The British Acquisition of Fiji

Traders and missionaries from Europe settled on Fiji many years before its official annexation by the British Empire.

The story of the British acquisition of Fiji throws light on the contrast between the British Government’s attitude to extensions of empire and that of British nationals. In Fiji itself there was the spread of European settlement, the conflict of interest between European and native, the problems facing British consuls and Fijian chiefs in their various attempts to impose order on a confused situation.

In Britain there was the clash of policies between a tight-fisted Treasury, a Colonial Office besieged by well-meaning humanitarians and a Foreign Office concerned with the wider context of international relations.

Over a period of fifteen years, between 1858 and 1873, successive British Governments opposed any extension of empire in the Pacific, while British subjects built up trade, missions and plantations. As for the Fijians, Consul Jones wrote in 1865: ‘in endeavouring to lead the South Sea Islanders on the path of progress, the chief difficulty is to find some motive to induce them to advance; it is not an easy matter to prove to them that it is for their advantage to adopt the civilization of the whites.’

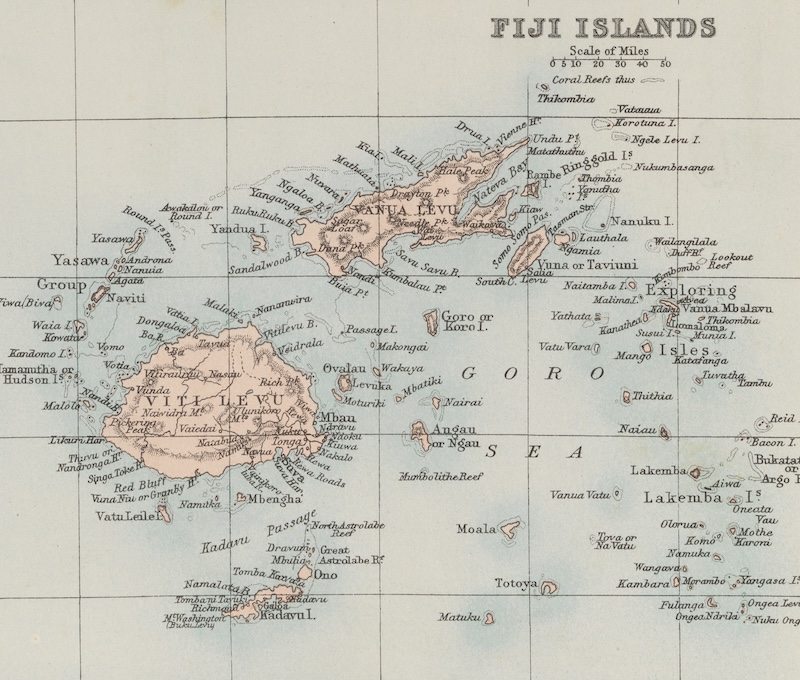

The 300 islands of the Fijian group lie across the 180th meridian, just below the 15th parallel. They fall into two parts: the western part contains the two largest islands of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu, and the eastern part the Lau islands. The inhabitants are classed as Melanesians, heavily influenced by Polynesian ruling families. ‘Incessant tribal skirmishing’ in the pre-European period produced continuous migration and resettlement.

