Who Lost Czechoslovakia to Communism?

After its liberation in 1945, Czechoslovakia soon fell behind Stalin’s ‘Iron Curtain’. That it would do so was not a formality: the US could have brought the country into the Western Bloc – had it been so inclined.

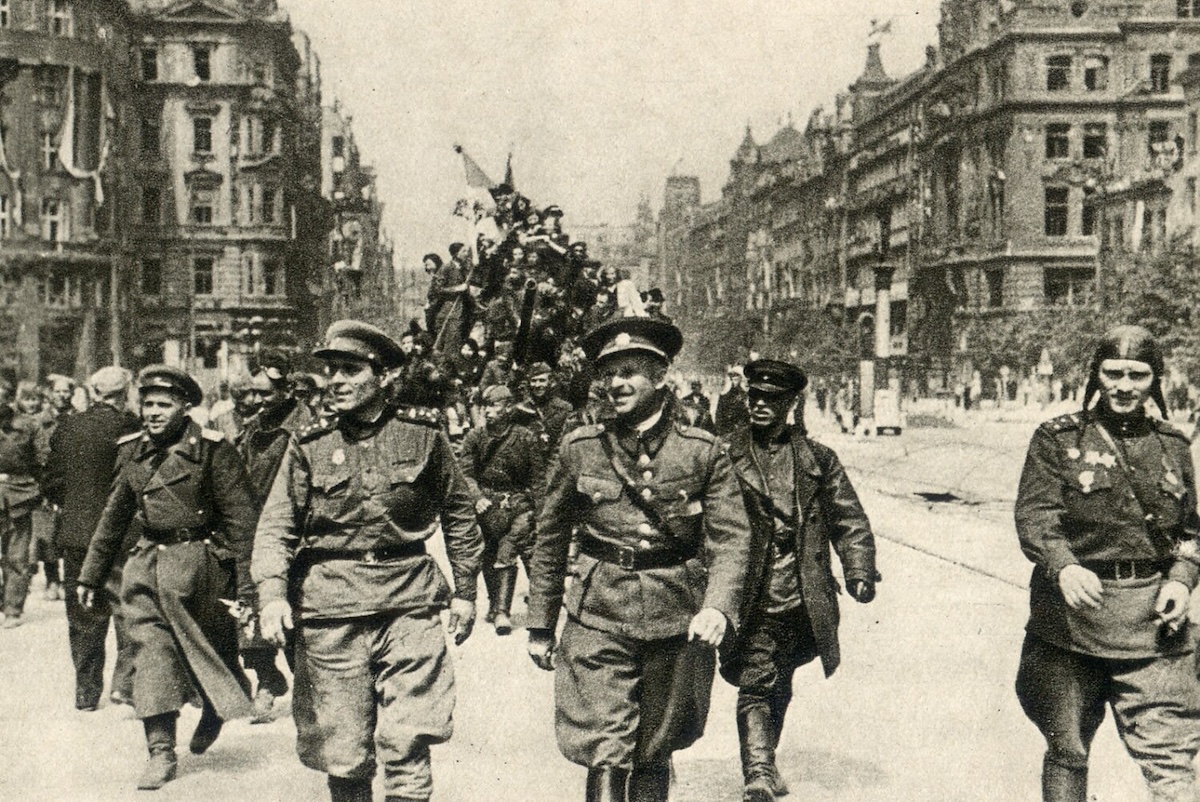

The Red Army arrives in Prague, 9 May 1945. Moravian Library in Brno. Public Domain.

It is often taken for granted that all European nations involved in the early Cold War, save Germany, fell naturally onto one side of the Iron Curtain or the other. Yet Czechoslovakia was not pre-ordained to become part of the Soviet sphere. There were multiple opportunities for the United States to influence its position on the political map of Europe.

