From Greece to Gettysburg: Edward Everett, American Patriot

Best known for being upstaged by Abraham Lincoln at the Gettysburg Address, Edward Everett was also the first American to receive a PhD and a classicist who became an unlikely spokesperson for Greek revolutionaries.

Edward Everett (1794-1865).

It is astonishing to think that when, in 1821, Greece declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire, its first appeal to America for recognition and support was not to the US government, but to a classicist. Yet, after the Greek War of Independence broke out in February 1821, a phenomenon which the US press dubbed ‘Greek fever’ or ‘Greek fire’ swept across the nation. Few fanned the flames as much as Edward Everett, who, as the first American point of contact for the revolutionaries, led the charge on behalf of the Greeks in America.

Like many of the dead Greeks and Romans he admired most, Everett tends to be described as an ‘orator and statesman’. Born in 1794, his lifetime spanned the presidencies of George Washington to Abraham Lincoln, and the 14 heads of state between. During his career, he held a number of political offices, including Governor of Massachusetts, senator and disappointed vice presidential candidate. For his oratorical skill he was more than once called the ‘Cicero of America’. Yet during his long career he wore many more hats: of minister, traveller, scholar, editor, educator and diplomat.

Today Everett is best remembered for the speech he gave at the National Cemetery at Gettysburg on 19 November 1863. There, the 69-year-old Everett’s two-hour oration (delivered as the ceremony’s top-billed speaker) was overshadowed by Lincoln’s 272-word Gettysburg Address, which lasted a little over two minutes and finished before the photographer had time to set up his camera. In a letter that Everett wrote to the president the next day, he confessed, perhaps with some embarrassment, ‘I should be glad if I could flatter myself, that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes.’

Yet there is a chapter of Everett’s life – decades before his last national hurrah at Gettysburg – that is largely overlooked in the United States. As a young man, Everett was appointed to the first named professorship of Greek at Harvard. He became the second American traveller (after the Philadelphian Nicholas Biddle) to record a journey through the Ottoman Empire and was the first classical scholar to combine his academic pursuits with activism on behalf of the Greek people and the cause of Greek independence.

In January 1813, the 18-year-old Everett published what seems to have been the first American contribution to scholarship on modern Greek literature, an essay in The General Repository and Review titled ‘On the Literature and Language of Modern Greece’. The piece brimmed with typical commonplaces: laments over the corruption of the Greek ‘dialect’, coupled with hopes for the restoration of a purer ‘Attic’ form. It included a catalogue of noteworthy modern books in Greek, but Everett was writing from Massachusetts and modern books printed in Greece were sparse on his side of the Atlantic. He concluded his essay on a note of frustration:

We regret that this is all the information which we have been able to collect on the modern Greek language and literature. Though there have been written many books, from which we might expect the most interesting details upon this subject, we have been generally disappointed […] Our greatest obligations are to the notes and appendix of Lord Byron’s new poem of Childe Harold.

Probably inspired by Byron, Everett also wrote into his essay expressions of hope for Greek freedom, a theme he would soon reprise when he spoke in October at Harvard’s 1813 commencement exercises, where he took his Master of Arts. ‘On the Restoration of Greece’, the oration he gave on that occasion, is lost, but its subject was Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire.

The following year, in 1814, Harvard received a gift from an anonymous benefactor – later revealed to have been the Boston banker and merchant Samuel Eliot – to establish a professorship of Greek literature in honour of his son Charles, a Harvard graduate who had died from tuberculosis aged 22 in 1813. The bequest was unusual in that it stipulated a professorship in Greek literature, for, while instruction in Greek and Latin had been the centrepiece of US college curricula since the early 17th century (Harvard was founded in 1636), lessons had tended to follow Oxbridge models and consisted primarily of hours of closely supervised grammatical drilling.

Everett was the clear candidate for the new position and, on 12 April 1815, aged 21, he gave up his ministry at Boston’s Brattle Street Church and assumed the post. He accepted the position on a condition: that he would first be granted two years’ leave to travel in Europe. Two became four, as his travels took him to Britain and across the Continent to Greece and Istanbul.

