The Electric City

London’s West End came to life in the late 19th century, its glamorous attractions illuminated by innovations in electric light. The night, once associated with peril and danger, was reclaimed for leisure.

Piccadilly Circus, author's collection.

The first illuminated sign in Piccadilly Circus was erected in 1908. The attractions of Perrier and Bovril were lit up for Londoners. Soon after, theatres such as the nearby London Pavilion music hall adopted electric displays to alert viewers to the latest shows. The bustle and traffic around the statue of Eros established Piccadilly Circus as one of the most recognisable spaces in London, but also proclaimed that the West End was one of the world’s great pleasure districts, comparable to Times Square in New York and the Champs Elysée in Paris, both known increasingly for their bold lighting, emblems of cities that never slept.

Pleasure districts are vital parts of the urban experience. They were (and are) spaces of recreation, entertainment and spectacular retail, offering novelty and luxury. Moreover, they have represented a longer historical process across the globe where the night, once associated with peril and danger, was reclaimed for leisure. Major cities in the 19th century developed distinctive clusters of theatres, department stores, grand hotels, upmarket restaurants, smart fashions, dance halls, galleries and concert venues. These pleasure districts were not just products of their period’s turbo-capitalism, they actively constructed modern ideas of pleasure, fashion and taste.

By 1914 there were 43 theatres and music venues in the West End of London as well as 35 cinemas. Even ‘East Enders’ began to speak of the joy of going ‘up west’. Pleasure districts were also notorious as sites for prostitution. When shopping with his wife on Piccadilly Circus, Oscar Wilde was shocked at the rent boys (conspicuous by their use of make up) offering sexual services in broad daylight.

The West End of London first became an embryonic pleasure district during the late 18th century. The Theatre Royal Drury Lane was already viewed by many as, in effect, a National Theatre. In 1764 an establishment run by a Mrs Martin off St James’s Square seems to have been Britain’s first hotel. In 1798, Rules, London’s first restaurant, was founded on Maiden Lane off Covent Garden (and remains there today).

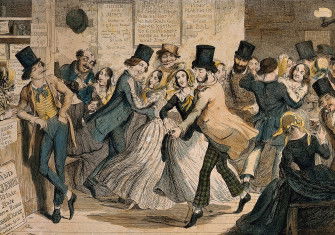

But it was the mid-19th century that really established the modern West End. The taverns around the Strand in the 1830s and 1840s helped develop the song and supper evenings that became Victorian music hall. The bazaars and arcades of the West End evolved into a distinctive form of retail: the department store. Shows at the theatres on Leicester Square, such as the Alhambra, became known for their exuberant spectacle. The West End was therefore a laboratory of mass entertainment that has shaped notions of luxury and fun ever since. It also confirmed London's status as a capital city.

One spot in the West End became a space of innovation that remains conspicuous today: the Savoy complex on the Strand. This was the brainchild of the agent and impresario Richard D'Oyly Carte (1844-1901). He is now best known for seeing the potential of Gilbert and Sullivan, whose light operas shaped middlebrow musical entertainment for generations: HMS Pinafore, The Pirates of Penzance, The Mikado and more. D'Oyly Carte was able to leverage the success of Gilbert and Sullivan by building a new theatre to house their comic glory. The Savoy Theatre, when it opened in 1881, was the first building in the world lit throughout by electricity. At the first performance the impresario had to address the audience to reassure them that electricity was completely safe. Another first was the theatre queue, which was introduced at the Savoy to reduce the disorderly scramble for tickets at the box office.

The success of the Savoy Operas was such that D'Oyly Carte was able to build a spectacular hotel around his theatre. He wanted to compete with the grand hotels that had emerged in Paris and other major cities: establishments that could offer the best of everything to aristocrats and the international plutocracy. One major innovation that he insisted upon was that each bedroom was to have a bathroom. This was such a contrast to previous hotel practice that, when told the Savoy would have 70 bathrooms, the builder asked if the guests were amphibious. To manage the Savoy Hotel, he chose César Ritz, who had established a reputation in Europe for running luxurious restaurants. The best staff were poached from continental hotels, including the celebrity chef Auguste Escoffier. Ritz (who would later give his name to the grand hotel on Piccadilly) was such a perfectionist that he spent hours experimenting with soft lighting in the restaurant so that ladies would always look their best.

D'Oyly Carte and Ritz were typical of the entrepreneurs who made the West End. One characteristic of the pleasure district was that it created a cultural synergy with theatres and shops feeding off one another. The pre-theatre dinner became a staple of West End restaurants, allowing guests to finish in time for a show. When Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado premiered at the Savoy in 1885, the costume designer deployed Japanese silks purchased at Liberty’s on Regent Street.

The West End was itself a form of spectacle. Over at the Gaiety (the home of burlesque) on the Strand, the manager John Hollingshead promoted the establishment by bringing over an electric searchlight from Paris. Installed on the roof, six arc lights beamed messages up into the night sky in 1878 to promote the theatre (a practice new to London). Well before the illuminated signs of Piccadilly Circus, the West End was associated with illumination, the bold lighting acting as a siren drawing audiences in to the latest show while screaming its modernity.

Pleasure districts introduced a new kind of urban living. The Grand Hotels of the West End and some of its upscale restaurants were at first affordable only by the wealthy, but improvements in transportation soon allowed people further down the social scale to access it. The district allowed for the creation of the ‘night out’, where men and women could dine at dine at restaurants like Gatti’s on the Strand and then take in a show at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane (famous in the late 19th century for offering spectacular imperialist melodramas that reaffirmed London’s status as the heart of Empire). West End theatres helped construct modern celebrity culture and traded on the star system. William Terriss, for example, became a matinee idol with his dashing good looks, pulling in the crowds to the Adelphi for melodramas such as William Gillette’s Secret Service. He was murdered in 1897 at the stage door of the Adelphi by a fellow actor and his ghost is thought to still haunt the theatre. Big stars were magnets, attracting fans who flocked to the West End hoping to catch a glimpse of glamour. Popular magazines such as the Play Pictorial enhanced the fascination with West End shows, the clothing worn by actresses shaping the development of women’s fashions.

The appeal of pleasure districts like the West End is to be found in how they differ from anonymous suburbs or from places of work. The bright lights stood for innovation, drawing people in to the centre of town, a glamorous and spectacular rebuke to the Victorian love of the domestic.

Rohan McWilliam is the author of London's West End: Creating the Pleasure District, 1800-1914 (Oxford University Press, 2020).