Shadows at Noon by Joya Chatterji review

Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Twentieth Century by Joya Chatterji is a gently revisionist account of an enduring, if ever-tottering, democracy.

The Indian filmmaker Guru Dutt, known for his cloying tearjerkers about tormented poets and wilting royals, was often mistaken for a Bengali, Joya Chatterji tells us, on account of ‘his (hard-to-define) Calcutta ways’. But those ‘ways’ are not so elusive. Even a non-native like David Gilmour – of the peerage, not Pink Floyd – could pin it down. People often mistook his friend and fellow historian Ramachandra Guha for a Bengali, Gilmour observed, because ‘he talked in a way I had been told that bhadralok [Calcutta’s bourgeois] scholars always used to talk, rapidly and excitedly on a very wide range of subjects’.

Unlike Dutt and Guha, Chatterji is the real thing, a card-carrying member of the bhadralok, as she time and again reminds us in her new book. Shadows at Noon is a cheerful history of the subcontinent, by turns erudite, eclectic, analytical, gossipy and prolix – all instantly recognisable bhadralok qualities. In style and detail, it effortlessly surpasses Guha’s equally colossal India After Gandhi. The latter has gone through many reprints, selling hundreds of thousands of copies. By all accounts, though, it was a terribly conventional, even triumphalist, account of the wonder that is Indian democracy. Also scarcely forgivable was its unabashed bird’s-eye view. Hardly so much as a word was to be found on the lower orders in its pages.

