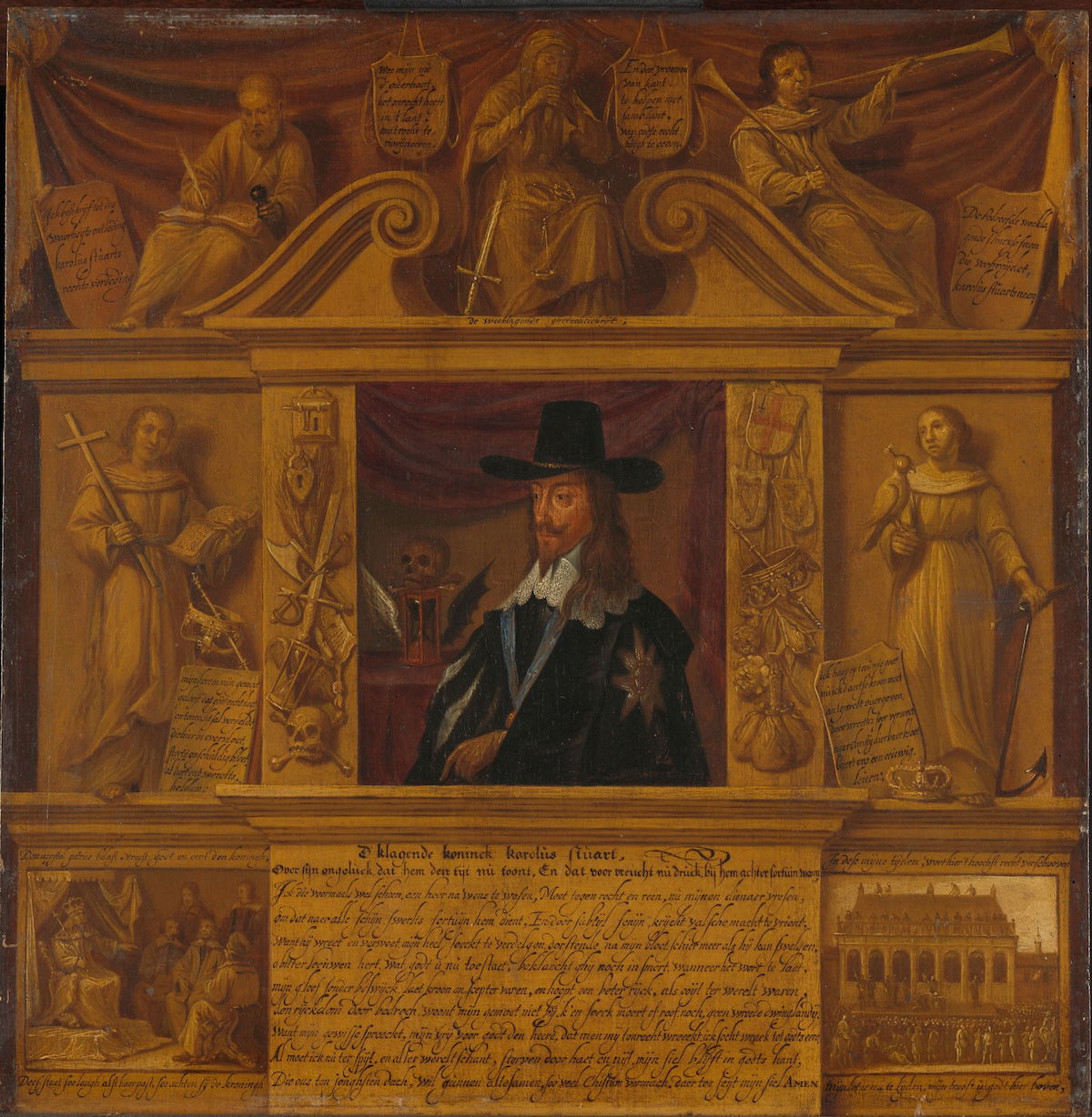

Did Charles I Have to Die?

