100 Years of Greater Lebanon

The disastrous explosion in Beirut has prompted calls for French intervention in Lebanon. But the history of France’s involvement in the region has been driven by the creation of proxy elites and the pursuit of its own interests.

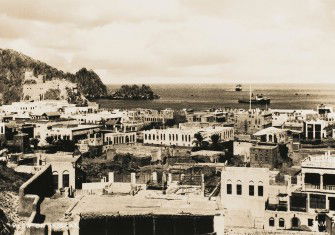

Proclamation of Greater Lebanon in Beirut, c.1920.

A petition circulated online in the aftermath of the catastrophic explosion in the port of Beirut on 4 August and French President Emmanuel Macron’s mobbed walkabout in the predominantly Christian, middle-class Gemmayzeh district of the city two days later. Attracting more than 60,000 signatures, the petition called for Lebanon to be placed ‘under French Mandate for the next ten years’, condemning ‘Lebanon’s officials’ and ‘failing system, corruption, terrorism and militia’. It asserted that a French Mandate would establish ‘a clean and durable governance’.

Subsequently picked up in the French right-wing press, the petition’s call for temporary French rule pursued a broader logic that ran through the majority of Western commentary on the explosion: Lebanon had to be fixed from the outside. Foreign aid and international support were deemed crucial to a recovery from the blast, but they should be aggressively conditional, imposing ‘reforms’ on Lebanon and supporting protestors’ demands for a wholesale removal of the country’s corrupt oligarchy. The crisis in Lebanon, this suggested, could only be resolved by external intervention – and France’s history of involvement in Lebanon appeared to make it a naturally prominent player in any such intervention.

As we pass the centenary of the formal creation of ‘Greater Lebanon’ in its current incarnation, formed by the French Army General Henri Gouraud on 1 September 1920, history can help us understand the deeper origins of the current crisis, the origins of modern Lebanon in foreign intervention and the reasons France occupies a role in its politics.

The French ‘Mandate’ to which the petition harked back was a form of colonial rule that lasted from the close of the First World War to the middle of the Second World War (Lebanon became formally independent in 1943). The ‘Mandate period’ saw the creation of both modern Lebanon and, crucially, Syria, from the territory of the collapsing Ottoman Empire.

The Mandate was held by France under the legal and diplomatic aegis of the League of Nations, an international institution that in the 1920s was dominated by Britain and France. In keeping with the racialised paternalism characteristic of the League’s approach to colonial empire, the Mandate system took its name from a term in private law describing the temporary guardianship of a child. As Article 22 of the League’s founding Covenant euphemistically described the arrangement: ‘tutelage … should be entrusted to advanced nations who by reason of their resources, their experience or their geographical position can best undertake this responsibility’.

The decisive French ‘experience’ that enabled them to acquire the role of ‘Mandatory’ was their victory in the First World War and the ensuing negotiations with the British – both an ally and a rival – to divide up Ottoman Palestine and Syria. French claims did not come out of the blue in 1918. Instead, they built on decades of intervention and influence in the Ottoman Empire where, from the mid-19th century, French capitalists had expanded their interests in tandem with burgeoning Catholic missionary and educational institutions. If Greater Lebanon was a French colonial creation in 1920, it had deep roots in the late Ottoman world.

In the second half of the 19th century, as European empires expanded frenetically and Beirut grew in population and economic importance, France increasingly positioned itself as a ‘protector’ of Arab Christian groups, intervening enthusiastically – notably in 1860 – to protect them during conflicts. Central to this were the Maronites, a community of Christians affiliated to the Catholic church, who lived predominantly in the highlands of Mount Lebanon. One important result of this trend was the British and French-mediated creation of an Ottoman autonomous administrative district (mutasarrifiyya) of Mount Lebanon during the 1860s. The Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifiyya was Maronite-dominated (though it also had a large Druze Muslim population) and was distinct from (though adjacent to and deeply connected with) the city of Beirut and the Ottoman province of the same name.

Ottoman Lebanon was therefore smaller geographically than the Greater Lebanon we know today, but the French consolidated their influence in the larger region by cultivating its Christian population and their political aspirations as a group within a territorial enclave. As the historian Ussama Makdisi has shown, a key aspect of this play of influence was the spread and institutionalisation of a novel idea: that the Ottoman population should be understood as a set of religiously defined ‘sects’.

This insidious concept, which seeded modern ‘sectarian’ politics in the region, was, however, just one tributary of a much larger, dynamic river of intellectual and political reformism in Ottoman Syria during the years around 1900. By the eve of the First World War, activists and thinkers across Ottoman Lebanon and Syria, reacting against or working with European influences and powerful Ottoman modernising efforts, had developed a diverse mixture of agendas, including Syrian or Lebanese nationalism, reformist-Ottomanism and Pan-Arabism. Some of these were premised on foreign support, many of them were liberal and democratic. Plans for Greater Lebanon were just one of these projects.