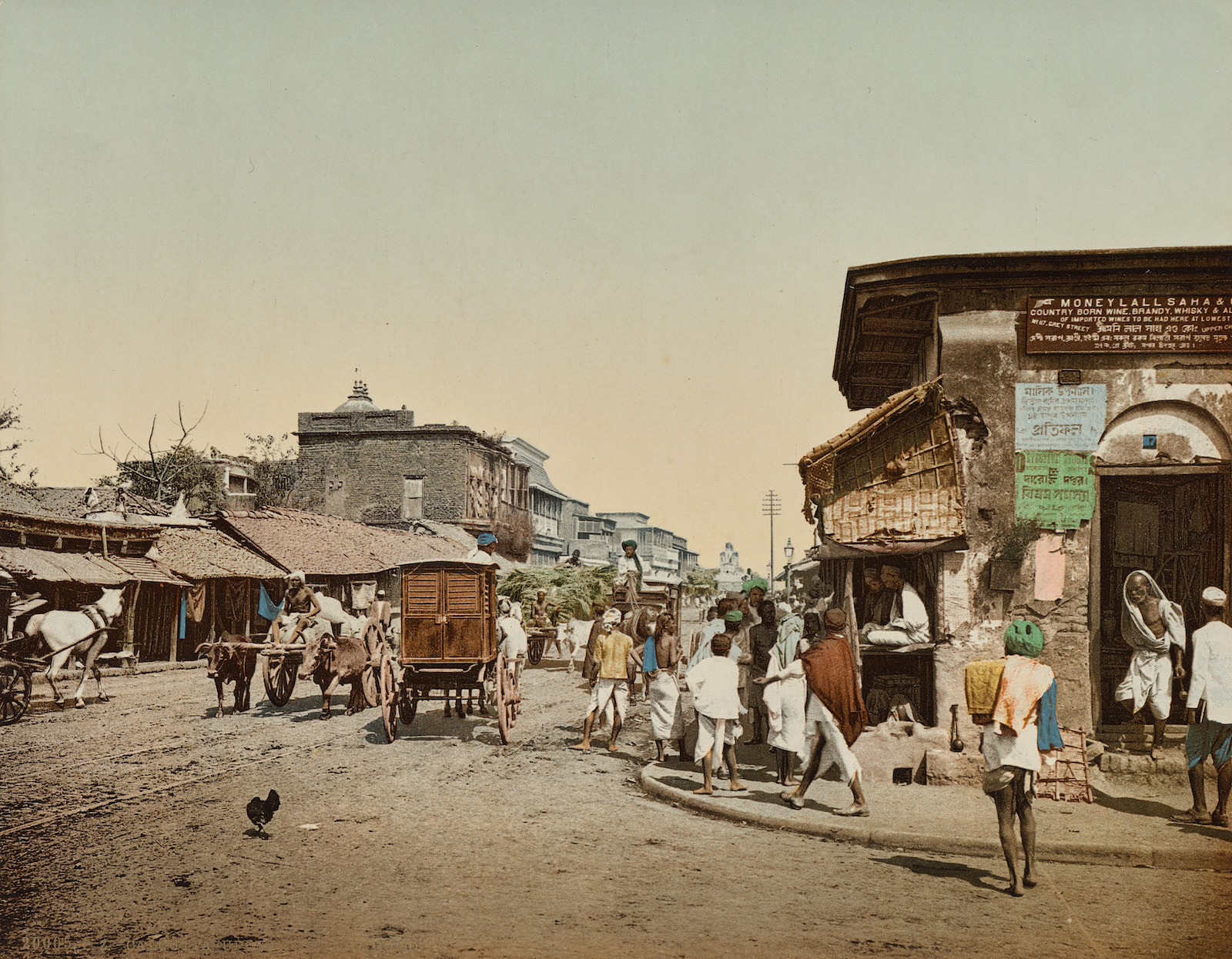

Thankfully, these defects are corrected in Chatterji’s book. In Modi’s India, it would be injudicious to gawk, as Guha did, in admiration at Indian democracy. Chatterji is more heedful of the developments that led India to its current illiberal impasse. Likewise, though they often appear in the form of the help in Chatterji’s household, the working class isn’t absent in these pages. Later chapters supply ample room to sex workers and snake charmers, among other subalterns. Shadows at Noon is a long but brisk read, enlivened by opinions on everything from textbook reform to travel advice: ‘If you can, visit Lahore’s Old City.’

What we have is a gently revisionist account of an enduring, if also ever-tottering, democracy. It is, on the face of it, a history not only of India but also its Muslim neighbours, though Pakistan and Bangladesh only have walk-on parts. Bengal gets top billing. South India and the mofussil are mostly ignored. But even as a history of India, the book has much to commend it.

Indian anticolonialism, Chatterji observes, had its dark side. Nationalists could twist themselves into pretzels, going so far as to decry the Age of Consent Act of 1891 as a colonial intrusion upon Indian values, of which marital rape apparently was one; the act had been prompted by the rape and murder of a 10-year-old girl by her 35-year-old husband. Refreshingly, there’s no halo around Gandhi. In Chatterji’s hands, the Mahatma comes down to earth as a befuddled soul perhaps too influenced by the Christian esotericism he imbibed in London. No radical, she writes, ‘Gandhi was instead an ally of capitalists and the caste order, a friend of patriarchy’.

Unusually for an Indian historian, Chatterji rightly lays the blame for Partition on the Congress, whose Hindu nationalists did much to push Muslims into the arms of the secessionist League. The creation of Pakistan was perfectly avoidable; both sides came close to burying the hatchet with the Lucknow Pact of 1916, and then again with the Cabinet Mission Plan 30 years later. Sadly, both proved inconclusive.

Chatterji has no time for the liberal pieties of India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Words were one thing, action another. In reality, he ‘thwacked down hard’ on the secular Left even as he tolerated the Hindu Right, admittedly on sufferance. Muslims were murdered wholesale in Hyderabad, and fired en masse from the civil service in the Hindi belt. Muslim leaders of opposition parties, the likes of Abdul Wahid Owaisi and Sheikh Abdullah, were locked up. The upshot? Small wonder that ‘at present, Hindu nationalism is triumphant’. It’s a sobering analysis aimed at ruffling the feathers of India’s ostrich-headed liberals, and welcome for it.

Less welcome is her pretension to novelty. Chatterji congratulates herself on her ‘fresh and profound argument’ – the similar trajectories of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh – though a long line of historians, starting with the brilliant Ayesha Jalal, got there decades before her. Moreover, while it is true that the three societies are ridden with the same malaises – poverty, the duplicity of socialist rhetoric and laissez-faire rule, the aversion to land reform, a love of red tape, the caste system – she bends the stick too far. The fact remains that there have been no military coups in India; generals have mounted eight of them in Bangladesh, six in Pakistan. The Indian state may be a shrivelled affair (with its 31 per cent public spending to GDP ratio), but compared with its neighbours (Pakistan at 21 per cent, Bangladesh at 14 per cent), it is positively ambitious. Arguably, Muslims in India have enjoyed better life chances than Pakistani and Bangladeshi Hindus since independence.

Britain’s ‘patriality’ laws, introduced in 1971 to curb coloured immigration, worked to Chatterji’s advantage: she was exempt from curbs on free movement as she could prove British ancestry through her English mother. She writes about this ‘privilege’ with remarkable self-awareness, that sometimes deserts her. Her PhD is turned into a ‘daring’ debut. She promises to introduce us to an ‘inquisitive young person’. Who might this be? You’ve guessed it.

There are also times when she channels Chips Channon, littering her prose with class markers. Gandhi’s assassination in the compound of a tycoon’s mansion is an opportunity to tell us that her husband ‘happened to be staying’ next door. She learns of the 1971 war between India and Pakistan through the family cook, her parents being too busy knocking back Angostura bitters. An observation about the conservative vegetarianism of the business diaspora prompts the off-hand disclosure that she’s in with families of the ‘kind who figure near the top of the Forbes Rich List’. We geddit.

Shadows at Noon: The South Asian Twentieth Century

Joya Chatterji

Bodley Head, 864pp, £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Pratinav Anil is the author of Another India: The Making of the World’s Largest Democracy, 1947-1977 (Hurst, 2023) and a lecturer at St Edmund Hall, Oxford.