoven, the president of the US Table Tennis Association, pointedly told his Chinese counterpart, Song Zhong, that Nixon had recently rescinded the ban on travel to the PRC violated by the 1957 youth delegation. But the breakthrough occurred when the US player Glenn Cowan boarded the Chinese team’s bus. An awkward silence was broken by the Chinese team captain Zhuang Zedong. As they got off the bus, Zhuang presented Cowan with a silk-screen depiction of China’s Huangshan mountains to rapid-fire clicks from gathered press cameras. Perhaps Zhuang had brought the gift to Japan to give to an American; perhaps it was just one of the tokens the Chinese carried for friendly interactions with rival teams. In any case, the interaction was a surprise to Mao back in Beijing. When he learnt of the incident via his digest of Western newspapers, he commented approvingly: ‘Zhuang Zedong is not only very good at ping-pong but also quite diplomatic.’ Soon, Mao sent word for Cowan and his teammates to be invited to China.

The Americans were not the only team to get such an invite. Teams from Colombia, Canada, Nigeria and the UK were all touring China simultaneously in April 1971. Nonetheless, the importance of US-China relations meant that Zhou told his closest aides that the Americans should be China’s top priority while in the country.

‘Ping-pong diplomacy’ did not end in 1971. Almost exactly a year later, the Chinese team arrived on a reciprocal second leg tour of the US. Though this was not the first time PRC citizens had visited the US, it was the first official delegation from Communist China.

The Chinese team played table tennis to 10,000 spectators at the Nassau Coliseum on Long Island and in the austere chambers of the United Nations. They visited Disneyland and Hollywood, as well as an African American church in Memphis and a car factory in Detroit. Zhuang Zedong told the Detroit factory workers that the Chinese players ‘salute the American working class’ and that they had ‘come to learn from you’. Whereas the Americans had been guests of the Chinese government, the Chinese team were received by two US non-governmental organisations: the US Table Tennis Association and the National Committee on US-China Relations. Nixon hosted the Chinese athletes at a White House Rose Garden reception.

In April 2021 China used the 50th anniversary of the American team’s visit to urge a return to the spirit that characterised the visit. ‘Ping-pong diplomacy’ has become a powerful example of cooperation trumping hostility – but we should take care to separate myth from reality as we invoke its memory. The 1971 breakthrough in US-China relations did not happen by chance. We should not hold our breath for another spontaneous ‘ping-pong moment’.

Pete Millwood is writing a history of how visits of athletes, musicians and scientists helped re-establish relations between China and the United States in the 1970s, to be published by Cambridge University Press.