Inflation – Who Wins?

Three historians discuss the historical phenomenon of inflation, focusing on the Roman Empire and the 16th century.

What causes inflation?

R.G.Opie, Fellow and Lecturer in Economics at New College, Oxford

Inflation is a sustained widespread rise in the general level of prices. This does not mean that every single price is rising, let alone at a steady pace. Some may remain steady for weeks or months at a time, and some may even fall for short periods but the general sustained path of the price level is upwards. If most or all prices are rising, that would include the price of labour - wages and salaries. If wages and salaries do rise broadly in line with prices, real standards of living are maintained. Although rising prices mean that any £ will pay for less and less, income receivers have more £s to spend. History reveals long periods of rising prices, but more recent British history – for which we have, in any case, better data – shows remarkable differences in different periods. The nineteenth century began with prices surging upwards, but the long-term trend until the outbreak of the First World War was downwards.

The twentieth century has two sharply contrasting periods. From the end of the post-war boom in 1921 prices fell steadily until the bottom of the Great Slump in 1933 – and have risen in each single year since then without a break. Of course, the rate of rise alters sometimes very fast, at 16 per cent between 1973 and 1974, and at 18 per cent between 1979 and 1980. At present the rate of inflation is low - only some 5 per cent a year. The rate of inflation has fallen although prices are still rising.

What causes inflation? If economists were to analyse rises and falls in a single price – say that of sugar or coffee – they would ask about changes in the demand for it and in the supply of it. If the demand rose but supply did not, eager buyers would bid against each other and the price would rise. Equally, if supply were to fall, the price would be bid up. Conversely if demand fell, or supply rose, disappointed would-be sellers would have to settle for lower prices.

This sort of analysis can be generalised to explain the broad course of all prices together – the general price level – until the 1930s, and perhaps even more recently. The dominant force in periods of fast rising prices was increased demand, usually generated by war, as in the Napoleonic period, or the First World War, whereas the long downtrend in the ‘Victorian’ price level can be largely explained by the large and continuing increase in supplies of manufactures from the growth of British industry, and in supplies of foodstuffs and raw materials from the world overseas.

Economists argue vehemently, however, about the role of changes in the money supply in the behaviour of prices. Are rises in the stock of money causal in themselves, or merely permissive? Obviously, if many people want to spend more but lack the finance to do so, they must borrow from those who have it - which will raise interest rates. Ultimately, that rise will place a lid on the rise in borrowing and in spending, and on prices. But if would-be spenders borrow instead from banks which create the additional finance, the rises in spending and prices could go further - and further. An elastic money supply is clearly permissive.

Could it be casual, in itself? When a large part of the money stock was gold and silver coins, large and sudden changes sometimes occurred - in the sixteenth century, and in the 1850s and 1890s, after large new discoveries of the metals. Therefore, say ‘monetarists’, the increased money stock caused the inflation.

The debate has been revived in recent times, and rages on. But things are now different. In particular, prices and especially price increases are now ‘managed’ across most of the economy, mainly in order to protect business profits against rises in costs. Far from prices being ‘pulled up’ anonymously by demand, prices are ‘pushed up’ by identifiable business managers in response to rising costs.

But what are ‘costs’? They are largely either wages and salaries, i.e. the great bulk of money incomes, or material costs, which do respond in relatively free markets to changes in demand. But wages and salaries are bargained, and are easier to raise than reduce. The main 'moral' force behind bargains is to sustain real incomes. Hence we generate a wage-cost-price-wage spiral, which works only upwards.

This ‘structuralist’ explanation sees inflation as the result of bargaining among three powerful groups in society managers who want profits, workers who want wages and salaries, and government which wants tax revenue from each. Structuralists see the stock of money as merely permissive, and changes in it in short periods as irrelevant.

There is no doubt that inflation is politically unpopular. It causes shifts in income distribution, making poorer those whose money incomes rise more slowly than prices. Inflation in one country faster than in its trading competitors loses that country shares in world markets, jobs and incomes, and generates trade deficits.

Governments have generally responded therefore to inflation by policies of deflation, i.e. by cutting total demand in the economy. Alas, output, jobs and incomes fall much sooner than the prices or even price increases. To avoid this dire outcome, governments have tried to restrain prices and costs by controls on them. Alas, these can work only by consent, which has generally been short-lived. Inflation seems here to stay.

The Roman Empire

Keith Hopkins, Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Brunel University

In the modern world, the rate of inflation is influenced by changes in the national and international economy. In the Roman world also, pressures to inflation were both internal and external. One significant cause of inflation was the cost of defending the empire against barbarian attacks. Another cause, and probably the most important, was the repeated inability of the central government in Rome to keep its expenditure within its income.

