History of a Memory

The curation, control and censorship of the life of the elusive St Ambrose.

In Milan, St Ambrose (c.339-97) is the ubiquitous anchor of civic identity. Every year the city honours its most deserving inhabitants with a prestigious gold medal named after the saint. A basilica, institutions and public celebrations such as the Ambrosian Carnival all bear his name. The La Scala Opera House opens its annual season on his feast day. The Ambrosian Library, founded in 1607, is home to Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus. Another Milanese institution named after Ambrose, the Banco Ambrosiano, came to international attention when, in 1982, its chairman Roberto Calvi – dubbed ‘God’s banker’ because of his ties to the Vatican – was found dead under Blackfriars Bridge in London. Yet despite Ambrose’s fame in Milan, in Christian memory he has been almost totally eclipsed by his contemporary, St Augustine. Augustine, author of the greatest Christian autobiography (Confessions), was taught by Ambrose and was inspired by him to convert to Christianity. While we know the various dramas of Augustine’s life, Ambrose is remembered as the man who baptised him.

Ambrose was much more than that. As Bishop of Milan he overcame formidable challenges by Arians (heterodox Christians) and set the tone for the relationship between church and state in the Middle Ages. Ambrose resisted Emperor Valentinian II and his mother Justina, who wanted him to hand over church buildings to the Arians. He strenuously defended what was believed to be correct doctrine. ‘The Church is God’s, and must not be given up to Caesar’, he wrote. Ambrose’s writings reveal him as a master of Latin eloquence and he is also remembered for his beautiful hymns.

Yet for all his achievements, Ambrose remains an elusive figure. He curated, controlled and censored his own image to such an extent that even the biography written of him by his close collaborator Paulinus does not reveal much about the man’s private life. In a 1994 book Neil McLynn warned that, when dealing with Ambrose, the biographical approach is ‘doomed to failure’. In Trace and Aura, Patrick Boucheron may have taken this specific warning as a point of departure; but Boucheron also cites the French literary theorist Roland Barthes, who argued that writing a sequential biography is always an ‘obscenity’ and a sham: ‘Any biography is a novel which dares not speak its name.’ Boucheron aims only to ‘assemble the history of Ambrose’s memory’.

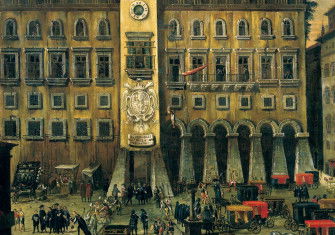

Boucheron examines that memory from the fourth to the 16th centuries. One of his case studies is an investigation of how Ambrose connected his memory with those of important martyrs of the Milanese tradition, such as Gervasius and Protasius, whose remains he buried in the Basilica of Sant’Ambrogio. Moving between centuries, Boucheron examines various moments in which Ambrose was remembered during the Middle Ages. In the Carolingian period, for example, he was memorialised through the Golden Altar in Sant’Ambrogio, a spectacular monument of ninth-century art depicting scenes from his life; it remains the liturgical centre of Milan today. A striking political use of Ambrose’s memory occurred in 1447, when the Milanese declared the short-lived Ambrosian Republic. The ‘last Ambrose’ was Cardinal Carlo Borromeo, another self-styled Milanese model bishop, who led the city through a period of vigorous Counter-Reformation in the 16th century.

The book’s strengths are also its weaknesses. When applied to history, postmodern theory is often valuable for pointing out what something is not: challenging unspoken assumptions and calling into question simplistic narratives. In this case, the critical thrust is that Ambrose’s biography is, strictly speaking, impossible to write and that his memory was diffused in non-linear ways. Postmodern theory is much weaker, however, at creating a coherent whole. While readers are given a wealth of intriguing detail about Ambrose’s memory, they are, in the end, left to their own devices to make sense of it. The book’s title, Trace and Aura, is not discussed until the Afterword, where Boucheron cites a passage from the German philosopher Walter Benjamin that inspired him. To some it might remain as cryptic as it is poetic: ‘The trace is appearance of a nearness, however far removed the thing that left it behind may be. The aura is appearance of a distance, however close the thing that calls it forth.’ Yet, as the book’s subtitle makes clear, Ambrose, by virtue of his memory, has lived various incarnations through the centuries and, in that sense, still lives today.

Trace & Aura: The Recurring Lives of St. Ambrose of Milan

Patrick Boucheron, translated by Lara Vergnaud and Willard Wood

Other Press 576pp £31.99

Buy from bookshop.org (affiliate link)

Stefan Bauer is Lecturer in Early Modern History at King’s College London and the author of The Invention of Papal History (Oxford University Press, 2020).