King Charles I’s execution in 1649 turned the world upside down – were other outcomes possible?

‘The king’s guilt was not in doubt’

Alice Hunt is Professor of Early Modern Literature and History at the University of Southampton and author of Republic: Britain’s Revolutionary Decade, 1649-1660 (Faber and Faber)

The technical answer is ‘yes’. Charles was charged with, and found guilty of, levying war against his Parliament (which represented the people) and of a ‘wicked’ design to rule according to his own will. Treason had been redefined to encompass a king waging war on Parliament. Accordingly, the trial’s commissioners – who acted as both jury and judges – sentenced this ‘tyrant, traitor and murderer’ to death ‘by the severing of his head from his body’.

But the trial rested on unprecedented legislation. Earlier in January, when the House of Lords rejected the bill that would bring this novel High Court of Justice into being, the Commons responded with the astonishing declaration that the people were ‘the original of all just power’ and that the Commons (as the people’s representatives) held ‘the supreme power in this nation’. They could pass laws without the king’s consent, or that of the Lords. Charles refused to acknowledge this, or the court’s authority. He was not the only one. Many of the summoned commissioners never took their places. Thomas Fairfax, leader of the New Model Army, did not attend any of the public sessions.

In addition, the parliament that had pushed through this legislation was the ‘Rump’ parliament. During the last weeks of 1648, while MPs were still trying to negotiate with Charles, powerful figures in the army (Henry Ireton and, eventually, Oliver Cromwell) declared that the king was ‘the capital and grand author of our troubles’ and that he should be ‘brought to justice for the treason, blood and mischief he is therein guilty of’. Many soldiers also believed that, because they had been victorious on the battlefield, God himself had declared against Charles. For them, the king’s guilt was not in doubt. The question was how to get Parliament to stop treating with Charles, and bring him to account. The army’s answer was to forcibly purge Parliament of any wavering MPs.

In these circumstances, once this trial went ahead, most knew that it could, and would, end with the king’s death. Charles himself prepared for martyrdom. He refused to plead either guilty or not guilty, which was tantamount to accepting a guilty verdict. In this sense, to save what he believed a king was, Charles ‘had’ to die.

‘Reformists believed Charles couldn’t be trusted’

Jonathan Healey is Associate Professor of Social History at the University of Oxford and author of The Blood in Winter: A Nation Descends, 1642 (Bloomsbury)

Charles I’s rule collapsed for two reasons, both crucial to understanding the civil wars. One was religious: he was a High Church anti-puritan, and this alienated much of England and caused revolution in Scotland. The other was constitutional: he took taxes without his English Parliament and used the judiciary to rule by royal prerogative. When the crisis came between 1640 and 1642, Charles caved on much of this. He allowed his power to crumble in Scotland, while in England he conceded regular parliaments and an end to prerogative taxes. He changed direction on the Church and moved towards the centre ground.

But he never traded his powers willingly, and was always looking for ways to regain control – by hook or crook. He tried to suppress the Scots by force twice, and engaged in a series of plots against reformers both in London and Edinburgh. When rebellion broke out in Ireland in late 1641 many reformists had come to believe that Charles couldn’t be trusted to control an army, or even the county militia used for defence. Nor, even, should he be allowed to appoint his own government officials. Charles believed, correctly, that the reformists wished to strip him of most of his powers. His enemies believed, correctly, that Charles wanted to regain the upper hand and get revenge. War was unavoidable.

There were those who sought desperately to bring the two sides to an ‘accommodation’, but ultimately they were irreconcilable. When fighting came, both sides could make a legitimate claim that the other had started it, but the reality was a deathly spiral.

Parliament won the war, eventually. Charles would have to accept defeat and a dramatic curtailing of his monarchical powers, likely a permanent one. This would have saved his rule and his life, but he chose another path. Playing off one victorious faction against another, he refused a treaty and started another war. Defeated again, he once more negotiated, but understandably the more radical parliamentarians had lost all remaining trust in their king. By late 1648 those radicals had decided that Charles had to die, and it was they who were now making the decisions.