Czechoslovakia emerged from the Second World War unaligned. Hitler and Stalin had not allocated it in the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. Stalin and Churchill had not included it in their secret 1944 ‘percentages’ deal, which designated spheres of influence in eastern and southern Europe. The victorious Allies had not discussed its orientation at Yalta or Potsdam. Both the Soviets and the Americans had liberated it. But whatever cards Washington had to play, diplomatically and militarily, it gave most of them up in 1945.

‘I believe that Russia wants to and will cooperate’ in Czechoslovakia, President Roosevelt told the Czech Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk, a democrat unaffiliated with any party, in February 1944. Red Army officials, however, made clear to their Czech counterparts that the country would be brought within the Soviet sphere. What capacity the US Army had to countervail was circumscribed by the fateful decision of Generals George Marshall and Dwight Eisenhower to stop its own advance 50 miles west of Prague.

The Red Army, which had been 150 miles further from the Czech capital than General George Patton just before the war’s end, marched into Prague on 9 May 1945. It was one of its easier victories, but also one that had great subsequent historical significance. ‘We could have liberated Prague’, lamented one bitter US embassy official. ‘After the war we spent a lot of time trying to convince the Czechs that they weren’t part of the Eastern Bloc. But no matter what we said, the Soviets came to Prague first.’ The Czech Communists used this to their advantage, proclaiming it as evidence that only the Russians cared about the Prague citizens being brutalised by the Nazis.

In the months that followed, the US War Department agitated for a complete withdrawal of US troops from Czechoslovakia. There was, Ambassador Robert Murphy said from Germany on 31 August, no ‘overriding political necessity’ for their presence in the country. In Prague, the US Ambassador to Czechoslovakia, Laurence Steinhardt, was appalled. He argued that withdrawal would make the Czechs ‘feel that they had been morally as well as physically abandoned by the Americans at the very time they were just beginning to show signs of courage in standing up to the Russians’. No one knew for certain how many Soviet troops were in the country at the time, but estimates spanned from 165,000 to more than twice that. President Truman decided to write to Stalin on 2 November proposing a simultaneous US and Soviet withdrawal by 1 December. Given that such a deal would tip the military balance of power in the country overwhelmingly to the Soviets, who would have hundreds of thousands of soldiers available near its borders to smother the country as necessary, Stalin agreed.

The Czech president Edvard Beneš – a democrat who came to despise the Communists –was thrilled to see foreign forces leave his country, assuming naively that it signalled Stalin’s commitment to its independence. Like Ambassador Steinhardt he thought, wrongly, that Klement Gottwald, the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and his fellow Communists were Czech patriots, who would be content to take a back seat in government rather than appeal to Stalin to remove the democrats.

At the time, the Communists were the largest party (though still a minority) in the National Front, a coalition of parties that headed the newly re-established Czech government, having won 38 per cent of the vote in the May 1946 elections. Stalin’s portrait was ubiquitous on Prague’s billboards. He was, whatever his imperfections, the closest thing the country had to a guarantee against another German invasion. When, at a Paris gathering of foreign ministers in August 1946, Jan Masaryk applauded Soviet deputy foreign minister Andrei Vyshinky’s condemnation of American loan offers as ‘economic enslavement’, US Secretary of State James Byrnes and the State Department turned against Masaryk and his government. President Beneš begged Steinhardt to understand that such regrettable public gestures were the price his country paid for being permitted a measure of domestic democracy. But with Masaryk’s behaviour being called out in the New York Times and the Communists, who railed against ‘dollar imperialism’, blocking any progress on compensating Americans for commercial property nationalised after the war, there was no way diplomatically to repair the breach.

When, the following summer, the Czechs, under orders from Stalin, reversed their initial embrace of the American offer of aid under the European Recovery Program – otherwise known as the Marshall Plan – the State Department wrote them off as a natural part of the Communist East. National Socialist Party Chairman Petr Zenkl was unapologetically pragmatic:

Our situation ... changed at the moment when the delegation ... was notified of the Soviet opinion toward the Marshall plan. The political perspective trumped the economic one. We remain a faithful ally, and accept both the advantages and disadvantages of this alliance.

