Jane Austen: A Partial and Prejudiced Historian

On the 250th anniversary of her birth, Jane Austen still has lessons for readers of history.

Henry IV ascended the throne of England much to his own satisfaction in the year 1399.

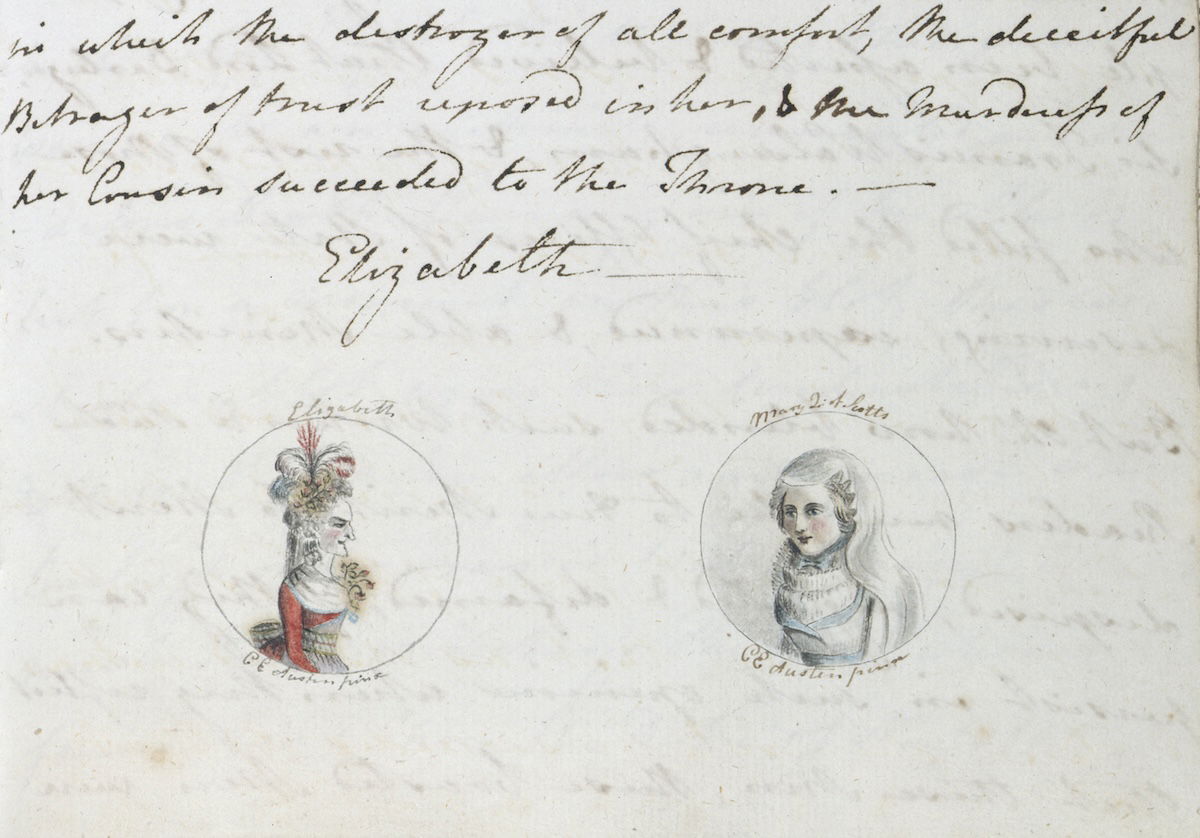

As opening lines for a history go, this is an excellent one. Its author was the teenage Jane Austen, in a lively short piece she wrote for the entertainment of her family: The History of England from the Reign of Henry IV to Charles I, by – as Austen gleefully proclaims herself – ‘a partial, prejudiced and ignorant historian’.

This year is the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth, and events celebrating her life and work are taking place across the country. It is a good opportunity to remember that Austen was not only an innovative novelist, but also a sharp and thoughtful reader of history, as well as a satirist of the historians of her day. Though she was only 15 when she wrote her History of England, the wit of her later novels is unmistakably present. No one but Austen could have written of Edward IV that he ‘was famous only for his beauty and his courage, of which the picture we have here given of him, and his undaunted behaviour in marrying one woman while he was engaged to another, are sufficient proofs’.

Austen promises that her history will contain very few dates. Its purpose is not to give information, but ‘only to vent my spleen against, and show my hatred to, all those people whose parties or principles do not suit with mine’. She is shamelessly partisan: pro-Yorkist, anti-Tudor, and an outspoken fan of Mary, Queen of Scots. She defends Richard III and Anne Boleyn, but attacks ‘that disgrace to humanity, that pest of society’ Elizabeth I. Mischievously (for the daughter of an Anglican clergyman), she is proud to announce her sympathy for Roman Catholicism. Her audacious exaggeration and total lack of impartiality are delightful, but also reflect the teenage Austen’s keen perception of the implicit prejudices in the histories she had read – just as biased, she suggests, if more subtle in conveying their authors’ opinions.

Questions about the historian’s art are also explored in Northanger Abbey, through a conversation between the heroine Catherine and her friends Eleanor and Henry Tilney. All three are enthusiastic readers, but Catherine, though a lover of novels, confesses that ‘history, real solemn history’, is not to her taste. It is all tiresome, ‘the quarrels of popes and kings, with wars or pestilences, in every page; the men all so good for nothing, and hardly any women at all’. Innocently assuming that everyone finds reading history as boring as she does, Catherine pities historians, who work so hard to write books that no one enjoys: ‘Though I know it is all very right and necessary, I have often wondered at the person’s courage that could sit down on purpose to do it.’

Catherine is an unworldly character, and her naivety is comic – but she is far from stupid, and through this conversation Austen explores some genuine questions about the historical writing of her time. Catherine’s observation about the priorities of male-dominated ‘solemn history’ might well echo the feelings of the young Austen, who chose to devote the most space in her History of England to two women, Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots.

The other issue raised in this discussion is about the relationship between history and imagination, and how far the historian’s task might overlap with that of the novelist. Catherine cannot understand why she finds history boring when it must be as full of invention as the Gothic novels she does enjoy. Since historians have to use their imagination to elaborate on the thoughts and motivations of their characters, she wonders, why isn’t the result more entertaining? Eleanor Tilney, a wiser reader than her friend, defends the historians. She enjoys reading history, because she is able to appreciate these inventions as examples of literary skill; it is the reader’s responsibility, it is implied, to be alert to the blend of fact and imagination in historical writing. To Eleanor history is an art, not merely a duty, so she can take more from it than poor Catherine.

Northanger Abbey is very much about learning to be a discerning reader, taking pleasure in the works of the imagination without forgetting to apply reason and judgement. This conversation suggests that challenge applies just as much to reading history as to Gothic novels. Whatever we might think of the writers of history – partial and prejudiced, or labouring over unread books – Austen reminds us that readers of history have our responsibilities too.

Eleanor Parker is Lecturer in Medieval English Literature at Brasenose College, Oxford.