The Roman empire by the end of the first century AD covered the whole of the Mediterranean basin and beyond. It stretched from the north of Britain to the Red Sea, from the Atlantic coast in modern Morocco to the Black Sea. It had a population of about sixty million people, about one-fifth of the world's population at that time.

Most of the empire's population, probably four out of five, were peasants. They worked the land and were largely self-sufficient, producing most of what they ate. In addition, they produced a small surplus, which they paid as tax to the government in Rome. Many also paid rent to landlords.

The size of the Roman government's budget, its overall strength and its capacity to defend the empire were all limited by the size of the agricultural surplus, and by the central government's effectiveness in exacting its share. One problem was that the government had a very small staff (less than 200 élite administrators in all the provinces). It therefore depended upon landlords to collect taxes. This cut the cost of administration, but limited the central government's ability to tax landlords, and to increase revenues significantly.

The largest item in the budget was defence. A standing army of 300,000 soldiers was stationed in garrisons strung out along the frontiers, along Hadrian’s wall, for example, and along the rivers Rhine and Danube. The cities of Cologne, Mainz, Strasbourg, Vienna and Budapest all grew around legionary camps. Soldiers served twenty-five years in the legions and were well paid. At the end of their military Service, they received a bonus for long service and loyalty, equal to thirteen years’ pay, which was expensive for the government but worth waiting for.

In addition, emperors maintained a lavish Court in the city of Rome and placated the populace there with monthly rations of free wheat, regular chariot races and huge gladiatorial shows and wild-beast hunts in the Colosseum.

This cost money, and it repeatedly cost more than was raised in taxes. In times of emergency, when barbarians invaded and when civil war threatened, emperors felt obliged spend and could not afford to be limited by what lay saved the treasury. Nor was over-expenditure confined to serious emergencies. Self-indulgent emperors like Nero (AD 54-68) and Commodus (AD 180-192) just liked to spend lavishly on their Court, while others wanted to buy popularity at Rome or to stave off rebellion among truculent soldiers.

One after another, from Nero onwards, emperors resorted to two simple expedients. First, they gradually, and almost imperceptibly reduced the weight of new silver coins; they generally experimented with these reductions first in the provinces. Secondly, they reduced the proportion of silver in each silver coin. By combining these two tactics, they minted more silver coins than ever before, from newly mined silver and from old coins which were raked in by tax-collectors and melted down.

