Best of Enemies: Europeans in the Ottoman Elite

European Christians who converted to Islam in the Ottoman Empire were vilified as traitors who had defected to the arch-enemy. But there is a big difference between official propaganda and the lived experiences of these ‘renegades’.

Topkapi Palace, Istanbul. INTERFOTO / Alamy Stock Photo

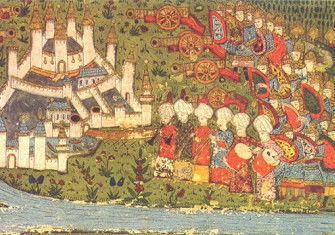

In 1598 a number of Ottoman ships approached Sicily. The sight of the vessels must have caused alarm since raids on the Italian coast were commonplace in the 16th and 17th centuries. Only four years earlier, a fleet had sacked the Calabrian port town of Reggio, just across the strait from Messina. Were the ‘Turks’ back for more booty, more men, women and children to carry off into slavery? Aboard the flagship was the admiral of the Ottoman navy or kapudan paşa, Ciğalazade Yusuf Sinan Pasha. This time, he had other intentions. Pledging his own son as well as two of his galleys as sureties, Ciğalazade requested permission from the viceroy of Sicily to meet with a number of the island’s inhabitants. The admiral had originally been born in Sicily and those he longed to see were his mother and his relatives.

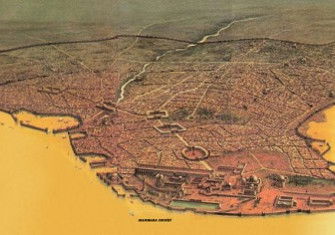

Generally known in European literature by his Christian name, Scipione Cicala, Ciğalazade was born in 1544, the son of a Genoese nobleman and corsair. In 1561 he and his father were captured at sea by Barbary corsairs and brought to the Ottoman capital, where Scipione converted to Islam, took the name Yusuf Sinan and entered the school at Topkapı Palace. Such training predestined him for high office within the sultan’s service. In addition to holding several provincial governorships in eastern Anatolia, Iraq and Syria, Ciğalazade served as kapudan paşa twice (1591-5 and 1598-1604). In 1596, he was even appointed grand vizier, becoming the second most powerful man in the Ottoman Empire, albeit for little more than a month.

Cicala’s legacy endures. In Istanbul, the neighbourhood of Cağaloğlu (the Turkish rendition of the Persian Ciğalazade, literally ‘son of Cicala’) takes its name from the location of his former palace. In Europe, too, his memory remains alive in popular culture. In 1832 Johann Philipp Rehfues wrote a massive four-volume novel based on the admiral’s life as an homage to Sir Walter Scott. As late as 1984 the man was commemorated in the song Sinàn Capudàn Pascià by the Italian singer-songwriter Fabrizio de Andrè. The piece is noteworthy because the lyrics are in the Genoese dialect in reference to Ciğalazade’s paternal ancestry, even though there is no indicator that he ever spent a significant amount of time in the north Italian city.

Ciğalazade was only one of a large number of European Christians who embraced Islam and served the Ottoman sultan in the early modern period, but his story is in many ways typical of the best known among their number. Parallels are most obvious in the case of two of his predecessors as admirals of the Ottoman fleet: Kılıç Ali and Uluç Hasan Pashas. Both men were born in Italy – Ali in Calabria, Hasan in Venice – and had entered the Ottoman Empire as captives of the Barbary corsairs. Rising through the ranks, first of the corsairs and then the Ottoman imperial navy, both attained positions of power, influence and wealth. Kılıç Ali Pasha is best known today for leading the Ottoman vessels under his command away from Christian adversaries during the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, when he realised that the engagement would end in defeat for the Ottomans. In recognition of his prudence as well as his nautical experience, Ali was appointed kapudan paşa