Still, American diplomats in Prague appealed to their colleagues in Washington for understanding and patience. The US chargé John Bruins said that ‘80 per cent of Czech people favour western style democracy over Communism’ and pleaded for the State Department to help ‘consolidate this pro-western sentiment’. Steinhardt pointed out that ‘nearly 80 per cent of [the] country’s total foreign trade is still with [the] west’. Masaryk begged Washington to understand the ‘difficult situation caused by [Czechoslovakia’s] contiguity to the Soviet sphere’. His pleas fell on deaf ears. The division of Central European Affairs Chief James Riddleberger dismissed him as ‘weak or blind’.

The Czechs saw the State Department’s froideur as confirmation that America was still uninterested in them. ‘Those goddamn Americans’, Hubert Ripka, an advisor to President Beneš, said after agreeing a grain deal with Moscow in December 1947:

We asked for 200,000 or 300,000 tons of wheat. And these idiots started the usual blackmail ... At this point, Gottwald got in touch with Stalin, [who] immediately promised us the required wheat ... These idiots in Washington have driven us straight into the Stalinist camp ... The fact that not America but Russia has saved us from starvation will have a tremendous effect inside Czechoslovakia – even among the people whose sympathies are with the West rather than with Moscow.

For his part, Stalin still saw Czechoslovakia, which bordered both western Germany and Ukraine, as a weak link in the USSR’s defensive perimeter and was on the alert for signs of trouble. Masaryk provided them. ‘We know that the United States will not consider us its favourite sons after the rejection of the Marshall Plan’, he told the Czech paper Svobodne Slovo in October, ‘but we hope they will not completely forsake us.’

In December, the Soviet embassy in Prague cabled Moscow about troubling political developments: ‘Reactionary elements within the country, actively supported by representatives of the West, [believe] that the parties of the right will receive a majority at the forthcoming [May 1948] elections and that the communists will be thrown out of the government.’ Early in 1948, the National Socialists, the second largest party behind the Communists, expressed public regret about not having joined in the Marshall Plan. Elements in the Communist party now began agitating for Moscow to intervene. Stalin obliged.

The US State Department Sovietologist George Kennan had warned that this would happen in November of the previous year. ‘As long as communist political power was advancing in Europe, it was advantageous to the Russians to allow to the Czechs the outer appearances of freedom.’ It would permit the Czechs ‘to serve as bait for the nations further west’. But, he warned, once the ‘danger of the political movement proceeding in the other direction’ became apparent in Moscow, the Russians would no longer be able to ‘afford this luxury’. Czechoslovakia could stir liberal democratic forces elsewhere in the East. At that point, the Russians will ‘clamp down completely on Czechoslovakia’, even though they ‘will try to keep their hand well concealed and leave us no grounds for formal protest’.

Stalin’s opportunity came in February. On the 18th of that month, the four National Socialist ministers went to see Beneš to express their alarm over the Communist purging of the interior ministry. The hard-line Communist minister Václav Nosek was systematically replacing police commissioners with party loyalists, ignoring protests that his actions were illegal. The National Socialists, Populists and Slovak Democrats had decided, therefore, to resign their 12 ministerial posts, which amounted to half the cabinet. The ministers wanted Beneš to demand the resignation of the remaining cabinet members from the Communist leader Gottwald, paving the way for either a new government that would reverse the security measures or new elections.

Beneš agreed to back new elections. The Communists, he said, would never give way, as they could not win elections without controlling the police. As for the Soviets who were orchestrating the crisis, the brutal way they had blocked Marshall aid for the country still angered him: ‘They are provoking the whole world.’

Soviet deputy foreign minister Valerian Zorin arrived in Prague unannounced the following day, 19 February. Meeting with Gottwald, the Russian told him the time had come to ‘be firmer’ and to stop making ‘concessions to those on the right’. The premier had ‘to be ready for decisive action and for the possibility of breaching the formal stipulations of the constitution and the laws as they stand’.