‘Charles’ execution was not a foregone conclusion’

John Rees is Author of The Fiery Spirits: Popular Protest, Parliament and the English Revolution (Verso)

Outcomes are never inevitable, but choices made in one timeframe can become objective limits in the next. Charles’ regime was in a state of existential crisis from the late 1620s. It faced riots, rebellions, a tax strike, and the assassination of the duke of Buckingham. This was followed by the forcible dissolution of Parliament and the imposition of 11 years of personal rule and, in 1640, war with Scotland. When, in 1642, the king was forced from his capital, he chose military action, precipitating civil war. His execution was not the foregone conclusion of his defeat in 1645, but it was certainly another step closer.

Many parliamentarians would still have preferred an accommodation with the king, including Oliver Cromwell. But two civil wars had created a radical political constituency in the New Model Army, in London, and among a minority of MPs. The king remained adamant that he would accept no settlement but a return to his old powers – a settlement unacceptable to the newly radicalised parliamentarians.

The ‘fiery spirits’ in the Commons included Henry Marten, Thomas Rainsborough, Alexander Rigby, and William Strode. With the exception of Marten, they had not been republicans before the Long Parliament, but a decade of revolution and war had made them so. When war came they were foremost in raising men, money, and munitions to fight the king until Parliament pushed aside its moderate commanders and achieved a crushing victory. By 1647 they had a considerable following among both the officers and the rank and file of the New Model Army and among the supporters of the Levellers, then at the height of their power.

The old political centre ground that favoured reviving the traditional constitution of king, Lords, and Commons could not hold. This polarisation, set in stone by ‘Pride’s Purge’, when moderate MPs were excluded from the Commons in December 1648, made the execution of the king highly probable. Once the king’s trial began, reprieve was always the least likely outcome, even if it was still desperately hoped for by many. It would be Marten – the fiercest of the ‘spirits’ – who signed the king’s death warrant in January 1649, designed the seal of the new republic, and was given the task of disposing of the late king’s possessions.

‘The answer depends on how we define “kingship”’

Rachel Hammersley is Professor of Intellectual History at Newcastle University

The question posed here is deceptively simple. I have 350 words, yet surely only one is required: either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. But history is rarely so straightforward. We have to ask: is the question concerned with whether any king ruling these islands at that time would have had to die? Or, is it about whether this particular king, Charles I, had to die?

The answer to the first question appears to be ‘no’. There were few open opponents of kingship in England prior to 1649. Henry Marten and Thomas Chaloner fit this category, but most MPs continued to advocate working with Charles even after his defeat in the civil wars. One could, of course, question how far it was prudent to argue against kingship at that time, so perhaps there were opponents who kept quiet, but the demands made by parliamentarians between 1640 and 1648 were not inherently incompatible with kingship. Rather, they sought to shift the balance of power from king to Parliament. Documents such as the ‘Nineteen Propositions’ (June 1642) and ‘Newcastle Propositions’ (July 1646) called for: parliamentary approval of royal counsellors, office-holders, and Peers; parliamentary control over the royal children; parliamentary oversight of the military; and the implementation of Parliament’s proposals for Church reform. It was, therefore, possible to imagine a system in which the king continued to rule but with more limited powers.

But, from this, we might conclude that the answer to the second question is ‘yes’. Charles did have to die because he was unwilling to accept those restrictions on his power. ‘His Majesties Answer to the Nineteen Propositions’ declared that agreeing to those propositions would effectively transform him into ‘a duke of Venice’ and England into ‘a republic’.

Does this, though, require us to reconsider our answer to the first question? Kingship, as Charles understood it, was plainly incompatible with Parliament’s demands, so it could be argued that it was necessary for the king to die in order to secure the kind of regime MPs were seeking. In part, then, the answer depends on how we define ‘kingship’ – and whose view we adopt.