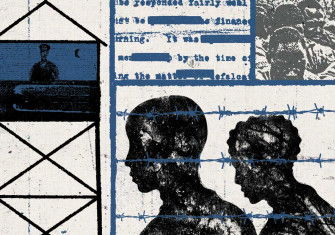

Legalised Lawlessness

The British Empire’s playbook of force.

Historians of the British Empire have a fondness for writing very long books. If the global scale of the subject helps to explain this tendency so, perhaps, does the lure of Gibbonian glory. Jan Morris’ trilogy, beginning with Heaven’s Command (1968) and concluding with Farewell the Trumpets (1978), traced an epic rise and fall narrative with colourful details and literary flair. Three decades later, John Darwin’s monumental The Empire Project (2009) followed the same trajectory in a comparatively scholarly mode, with an emphasis on high diplomacy, military strategy and political economy. The new magnum opus by the Harvard historian Caroline Elkins joins this tradition in some ways, while subverting it in others.

This is not a rise and fall story but a decline and fall story. Though an early chapter reaches back to the Black Hole of Calcutta and the impeachment trial of Warren Hastings in 1787, the bulk of Legacy of Violence covers the Second World War and the 1950s. An even more fundamental difference with previous accounts is that Elkins exploits the grandeur and sweep of imperial history to deliver a damning account of what the British Empire did to its subjects. As the title suggests, this is a book about the brutal repression meted out to anti-colonial rebels. The case studies include Arab, and later Zionist, insurgents in the Palestine Mandate alienated by British policy on Jewish settlement; ethnic Chinese Communists revolting against plantation capitalism and civic exclusion in Malaya; Greek Cypriot nationalists seeking political union with Greece; and landless Kikuyu dispossessed by British settlers in Kenya.

Legacy of Violence is the sequel to Britain’s Gulag, Elkins’ 2005 study of indefinite detention, forced resettlement and systemic torture during the Mau Mau Emergency in Kenya. Elkins later served as one of the expert witnesses in a lawsuit brought against the British government by elderly Kenyan survivors of the detention regime. The suit was settled in 2012 when the Foreign and Commonwealth Office agreed to pay nearly £20 million in damages, to issue a formal apology and to fund the construction of a memorial in Nairobi. Government lawyers were also forced to admit that reams of sensitive documents, removed from more than three dozen British colonies at the time of decolonisation, had been secreted in an intelligence facility in order to whitewash the legacy of empire. Many more records were destroyed as part of the same orchestrated effort. This book represents Elkins’ attempt to situate the abuses of the anti-Mau Mau campaign in a longer, deeper and wider history of institutionalised violence – precisely the kind of imperial history that imperial officials tried to suppress.

To tell this story, Elkins synthesises a huge quantity of scholarship, generously credited, along with archival discoveries from London to Jerusalem to Kuala Lumpur. (Unsurprisingly, given the passage of time, interviews with contemporaries play a less prominent role than they did in Britain’s Gulag.) Elkins tracks the practitioners of imperial violence who jumped from colony to colony as insurgencies flared. Peripatetic bureaucrats, police officers and army strategists carried with them an evolving script for squashing rebellion through nominally legal, but substantively illiberal means. By suspending the rule of law with expansive Emergency Regulations, the authorities licensed vast security operations, which rounded up thousands of vaguely defined ‘suspects’ at a time. Rewriting the statute book at a stroke also enabled the state to imprison individuals for years without trial; to convict and execute them with a minimum of procedural obstacles; to impose collective punishments on whole communities; to confiscate land, destroy homes, censor opposition and much more. This is the process that Elkins memorably describes as ‘legalised lawlessness’.

By mapping the movements of counter-insurgency planners on a sprawling canvas, Elkins makes it possible to see connections that might otherwise escape notice. She persuasively identifies Britain’s response to the Arab Revolt in 1930s Palestine as a pivotal moment of ‘convergence’ and ‘consolidation’ that set the template for future campaigns. Assembling in Jerusalem, grizzled veterans from Ireland and India compared notes on methods of torture, while civil authorities wrote the army a virtual blank cheque for repression. ‘Even at the time of the Jacobite risings in 1715 and 1745, no such powers were ever claimed by the armed forces of the Crown as are now claimed or recommended by the military authorities’, officials back in London observed. They nonetheless approved language which conferred ‘unfettered discretion’ on the British high commissioner in Palestine.

Without sanitising the violence perpetrated by anti-colonial rebels, Elkins casts them and their fellow travellers as heroic figures. She quotes poetically eloquent critiques of empire from Yeats, Gandhi, Padmore, Ngugi and others; the imperialists, meanwhile, speak mainly through bureaucratic memoranda and hollow speechifying. Even so, it is the unglamorous and arguably hypocritical architects of the late imperial security order who command centre stage in Legacy of Violence. At its core, this is the story of an administrative and military elite that exercised largely unaccountable power over huge swathes of the world’s population. In that sense, at least, Elkins’ book is not so different from traditional imperial histories as it might seem. The affective tone and moral focus have shifted dramatically; the subject matter less so.

If ‘legalised lawlessness’ is one of the key concepts in Elkins’ history, ‘imperial liberalism’ is the other. This nods to a huge body of recent scholarship attributing the damage inflicted by British rule to liberal ideology: its civilisational hierarchies and infatuation with progress, its pedagogical impulse to reshape cultures and societies, its faith in codification (to the point, even, of enshrining permanent or near-permanent exceptions to laws and constitutions). In some ways, British-style counterinsurgency offers almost a caricature of liberal ambition run amok. The colour-coded system used in Malaya and Kenya to track detainees’ gradual progression toward political reliability is a conspicuous example of this.

But does liberalism explain colonial violence as fully as Elkins implies? Too amorphous and capacious to generate a coherent doctrine on empire, the liberal tradition always sent conflicting signals about the means and ends of overseas rule. As Elkins notes, one of the most important theorists of legalised violence, the English lawyer James Fitzjames Stephen, was fiercely critical of what he saw as the confused sentimentality of classical liberal thought. By the same token, openly authoritarian regimes in other times and places have often employed enabling legal acts to legitimise their brutality. The recurring co existence of liberal forms and illiberal actions suggests that ideology can provide, at most, a partial explanation for violence.

Elkins’ argument for the ideological specificity of liberal violence marks a contrast with her first book, which invoked comparisons with the Holocaust and the Gulag to suggest that British imperialism had more in common with Nazism and Stalinism than conventional wisdom held. But Legacy of Violence still bears the influence of Holocaust historiography in one particular way; it navigates a tension between intentionalist and structuralist explanations, between the deadly drive of ideological visions and the callous improvisations of institutions plunged into crisis. Elkins’ achievement is to chronicle how makeshift responses to rebellion evolved into a chillingly standardised playbook for the use of force.

Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire

Caroline Elkins

Bodley Head 896pp £30

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Erik Linstrum is the author of Ruling Minds: Psychology in the British Empire (Harvard University Press, 2016).