During his travels Everett met many of the era’s most prominent figures, including Goethe and Byron. He pursued advanced studies at the University of Göttingen, where in 1817 he became – or so he thought, and historians seem to concur – the first American to receive a PhD. Throughout this period he kept extensive diaries which, though never published, informed the Mount Vernon Papers, a series Everett wrote in 1858 for the New York Ledger in an effort to raise funds for the purchase of George Washington’s Mount Vernon Estate.

After finishing his studies at Göttingen, Everett spent the winter of 1817-18 in Paris, where he dedicated himself to learning spoken modern Greek, a pursuit he had begun in Germany, under the tutelage of a fellow student, a Greek from Chios. It was at this point that he started learning to actually speak and write the modern language. Thanks to that unknown young man, in Paris Everett first came into contact with Adamantios Koraïs (1748-1833), the philologist and philosopher of Greek independence. Koraïs, who was born in Smyrna, had lived as an expatriate in Paris since the late 1780s and maintained a celebrated correspondence with Thomas Jefferson. Everett wrote about Koraïs in one of his Mount Vernon Papers, where he refers to the ‘frequent interviews’ that he, a young man of 24, enjoyed with the Greek intellectual – by then ‘seventy years of age and of rather infirm health, but of full possession of his faculties’.

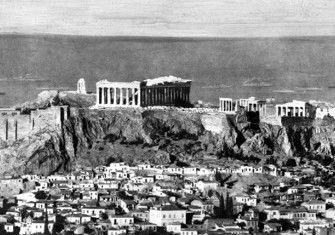

It was not until 1819 that Everett finally undertook his journey to Greece, bearing letters from Koraïs to various contacts. Everett set foot where few Americans had gone before him. Travel to Greece and the Ottoman Empire had become more common for Grand Tourists at the end of the 18th century, when the Napoleonic Wars closed off the more familiar corners of the European continent to leisurely travel. Everett’s own accounts of his travels in Greece and the Ottoman Empire differ little from the other narratives composed by the small group of travellers, who sought out antiquities in that era. Like many, Everett read his experiences largely through the lens of Byron’s poetry and Chateaubriand’s 1811 L’Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem. What is remarkable about Everett’s journey is the action it inspired when he returned home.

In 1821, two years after Everett came back to Boston to take up his duties at Harvard, war in Greece at last broke out. Greece had been under Ottoman Rule since the mid-15th century, but the first major uprising had not taken place until the Russian-aided Orlov Revolt of 1770. Now, inspired by the nationalistic principles of the Enlightenment and successful revolutions in America, France and Haiti, Greek revolutionaries in Greece and Europe gathered strength and resources for a more concerted and widespread attempt at revolt. Its origins lay primarily in the Filiki Etaireia, a transnational patriotic brotherhood focused on Greek independence and founded in Odessa in 1814 – the year before Everett departed for Europe. By 25 March 1821, the day now remembered as Greek Independence Day, orchestrated revolts had broken out in the Peloponnese and a number of islands.

In May of 1821, with the war just months old, the Greek revolutionary leader Petrobey Mavromichalis issued an appeal before an assembly of the Messenian Senate, the governing body of the Greek revolutionary leaders convened in the Peloponnesian town of Kalamata, for US aid to the Greek cause. In making the appeal for ‘citizens of America’ to help the Greeks ‘purge Greece from the barbarians’, Mavromichalis cannily invoked the affinity of American and ancient Greek liberty: ‘it is in your land that Liberty has fixed her abode, and by you that she is prized as by our fathers’. Soon a small embassy sent by the revolutionaries arrived in Paris, where its members consulted with Koraïs about spreading word of the revolution.

Koraïs immediately thought of Everett, who by then was editor of America’s foremost literary periodical, the North American Review. In July 1821 Koraïs sent him a copy of the proclamation of independence issued by the revolutionaries. Koraïs’ respectful yet affectionate cover letter begged Everett, as ‘wise Hellenist and Philhellenist’, to see that the proclamation be published in America. Everett did not fail his friend and over the next years worked vigorously on behalf of the Greek cause.