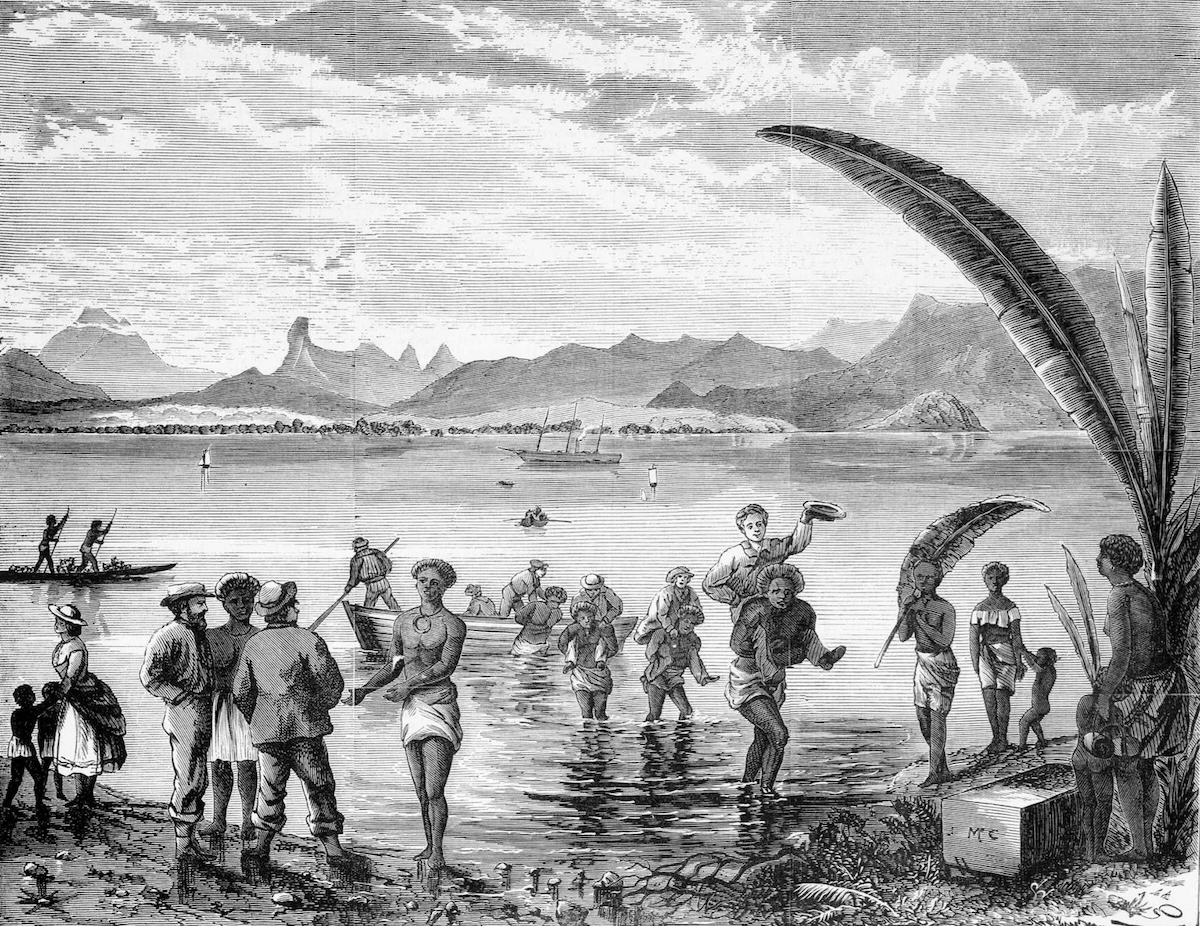

Islands of the group were sighted by Tasman in 1643, by Cook in 1774, and by Bligh in 1789. But European penetration of the islands did not begin until the early 1800s when the increasing traffic across the Pacific led to a trickle of beachcombers who settled among the coastal tribes.

Later came the traders: first the sandalwood merchants, who usually bought the wood (used by Polynesians to scent coconut oil, but especially prized by the Chinese) from tribal chiefs; then the beche-de-mer traders, seeking the grey-green sea cucumber, again for the Chinese market. This had to be dried before it could be shipped out of the islands and the trade led to the first semi-permanent European settlement.

The missionaries, Wesleyan, came in 1835, the first Europeans to introduce the concept of exclusive rights to land which became one of the problems of European settlement; they lived outside the Fijian villages in fenced properties, insisting on privacy and cleanliness for their families. Missionary influence spread slowly. The Fijians were preoccupied with tribal wars, particularly between the rival chiefs of Bau (a small island just off the east coast of Viti Levu) and Rewa (in the south of Viti Levu).