On 20 February, with no sign that the Communists would abandon their takeover of the police, the 12 non-Communist ministers submitted their resignations. Gottwald rejoiced at the naiveté of their tactic. ‘I could not believe it would be so easy ... I prayed that this stupidity over the resignations would go on and that they would not change their minds’. The Communists organised Bolshevik-style ‘Committees of Action’ around the country and ordered police officials to pledge their ‘loyal[ty] to the Government of Klement Gottwald’ and to ‘obey all the orders of the Minister of the Interior.’ Workers were instructed to attend Communist rallies around the country. Those who refused were locked out or beaten.

Beneš saw the pressure around him growing by the hour. On 23 February, Minister of Defense General Ludvík Svoboda declared that the army ‘stands today, and will stand tomorrow, beside the USSR and its other allies, to guarantee the security of our dear Czechoslovak Republic’. The Communist-controlled interior ministry occupied the offices of the non-Communist press, instituting measures to prevent them ‘from disturbing public opinion by lies and provocations’.

Gottwald secured the cooperation of rebel members of the non-Communist parties, effectively making them part of his own party, and submitted a new cabinet list to the president. A communiqué declared the commitment of the new ‘Renovated National Front’ to ‘the purging of the political parties, whose responsible leaders have abandoned the principles of the National Front’, and to ‘tighten[ing] the alliance with the Soviet Union and the other Slav States’.

At noon on 25 February, to the shock of the now-former National Socialist ministers, the country learned from the radio that Beneš had accepted their resignations. He would himself resign a few months later, on 7 June. Gottwald would be elected president the following week. The Communist takeover was complete.

In the weeks immediately following the coup, there were mass purges and arrests. These were followed by a rewriting of the constitution and rigged parliamentary elections. Masaryk accepted reappointment as foreign minister, but his tenure was brief. In the early morning of 10 March, his body was found on the ground below his third-story office. A forensic investigation by the Prague police over half a century later concluded what many had believed at the time: that he had been pushed.

The coup raised the uncomfortable question in the State Department: ‘Who lost Czechoslovakia?’ Kennan had thought it inevitable that Moscow, which saw ‘only vassals and enemies’ near its borders, would do whatever was required to make it one of the former. But others disagreed. Hawkish scholar and State Department official Eugene Rostow later reflected that ‘failure to deter the Communist takeover of Czechoslovakia in 1948 was one of the most serious mistakes of our foreign policy since the war’. Allen Dulles, who would become director of the CIA five years later, blamed the calamity on incompetent American diplomacy and intelligence operations.

As the State Department’s John Hickerson put it, the ‘absence of any sign of friendly external force was undoubtedly a major factor in the limp Czech collapse’. But Secretary of State George Marshall was unmoved:

[A] seizure of power by the Communist Party in Czechoslovakia would not materially alter ... the situation which has existed in the last three years ... Czechoslovakia has faithfully followed the Soviet line ... and the establishment of a Communist regime would merely crystallize and confirm for the future previous Czech policy.

This thinking was both self-justifying and self-fulfilling. The State Department relied on it to make the case, to themselves and the rest of the world, that they could not help those who would not help themselves. He and Kennan had attached this fundamental principle to the Marshall Plan. The initiative had to come from Europeans themselves. America could not save nations that had lost the will to fight. This was a convenient rationalisation, as it meant that the State Department had not ‘lost Czechoslovakia’. The country, rather, never had what it took to be a Marshall Plan state. Marshall was only ‘concerned about the probable repercussions in Western European countries’.

This observation highlights perhaps the most important unrecognised truth about the Marshall Plan: that it succeeded in part by excluding Czechoslovakia and countries further east. Washington had been determined to use its economic leverage to counter Soviet conventional-force dominance in Europe, but such leverage was simply insufficient in the case of countries bordering the Soviet Union. They were, therefore, written off.

Benn Steil is director of international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations and author of The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War (Simon & Schuster and OUP, 2018).