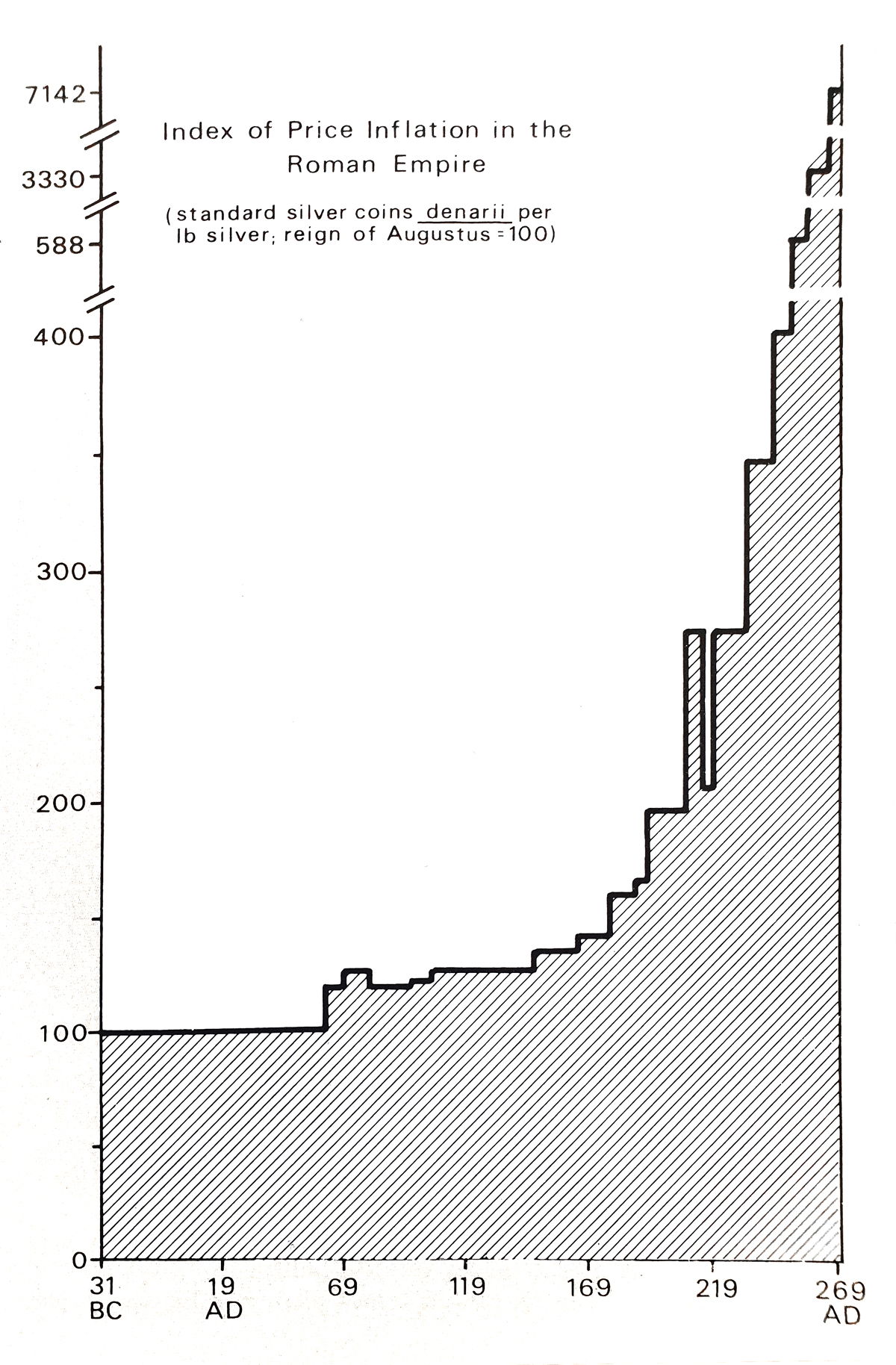

The volume of coins in circulation rose, and so did prices. At first, the process was gradual. But the pace of debasement grew faster, especially from the middle of the third century AD onwards. The chart shows the progressive debasement of silver coins and its probable impact on prices. Under the first emperor Augustus (31 BC-AD 14), silver coins were almost completely pure (98 per cent). In AD 110, they were still 89 per cent fine, but had been reduced to 14 per cent in weight. In AD 215, they were only 52 per cent silver, and in AD 270, coins had only 3 per cent of silver in them, just enough to give them a flashy look when new, which soon rubbed off.

Prices rose dramatically, because there were more coins chasing the same quantity or even fewer goods. For example, in AD 129, a slave girl cost 1,200 silver coins; two centuries later, a slave girl cost 42,000 silvered coins. The price of wheat per bushel rose from 1 denarius in AD 110, to 267 denarii in AD 301, to 36,000 in AD 338.

What were the consequences of rapid inflation? Peasants, because they lived off their own produce, were largely insulated from the deterioration of the cash economy. Those living off fixed cash incomes, principally soldiers and civil servants, were hit hardest. The soldiers hit back and tried to protect their standard of living by violence. They simply took the food which they needed from peasants by force. The period of inflation was also a period of increased disorder, of civil wars and foreign invasions. The Roman government was caught in a vicious spiral. Suppressing disorder increased government expenditure. More expenditure meant more debasement, which raised prices and provoked disorder. Many people preferred to barter and to exact goods and services in kind rather than trust the deteriorating coinage. Similar pressures nowadays help create the black economy.

In AD 301, the Emperor Diocletian tried to break this vicious circle by passing a law on Prices and Incomes. Throughout the huge empire, lists were posted of items, fixing maximum 1,800 charges for goods and wages, from chick peas to shirts, from carpentry to sea transport. But the policy failed, almost before the prices had been chiselled on stone. Market forces were too strong, and conditions too varied to be controlled by a single, centrally-dictated list of prices.

It should be emphasised that inflation was the symptom not the cause of Rome’s economic and political difficulties. And it was just as difficult to control then, as it is now.

The 16th Century

R.B. Outhwaite, Lecturer in History at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow and Tutor of Gonville and Caius College

In Europe around 1500 agriculture was the dominant economic activity: it employed most people and the commodities it supplied were vitally important - grains for bread and beer, grapes for wine, wool and hemp for textiles, hides for leather goods, oils and fats for lighting, cooking and lubricating. At some point around 1500 the prices of many of these commodities began to rise and they continued to do so for a century or more, the process ending variously between 1590 and 1650. In England, for example, the rise began around 1520 and ended around 1650: overall food prices rose six-fold, industrial prices perhaps three-fold. It was thus a modest inflation by today’s standards.