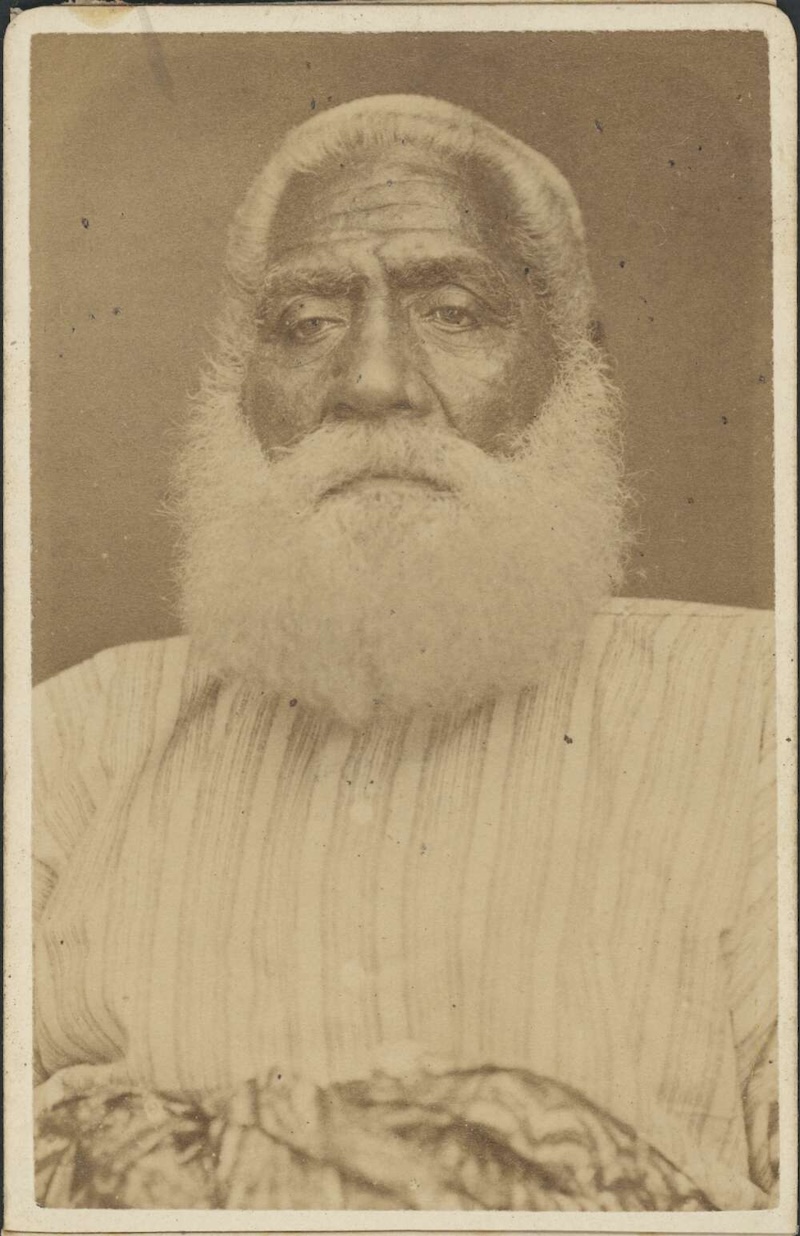

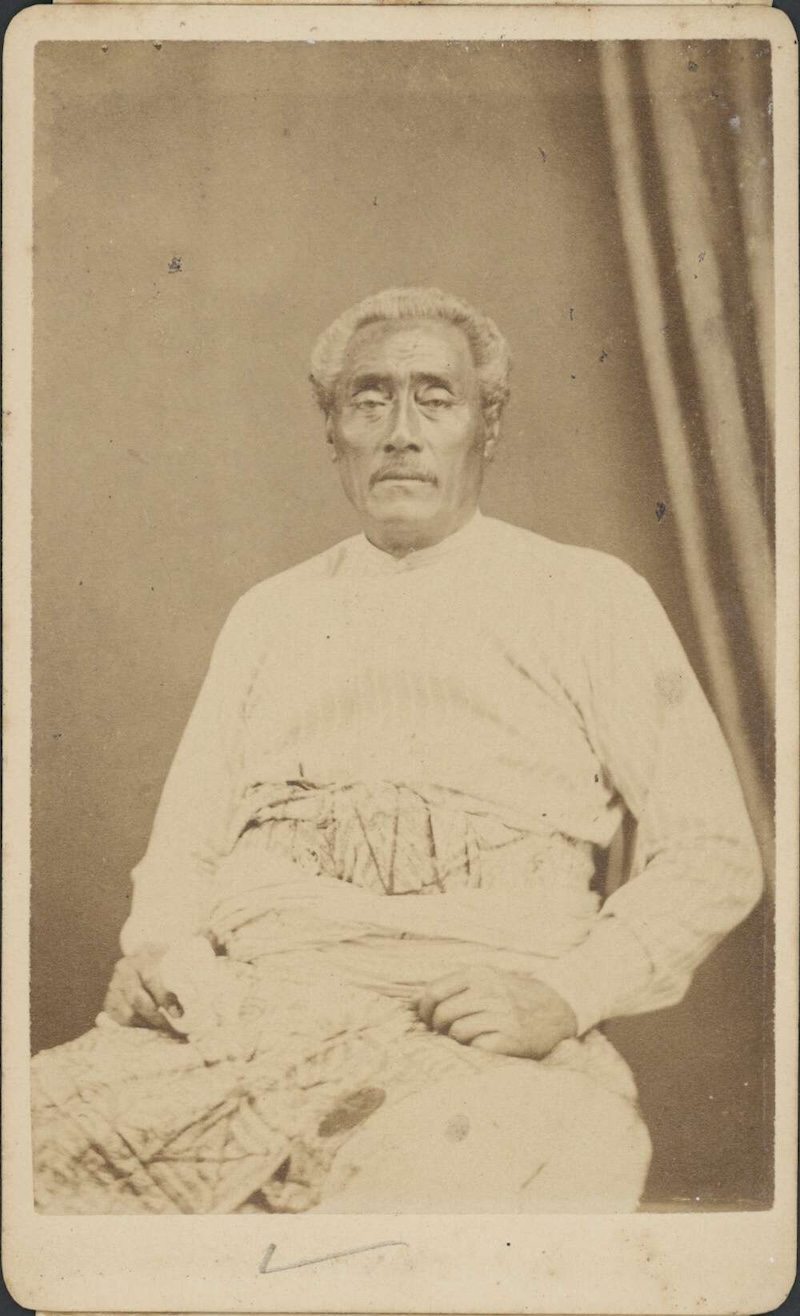

In 1854 the Bau chief Cakobau was converted to Christianity and in 1855 defeated his opponents with Tongan help. By 1860 there were three dominant chiefs in Fiji - Cakobau in Bau, Tui Cakau of Cakaudrove in Vanua Levu, and the Tongan Ma’afu in Lakeba and the Lau islands. Cakobau’s pretensions, after his victory, to be supreme ruler of Fiji foundered on Ma’afu, and the internal politics of the group tended to revolve between these two chiefs.

There were several European settlers by the 1850s and the main European settlement was at Levuka on Ovalau Island. A foretaste of possible problems occurred in 1851 when the house of the American agent, John Williams - who had arrived five years earlier from New Zealand and had bought vast acres of land - caught fire and was looted by local Fijians. Williams claimed $5,000 as compensation which was later increased to over $45,000. Cakobau was held responsible for the debt and was frightened into signing an acknowledgement.

By 1855, signs of French interest in Fiji had prompted one chief to write to the British Government asking it to annex the islands. On a more practical level, the New South Wales Governor, concerned with the security of communications, suggested the appointment of a consul in the area and in 1858 W. T. Pritchard arrived. No sooner had he set foot in Fiji when Cakobau, harassed by his American debt which he had committed himself to paying by the end of the year, offered to cede all Fiji to Britain.

Pritchard immediately returned to Britain with the offer. It was quite warmly received by Lord Derby’s Conservative Government which was, however, almost immediately defeated by Palmerston. Newcastle, as Colonial Secretary in the new Government, was mildly in favour of accepting the offer, mainly on the grounds of Fiji’s potential as a cotton producer.

But Gladstone as Chancellor of the Exchequer was opposed and Palmerston and Russell, as Foreign Secretary, were indifferent: the Pacific area was not a part of either the contemporary ‘colonial question’ or of Great Power relations. A Colonel Smythe was sent to report ‘whether it would be expedient’ for Britain to annex Fiji.

Smythe was delayed some time in New Zealand, then in the throes of land wars with the Maori, which seems to have had considerable influence on his assessment of the Fijian settlement. In his report he came out firmly against accepting Cakobau’s offer.

Cakobau, ‘although the most influential chief in the group, has no claims to the title of Tui Viti, or King of Fiji, nor would the other chiefs submit to his authority except through foreign compulsion’; his offer would only land Britain with yet more problems in the Pacific, Fiji would be no use to trans-Pacific shipping because of reefs and hurricanes, and its future as a cotton exporter, a project dear to Pritchard’s heart, backed by the Manchester Cotton Association, was insignificant.