In Istanbul as well as Tunis and Tripoli, their Christian birth placed these men in good company. By the late 16th century it had in fact become a commonplace in European accounts of the Ottoman Empire to claim, as the Patriarch of Venice Matteo Zane did in 1594, that all the most important affairs of the Empire – its military, its government and all its riches – had been entrusted to such renegades (literally deniers, meaning apostates), as Christian Europeans dismissively called these individuals. Recruitment through the devşirme – the infamous boy levy – ensured that the majority of those in the upper echelons of the sultan’s service were converts to Islam. Out of 26 grand viziers who served the Ottoman sultans in the 16th century, a staggering 22 had converted to Islam from Christianity; only four were the sons of Muslim fathers (who, in turn, had probably embraced Islam later in life). The most famous of these convert pashas were Süleyman the Magnificent’s first ministers İbrahim (in office 1523-36), Rüstem (1544-53) and Sokollu Mehmed Pashas (1565-79).

It comes as no surprise, therefore, that renegades inspired hatred. In the eyes of many of their former compatriots, they were apostates and traitors, who had abandoned the true religion for the cause of what Christian propaganda all over Europe decried as Christianity’s arch-enemy. Zane, for example, echoing sentiments expressed by his predecessors, denounced these converts as ‘the most arrogant and wicked men one can imagine’. This sentiment likewise appears in travel and captivity narratives, where converts from Christian Europe, much more so than those hailing from the Christian communities of Ottoman territory in Anatolia and the Balkans, attracted particular scorn. The Bohemian nobleman Wratislaw of Mitrowitz, for example, characterised Ciğalazade as ‘a great enemy of the Christians’. Such conclusions seemed to derive justification from events like the sack of Reggio, which had occurred under the Italian-born admiral’s immediate command.

*

Why, then, did Ciğalazade want to see his family in 1598? According to the English ambassador Henry Lello, rumour had it that the admiral was either contemplating returning to Christianity, or intended to take his relatives to the Ottoman Empire. Pope Clement VIII had high hopes that the admiral could be convinced to return to his ‘spiritual mother’, the Catholic Church, and rise against the sultan. Although the hope that such a rebellion would destroy the Ottoman Empire and create a new Byzantium – this time ruled by Catholic monarchs – was entirely illusory, Clement took this prospect so seriously that he enlisted the financial and military support of the king of Spain and the Holy Roman Emperor. The idea seems to have been that Ciğalazade and his supporters – their number was grossly overestimated in Rome – would first take control of Istanbul and then gradually conquer the rest of the Ottoman Empire. Rudolf II was to send troops by land to support the rebellion, while Philip II would send a galley fleet. Philip may, in fact, have readied a fleet of 50 galleys for such an operation in 1603.

The plot was never implemented, though, and Ciğalazade may not even have known about it in the first place. It seems that the plan was suggested by Ciğalazade’s younger brother Carlo, who had remained in Sicily, and his two Jesuit cousins as a stratagem in the family’s pursuit for social advancement in Europe. In connection with the plot, Carlo was elevated to the rank of a count in the Holy Roman Empire and admitted to the Order of Saint James of the Sword, to which his corsairing father had already belonged.

The second possibility mentioned by Lello was no less likely. Indeed, the idea of bringing Ciğalazade’s mother to the Ottoman Empire surfaced time and again for a special reason. As diplomatic reports attest, contemporaries were well aware that she had been born an Ottoman Muslim. Her husband had taken her captive during an attack on an Ottoman port city and she converted to Christianity. Islamic law demanded that she be returned to Muslim lands to be offered the chance to reassert Islam or otherwise accept punishment for apostasy.

The demand to settle her in the sultan’s domain, in fact, features in a command issued by Sultan Mehmed III (r.1595-1603) to Carlo in November 1598, that is, after Ciğalazade’s return to Istanbul. Even Carlo’s own continued adherence to Christianity was a matter of debate in Ottoman elite circles. Mehmed III’s order, solicited by his brother, the admiral, appointed the younger Cicala brother ruler of the vassal duchy of Naxos. This island principality had been founded by a Venetian patrician in the 13th century but had since fallen into Ottoman hands.