It came, however, in fits and starts, and whenever it speeded up it provoked discussion. In sixteenth-century England, for example, inflation was blamed on the farmers, who cultivated grass and sheep instead of corn, on wicked landlords who forced up rents, on middlemen and monopolists, on immigrants, and upon governments, who tampered with the currency, debasing the coins by reducing their weight or putting less silver and gold into them. Most European countries throw up similar catalogues of complaint.

In the 1550s scholars at Spain’s University of Salamanca came up with a new cause: they blamed inflation on the abundance of money deriving from ‘the discovery of the Indies, which flooded the country with gold and silver’, an argument that was a little later taken up by scholars in France and England.

Fifty years ago an American historian, Professor Earl J. Hamilton, argued that these bullion imports explained not only the Spanish price rise but the general European one also. Others pointed to the universality of currency debasements in this period, and for several generations people were inclined to argue that this European price rise was the result of these two forces combining to produce an increase in the quantity of money. Were they right?

Recently some historians have grown dissatisfied with monetary explanations of the sixteenth-century price rise. They have realised that prices in many countries began to rise before much New World treasure entered Spain, let alone left it, and that probable treasure-flows bear little relation to price movements, especially in Spain itself.

Also whilst there can be little doubt that sudden and severe currency manipulations could precipitate inflation (witness ancient Rome or the English experience between 1544 and 1551 when Henry VIII and his successors violently debased the coin), a lot of European debasements may be as much a product of inflation as a cause. Rising prices usually did put pressure on the money supply: governments attempted to expand it by debasement, a process which was internationally competitive, and sometimes overdone because it was fiscally profitable.

More attention has recently been paid to price disparities. Imports of treasure might reasonably be expected to increase the spending of the richer groups in society, thus expanding the demands for luxuries. Yet, in most countries, the price of luxuries rose much less than those of necessities. Basic foodstuffs everywhere bore the brunt.

At some point in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth century European populations began to expand again, recovering from that long era of contraction initiated by the Black Death of 1348. Growing populations produced rising demands for food, drink, cheap clothing, shelter, firewood, etc., all ultimately products of the land. Tudor farmers found it difficult to increase their output of these things: food prices, land values, industrial costs, all rose.

Such pressures are now seen as an important underlying cause of this inflation, though few would deny that it was stimulated at times by governments manipulating the currency, borrowing heavily, and fighting wars. But it is important to remember that one can find plenty of examples of governments doing all three of these things before 1500 or after 1650 without prices rising significantly.

Who won and who lost? Wage-earners almost everywhere found themselves at a disadvantage. Pensioners likewise found themselves amongst the losers. Many manufacturers found that rising raw material and labour costs created difficulties for them. Governments frequently found that inflation affected their expenditures more rapidly than their revenues.

Farmers on the other hand prospered, especially the larger ones. They rebuilt their houses and indulged in relative luxuries: silver sp0ons, pewter vessels instead of leather and wooden ones, feather beds, and warming pans the central heating of their day. Many landlords ultimately benefited from this farming prosperity, though not immediately. Merchants and manufacturers supplying goods to these prosperous elements did well.

Reading on inflation

Peter Donaldson, The Economicsofthe Real World (BBC Publications and Penguin Books, 1973); Michael Stewart, Keynes and After (Penguin Books,1970); J. Trevithick, Inflation (Penguin Books, 1977); J. Flemming, Inflation (Oxford University Press, 1976); A.H.M. Jones, The Roman Economy (Oxford University Press, 1974); F. Braudel & F. Spooner, Prices in Europe from 1450 to 1750' in E.E. Rich & C.H. Wilson (eds) The Cambridge Economic History of Europe, vol IV (Cambridge University Press, 1967); P.H. Ramsey (ed), The Price Revolution in Sixteenth-Century England (Methuen, 1971); C.E. Challis, The Tudor Coinage (Manchester University Press, 1971); R.B. Outhwaite, Inflation in Tudor England and Early Stuart England (2nd ed. Macmillan, 1982).

Today’s History

On Sunday 14 November 1982 at 4.30pm, the monthly television programme Today’s History began on Channel 4.

Today’s History reflected on television History Today’s approach to the past, showing the historical background to current affairs and examining historians’ perceptions on the past today. Each month a pull-out supplement provided readers with four pages of background to link with the subject of the television programme, in the form of chronologies, maps, charts, factual information, suggestions for reading, up-to-date surveys and historical insights.