It was too expensive and too hazardous, and Smythe recommended a form of ‘native government aided by the counsels of respectable Europeans’. Pritchard himself was later dismissed after a commission of inquiry into his land dealings, which he claimed were to encourage white settlement to develop the Fijian economy but which appear to have been rather less high-minded.

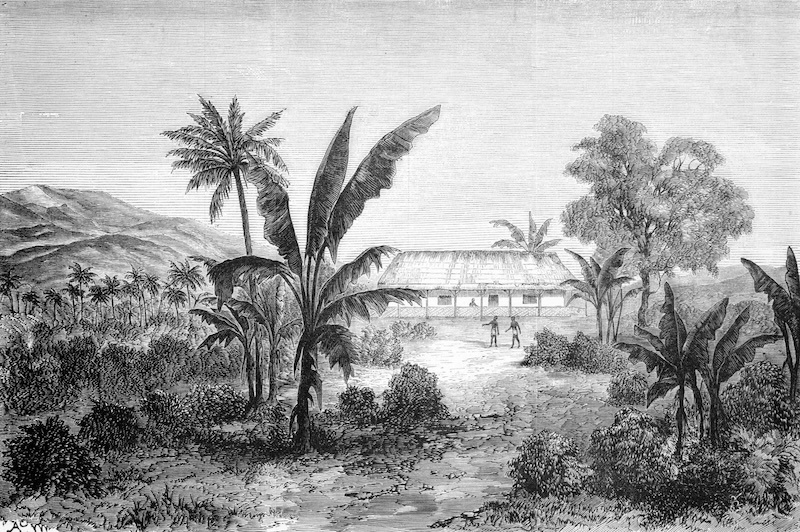

During the latter half of the 1860s the situation changed dramatically. The outbreak of the American Civil War led to a cotton boom in Fiji and a rapid increase in European settlement, helped also by the Australian depression at the end of the decade. There was little attempt to regulate land sales and Fijians alienated large blocks of land with no conception of what they were doing.

The fact that Europeans at first offered so little for land did not encourage Fijians to value the ‘sales’ so much as the Europeans. Moreover, the Fijian practice of shifting cultivation made tribal property difficult to define; European purchasers were inclined to disregard customary claims to the land which were often time-consuming to unravel.

British consuls, from Pritchard onwards, tried to remedy the situation and prevent the inevitable racial discord that would arise from uncontrolled land sales. Their task was made greater by the absence of instructions from Britain and of any constituted authority with which they could draft regulating treaties.

Pritchard was the first to draw up rules for the alienation of land which he hoped would be clear to the Fijians, but he had no machinery for investigating the deeds of sale brought to him as consul for registration, and his own purchases discredited him in the eyes of the Fijians. A successor, H. M. Jones, who arrived in 1864, tried to regulate land proceedings according to English law and wrote asking for copies of relevant statutes, but they did not reach Fiji until 1866 when he was on the point of leaving.

Similar attempts to control land sales were made by a series of native governments set up during the 1860s and early 1870s in various parts of Fiji, often where the chiefs were influenced by European secretaries. Cakobau’s first and quite ineffective effort, prompted by Jones, was made in 1865; his second, the establishment of the Kingdom of Bau in 1867, with the backing of European settlers and the assistance of his secretary, W. H. Drew, was little better; what authority it did have was undermined by the failure in 1868 of an expedition to punish the highland murderers of a Wesleyan missionary.

A more effective government was constituted by Ma’afu in Lakeba, with the help of his secretary R. S. Swanton, who introduced legislation to regulate land sales to Europeans. Cakobau’s failure to see the dangers of large-scale land sales was demonstrated in 1868 when he signed an agreement, later invalidated, with an Australian group, the Polynesia Land Company, which undertook to pay off his American debt in return for 200,000 acres which were not his to bestow.

In 1871 a group of Levuka settlers persuaded Cakobau to set up a government under the 1867 constitution, with several Europeans from Levuka as his ministers. The consul, Edward March, was not consulted, nor were the planters, let alone the Fijians. But with the exception of March most Europeans, of whom there were now about 1,700, and most chiefs - including Ma’afu - came to acknowledge Cakobau’s government. Once again, its authority was limited to the coastal areas of the main islands and it operated largely in the European interest.