Although Carlo never actually took the post because he unsuccessfully sought to renegotiate the conditions of his appointment, the mere fact of the offer calls into question the still popular notion of a clash of civilisations. Carlo was, after all, a subject of the Spanish crown, the Ottomans’ chief rival in the Mediterranean in the 16th century. He therefore was an unlikely choice for this strategically important region. That the younger Cicala seriously contemplated accepting the offer calls into question the effectiveness of the anti-Ottoman rhetoric energetically disseminated across Europe.

The renegade brother was, in fact, far from an embarrassment for Carlo. Instead, the admiral was a valuable asset in the quest for social advancement as an ally and patron as well as a source of prestige. Venetian sources are unequivocal in reporting that the original idea of seeking appointment by the Ottomans had been Carlo’s. Seeking to realise his trans-imperial aspirations, he travelled to Istanbul as early as 1593 but had been forced to return empty-handed because his brother, as Zane remarked, would not support him. Perhaps the two men had hatched the plan of a return visit on this occasion.

While such a visit was denied in 1594, prompting the attack on Reggio, four years later the Sicilian viceroy granted Ciğalzade’s request. His mother and other relatives were rowed out to sea to reunite with the Ottoman admiral aboard his ship off the coast of Sicily. Although certainly a special occasion, it was only one of several encounters between Scipione Cicala and his family following his conversion.

Other converts, too, maintained such contacts, providing money, support and protection to their relatives abroad and sometimes even engaged in charitable works in their former homes. In doing so, Christian-European renegades behaved no differently from fellow members of the Ottoman elite such as Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, who funded public works in their birthplaces and provided patronage, obtaining lucrative offices in the sultan’s service for their Muslim relatives and appointments in the Orthodox Church for their Christian kin. Religious boundaries were more permeable in practice than the rhetorics of crusade and jihad would suggest.

*

While most of our knowledge about such permeable religious boundaries relates to Italian-born renegades, it was a wider phenomenon. In 1572, for example, the theologian Adam Neuser from Heidelberg sought refuge in the Ottoman Empire. He had come into conflict with local authorities over his views about Christ and provocatively positive attitudes towards the sultan, both of which had earned him the death sentence. After crossing into Ottoman territory, he embraced Islam, allegedly performing circumcision on himself. A few years later, Neuser’s son tried to reach the Ottoman capital, only to be arrested by the authorities in Vienna.

Both Neuser and some of his associates in Istanbul continued to correspond with friends and relatives in Christian Europe as well as compatriots in the Ottoman capital. The activities of European diplomats, in particular, relied heavily on these characters within the Ottoman elite. Such men – we only rarely catch a glimpse of convert women – worked as translators, intermediaries in everyday diplomacy, guides and information brokers, even spies. Neuser’s cooperation with the Holy Roman Emperor’s ambassador in Istanbul, for instance, secured his son a place at the University of Vienna as well as a scholarship from the emperor himself.

The rhetoric of the treacherous and unreliable renegade notwithstanding, both sides often had a vested interest in ignoring the antagonistic rhetoric which proclaimed the Christian-turned-Muslim socially dead. Given their prominence in terms of numbers as well as status in the Ottoman Empire, pragmatic necessities required a more flexible approach. Countless Christian European-born Muslims deliberately sought out the company of fellow countrymen and women who evidently were unwilling to repudiate them. These converts did not become people without a history. While at times potentially threatening – for instance when a well-placed spy divulged sensitive information – their backgrounds and attachments were a resource of sufficient value to the Ottomans to justify the risk.

Converts were important to the Ottomans in this period precisely because they were outsiders, often even foreigners who spoke a variety of languages and brought with them experience of regions outside the sultan’s domains. It has often been claimed that alienness made such men ideal servants of the ruler because they lacked other attachments and were, thus, entirely dependent on him. This view is not only naïve but also misses the point that it was precisely the diversity and geographic spread of their attachments – kept very much alive within the technological limits of a premodern society – which, from an Ottoman point of view, constituted the value of their foreignness. For Christian Europeans – families, friends, rulers and their representatives – the new attachments which these converts formed within the Ottoman Empire represented an asset to be deployed at opportune moments.

Tobias P. Graf is the author of The Sultan’s Renegades: Christian-European Converts to Islam and the Making of the Ottoman Elite, 1575-1610 (Oxford University Press, 2017).