When French and British troops occupied a devastated, starving, inflation-ridden Beirut in 1918, the French authorities could look to an existing client group of mainly Christian ‘Lebanese’ (they also called themselves ‘Lebanonians’ in some instances, for instance in their large American diaspora). This group had existing connections to French interests and a maturing national programme, which existed in tension with plans for a Syrian nation-state. Importantly, though, that programme was defined as much by economic need as by historical or ideological reasoning. As the historian Carol Hakim has shown, the project of ‘Greater Lebanon’ rested on the precedent of the mutasarrifiyya and also on a claim to a continuous Lebanese past dating back to the ancient Phoenicians – a helpfully cosmopolitan and entrepreneurial crew of precursors for a commercially dynamic region. But the war and its accompanying famine had brutally reinforced the Maronites’ sense that Lebanon was dependent on food imports from Syria and vulnerable to incorporation into a larger Syrian state, one potentially careless of Christian prerogatives. The French stoked these worries, for example, by mistranslating the first article of the progressive, short-lived Syrian constitution of 1920 as ‘Islam is the religion of the state’ rather than the reality: ‘Islam is the religion of the King’. The solution to this problem was Greater Lebanon.

Instead of risking the return of famine and economic insecurity through the isolation of a small Lebanon, or else risking political incorporation into Muslim-Arab Syria, Maronites and French officials hoped that a French-sponsored Greater Lebanon would overcome the crisis. Incorporating the largely Sunni Muslim lands of the Bekaa Valley to the east of Mount Lebanon and adding further new territory along the coast to the north and in the Shia majority south, outside of the mutasarrifiyya’s old borders, Greater Lebanon had a colonial flavour. This was because it was enabled by French military power and because of the vanguard role it gave to the Maronite Christian elite in Beirut, who freely compared themselves to the Piedmontese of Italy’s unification and who often looked down on the largely Muslim rural and small-town classes on the periphery of the new state. Last month’s petition to Macron is nostalgic for such an arrangement.

France faced immediate and massive opposition to its rule in Syria, where it subdivided the country and aimed to create a system of ‘minority’ groups through whom to violently divide and rule. But even in Greater Lebanon, France, cash-strapped by the war, failed to commit adequate resources to deliver on the dreams of 1920. As the historian Elizabeth F. Thompson has shown, in the following decade, as the Lebanese Republic was established in 1926 and a parliament elected in 1929, the French increasingly resorted to authoritarian proxy-rule. French High-Commissioners, hamstrung by austerity in Paris, disproportionately favoured their Christian clients and, more generally, empowered wealthy, patriarchal elites, endorsing their skilled appropriation of sectarian political logic to divide access to power and resources. The result, long before the Lebanese civil war of the 1970s and 80s, was to limit the political potential of genuinely national ideas of citizenship. It is these ideas which the protesters in Lebanon are currently trying to resurrect, encapsulated by the call to expel the elite: ‘all of them means all of them’.

They face a steep challenge. By the time Sunni Muslim and Christian elites from Beirut’s oligarchic ruling class came together in 1943 to forge a National Pact, Lebanon’s political-economic course was in some respects set. French financial, commercial and cultural interests would continue to be interlaced with the Maronite community in particular. More generally, access to political and economic power was organised around sectarian identities, even during the laissez-faire boom years of 1940-75, when a cloud of money partially obscured the political realities. Even the later rise of Shia political power, through the Iranian-backed Hezbollah, would create a new sectarian player rather than destabilising the underlying system. The arrival of further external players, from Syria, the US, Israel and Iran built on the French template.

Emmanuel Macron was back in Beirut on 1 September 2020 to mark the centenary of Gouraud’s creation of Greater Lebanon. Keen to get away from domestic controversies and play to the residual Catholic and Gaullist sentiments of the French electorate, he alluded selectively to France’s long history of involvement in the region, much as French officials did a century ago. His calls for unity made much of France’s humanitarian commitment to the Lebanese people and he again insisted (while supporting a new Lebanese prime minister who used to advise a former Lebanese prime minister) that the Lebanese elite must attend to popular demands for ‘reform’ by revising the existing political structure.

Any such changes will need to overcome deeply entrenched structures dating back to the French Mandate period itself. If, as the Lebanese Druze sectarian chief Walid Jumblatt has claimed, the present moment in Lebanon is most analogous to ‘the end of World War One, a time of looming famine and dreadful Spanish Flu [when] we were buying grain from Syria and locusts were plaguing the land’, then it is to be hoped that a century later, France will not, as it did then, sabotage democratic hopes in favour of proxy elites and its own interests.

Simon Jackson is Lecturer in Modern Middle Eastern History at the University of Birmingham.