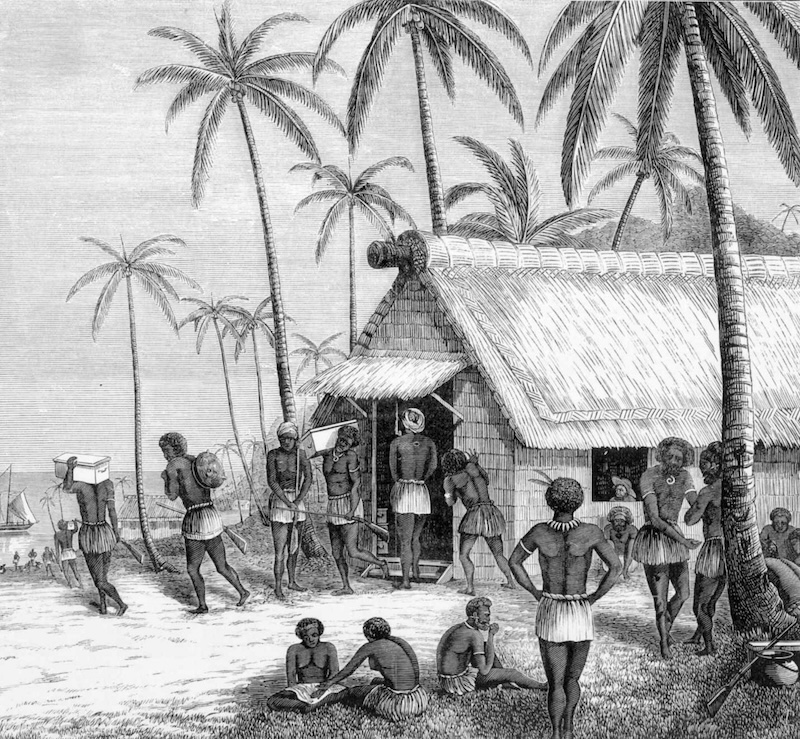

Although in Fiji itself it was the land crisis that came increasingly to bedevil relations between Europeans and Fijians, British public opinion was aroused to concern with Fiji only over the labour trade - the transportation of labourers from other islands, especially the Solomon Islands and the New Hebrides, to work on European plantations. Among the planters the Fijians had at first been highly regarded as workers: ‘they are willing to labour when they can count upon reaping the fruits of their labours, which they rarely can under the Chiefs’, wrote a settler in 1859.

Many of those who came in the later 1860s, however - from Australia and New Zealand for the most part - were often profoundly influenced by racial opinions in those countries. This changed attitude of the settlers towards the Fijians, the Fijians’ own distrust of the purchasers of their land and the basic inadequacy of the labour supply led to the labour trade.

The idea of moving islanders from one part of the Pacific to another to help develop European economic interests was no novelty. One of the earliest examples was in 1847 when an Australian, Benjamin Boyd, recruited some New Hebrideans for his New South Wales sheep station. In 1863 Robert Towns, formerly a sandalwood merchant, imported islanders, known as kanakas, for his Queensland sugar plantation.

The same year the particularly abusive Peruvian labour trade, which depopulated several Pacific islands for the guano islands off the Peruvian mainland, aroused the outside world to abuses elsewhere, especially in the recruitment and transport of the islanders. Queensland introduced a licensing system in 1868, but there were few means of enforcing it and in several Melanesian islands missionaries reported the social and economic disruption of villages whose male populations had been drastically reduced.

Mark Twain had a nice comment on the missionaries’ opposition to the labour trade: ‘but for the meddling philanthropists the native fathers and mothers would be fond of seeing their children carted into exile and now and then the grave, instead of weeping about it and trying to kill the kind recruiters’.

In Fiji native labourers were first imported in 1864. The disinclination of the Fijians to plantation work combined with the cotton boom greatly to increase the trade. This was supervised unofficially and inadequately by the British consul.

The trade was mostly carried on by British subjects in British ships, which the consul registered, but he had no means of determining how willingly the islanders came. March reported to the Foreign Secretary, Clarendon, in 1869 that the islanders were generally well treated in Fiji but there was no control over the manner of obtaining them.

As early as 1865, when the Foreign Office first suggested that the consul’s powers should be extended to cover jurisdiction over British subjects, the Treasury commented that, if a jurisdiction were created, courts would have to be established which the British Government would be obliged to support financially as well as morally.