Everett engaged in a vigorous correspondence with his old friend Daniel Webster, then a US congressman. He encouraged Webster to advocate for American intervention in the Greek war and was a driving force behind Webster’s political activity on that front. On 2 December 1823 President James Monroe articulated the Monroe Doctrine of American non-intervention in European affairs. Yet, less than a week later, on 8 December, an undeterred Webster motioned in Congress for formal recognition of Greek independence and support of the war effort. Soon after that, on 19 December, Everett himself gave an impassioned speech at a meeting of the Boston Committee for the Relief of the Greeks, of which he was the founder.

Ten days later, on 19 January 1823, Webster delivered his own Greek speech from the floor of the House of Representatives. He began by invoking the legacy of Greek antiquity: ‘This free form of government, this popular assembly, held, for the common good, where have we contemplated its earliest models?’ Yet he insisted that he had not made his motion ‘in the vain hope of discharging any thing of this accumulated debt of centuries … What I have to say of Greece … concerns the modern, not the ancient; the living and not the dead’. Everett had made the arduous winter journey from Boston to Washington and was present to hear Webster speak.

Despite the US policy of non-intervention, many individual Americans worked to send resources – money, arms and medicine – to Greece, and a handful of American ‘Philhellenes’ even travelled there to participate in the war. Despite American enthusiasm for the revolution, it was not until 1837, five years after the war ended with a peace brokered by the Great Powers, that the US formally recognised Greece as an independent country and established consular relations.

In the intervening years, Everett’s own oratorical career had taken off dramatically. Throughout the 1820s he had built his reputation with a series of patriotic speeches given to commemorate landmark events in American history – the Pilgrim landing at Plymouth; the Battles of Lexington and Concord; the signing of the Declaration of Independence; and the deaths – on 4 July 1826, the 50th anniversary of American independence – of Founding Fathers John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. Yet Everett never forgot the Greek cause. He maintained correspondence with American Philhellenes – among them Samuel Gridley Howe, an abolitionist, future first director of the Perkins School for the Blind and the most famous American to travel to Greece and join the fight on the ground. He also kept in contact, in French, with Greek revolutionaries, including the cosmopolitan statesman Alexandros Mavrocordatos and even Theodoros Kolokotronis, general and leader of the Greek War of Independence.

Everett’s dedication to Greek independence was ultimately rooted in a number of chapters in his own biography. Ever since his late teens, he had shown an interest in and advocated on behalf of modern Greek literature and Greek independence. He had studied Modern Greek, visited Greece and struck up an acquaintance with some of the architects and philosophers of Greek nationhood. Yet one cannot help but surmise that, in the Greek revolution, Everett discerned an opportunity to redeem the one disappointment of his own ardent patriotism, at having been born a few decades too late to participate in his own country’s War of Independence, too late to see his own name engraved on the roster of its Founding Fathers.

Today Everett’s life is known, in various quarters, for various highlights, yet rarely are all its pieces assembled. His most recent biography, Mark Mason’s Apostle of Union, appeared in 2016. It is, however, a political biography and begins with Everett’s first term in the House of Representatives. Mason makes little of Everett’s career as the ‘wise Hellenist and Philhellenist’. Classicists, on the other hand, know Everett from the opposite direction: as the first Eliot professor of Greek at Harvard, the first American to take a PhD, a collector of Greek manuscripts abroad and an ardent educational reformer. Everett worked tirelessly and thanklessly to bring German models of education to the United States – itself a revolutionary move, in an era when Greek lessons consisted of rote memorisation and grammatical drilling.

The story is different in Greece, where Everett is best known as an American who dedicated himself to the cause of Greek freedom. In Athens an anaglyph bust of him appears on the American Legion monument to American Philhellenes. And while Everett’s travel diaries have never been published in English, a portion from the year 1819 (when Everett visited Greece) was published in 2010 – in Greek. Everett’s informed activism on behalf of Greek independence is perhaps the first great example of American ‘engaged scholarship’, fitting for the scholar who was the first in his country to earn a PhD.

Johanna Hanink is the author of The Classical Debt: Greek Antiquity in an Era of Austerity (Harvard, 2017). This essay is dedicated to the memory of Albert Henrichs (1942-2017), Harvard University’s latest Eliot Professor of Greek Literature as well as a great expert on, and enthusiast of, Edward Everett.