Equally there was the point made by Clarendon in 1869 that ‘unless effective measures are speedily taken to regulate, if not to prohibit (the labour trade) Her Majesty’s Government will experience the mortification of seeing a systematic slave trade breaking out in a new quarter’.

There was also the problem that the consul’s powers could only be extended by treaty with a recognized authority and this, despite Cakobau’s claims, was obviously not there. In 1870 Consul March issued regulations for the trade which foundered, mainly because of March’s own bad relations with the British in the area, but also because he had no power to enforce them.

In 1871 Cakobau’s new government assumed responsibility for the labour trade and passed regulating legislation which it was unable to enforce, while the British Government refused to recognize his government until it could show that it could enforce them.

In 1871 the murder of Bishop Patteson (who had justly commented that ‘it is very difficult for even well-intentioned men to carry on this trade honestly’) in Nukalau in the Santa Cruz group, in revenge for the forcible recruitment of labourers, emphasized the need for establishing control in the Pacific generally.

The Pacific Islanders Protection Act was passed in 1872, full of good intentions but virtually unenforceable. Within Fiji itself a financial crisis in 1873-4, after the end of the cotton boom, meant that many imported labourers were either unpaid or were un-returned to their islands at the end of what was usually a three-year contract.

The arguments for the cession of Fiji in 1858-60, when Smythe investigated the offer, had been mainly strategic and economic and were rejected by Smythe on these grounds. Gladstone as Prime Minister was still opposed to annexation when the issue was revived in 1869 mainly on humanitarian grounds, as was the Colonial Office.

When the Foreign Office pointed out the possibility of American annexation, a Colonial Office official remarked: ‘Is the fear of the United States to make us entangle ourselves in Fiji?’ and the Government discussed trying to persuade another power to take on the burden - Belgium or the North German Confederation. Gladstone told Kimberley he hoped nothing would be done ‘which will lead us into responsibilities unawares – as in New Zealand – and in Abyssinia’.

The driving force for annexation came predictably from the humanitarians, in particular the Aborigines Protection Society and the Anti-Slavery Society. The humanitarian approach had changed slightly since the 1830s when missionary influence during the debate on the annexation of New Zealand argued that the natives must be preserved from European contact. Now they argued that the British presence in Fiji must benefit the natives and that difficulties between European and native were the result of lawlessness rather than the impact of one culture upon another; they objected not to the labour trade and the alienation of land, but to the abuses thereof.

In 1872 Disraeli made his celebrated speech in the Crystal Palace, in which he demanded a positive response ‘to those distant sympathies which may become the source of incalculable strength and happiness to this land’. The next day he was quoted by William McArthur, one of the most vociferous spokesmen of the humanitarians in Parliament, and head of a firm with Australasian interests, when he moved in the House of Commons the annexation of Fiji ‘in the interest of Christianity, commerce and liberty’. Gladstone in the same debate, however, frequently drew attention to mistakes made in New Zealand.

There were obvious obstacles to annexation. In 1871 the Colonial Secretary, Lord Kimberley, wrote to Lord Canterbury, Governor of Victoria - the Australians were as anxious as the humanitarians for annexation, but were loath to pay for it themselves - that ‘the islands are under the jurisdiction of several chiefs and even if they all concurred in an Act of Cession to the Queen, the experience of other Colonies shows that disputes would be sure afterwards to arise, especially as to the occupation of land by the settlers’.

New Zealand was undoubtedly in his mind, and the likelihood of his being correct was borne out by the acting consul, Thurston, who wrote in 1873 of parliamentary government in Fiji being reduced to a farce over the issue of land: ‘the whites look upon Fiji as their domain, and upon Fiji men as husbandmen to till it’.

In a rather mournful exchange the same year Gladstone refused ‘to be a party to any arrangement for adding Fiji and all that lies beyond to the cares of this overdone and overburdened Government and Empire’. To which Kimberley replied: ‘I take a more sanguine view I confess of the power and energy of this country than you do’. And Gladstone: ‘It is quite right you should be more sanguine than I, for I am old and begin to feel it’. Yielding to the pressure of public opinion, however, he reluctantly agreed to send a commission of inquiry to Fiji.

The Commission consisted of E. L. Layard, newly appointed consul in Fiji, and Commodore James Goodenough. They were to investigate the situation in the light of four possible courses of action - a take-over by force, recognition of the existing government, the establishment of a protectorate, or outright cession.

They were warned that the Government was ‘not only far from desiring any increase of British territory, but would regard the extension of British sovereignty to Fiji as a measure which could in no case be adopted unless it were proved to be the only means of escape from evils for which this country might be justly held to provide an adequate remedy’.

It was vastly preferable that Fiji should have its own indigenous government ‘than that this country should assume the heavy responsibility of governing a dependency inhabited by a large native population at the other side of the globe’ - the New Zealand lesson had been well learnt.

In their report, Goodenough and Layard emerged heavily on the side of annexation as the only means of resolving the anarchy, so much so that they accepted an offer of conditional cession from Cakobau, to the dismay of the new Conservative Government - Gladstone had been defeated in 1874. Contrary to expectation, Disraeli’s Government was by no means eager for cession.

‘Very bad and dangerous terms’, commented Carnarvon, the new Colonial Secretary, when he read of Cakobau’s conditions, which included the retention of ‘private rights’ for Fijian chiefs. The strongest reason for annexation was the likelihood that anarchy in Fiji would ultimately involve the Government in more trouble and expense. The Governor of New South Wales, Sir Hercules Robinson, was despatched to Fiji to see if Cakobau and his fellow chiefs would agree to unconditional cession.

Cakobau agreed after a little hesitation, remarking that ‘if matters remain as they are Fiji will become like a piece of driftwood on the sea and be picked up by the first passer-by’. Sir Hercules wrote drily: ‘I am sorry to say that all experience teaches us that when white men settle down in a place of this sort the natives are unable to protect themselves until some strong civilized Government is established’. Thus Fiji became British in 1874. In Britain the news was received with great enthusiasm and Kimberley wrote to Gladstone: ‘It is curious that John Bull is not cured of earth hunger by this time’.

Sir Arthur Gordon’s establishment of a colonial administration is really another story. But to complete that of the acquisition of Fiji, it is worth mentioning briefly the measures taken to settle the two main problems leading up to acquisition - land and the labour traffic. Gordon, a most remarkable and in some ways thoughtful administrator, made the maintenance of chiefly authority the backbone of his land policy.

He prohibited further land alienation and vested most of the remaining unsold land in the Fijian community. He has been criticized for making too much of virtually non-existent Fijian traditions, basing his policy on what he alleged was the traditional inalienability of land; he maintained that Fijian society was governed by a series of ‘rigidly observed laws’ when this was far from being the case, and institutionalized these customs, thereby hampering the islands’ development and causing dissatisfaction.

He also imposed restrictions on the employment of Fijian labour, at the same time killing the Pacific labour traffic in Fiji with the far more efficient system – which he had already used when Governor in Mauritius and Trinidad – of indentured Indian labour; the Indian coolie was more expensive to introduce, but he was more adaptable and there was an ample supply.

As far as the labour trade in general was concerned, Gordon’s appointment to Fiji was extended a year later to include the consulate-general of the islands of the South Pacific, in the hopes that he would be able to stop the abuses where they were most likely to occur - in recruiting and transhipment. Disagreements between the Colonial Office and Foreign Office as to who should control the consular officials appointed to the area postponed more effective legislation.

Finally in 1877, the Western Pacific High Commission was set up, covering the Samoan, Tongan, Union, Phoenix, Gilbert, Ellice, Marshall, Caroline, Solomon, Santa Cruz and Louisiades Islands, Rotuma, New Guinea, New Britain, New Ireland ‘and all other islands in the Western Pacific Ocean’ not already controlled by anyone else. Its headquarters was in Fiji and Gordon was the first High Commissioner. It was a clumsy piece of machinery, and in many ways ineffective since it was partly dependent on political conditions in the various islands.

The Pacific labour trade and its abuses died out by the end of the century, not so much through legislation as through lack of demand. Nevertheless, the Western Pacific Commission was seen as a genuinely philanthropic effort to remedy one of the worst results of European penetration of the area. In accepting the responsibility for Fiji in 1874, the British tried, with some success, to compensate for their earlier disregard of the consequences of the invasion of a primitive civilization by 19th-century capitalism.