The Many Faces of Lady Jane Grey

Protestant martyr, prodigy of Renaissance learning, star-crossed lover, Hollywood heroine? The changing images of England’s Nine Days Queen of 1553.

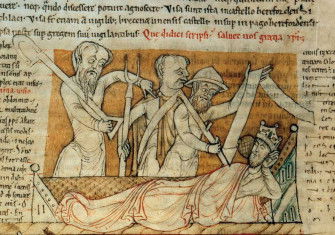

The story of Lady Jane Grey, the 'traitor-heroine of the Reformation', is perhaps the most poignant personal tragedy in British political history. The grand-daughter of Henry VIII's younger sister Mary and eldest child of the Duke and Duchess of Suffolk, this unworldly though resolute girl was flattered, favoured, and ultimately butchered on the block of political expediency. In a more settled age she probably would have lived a quiet, privileged life in the service of her family and her religion. She might have remained unscathed in the turbulent politics of the mid-sixteenth century but for the recklessness of her parents and the ambition of her father-in-law, the Duke of Northumberland, whose desire to make her queen upon the death of her cousin, Edward VI, ended in calamity. Yet in British constitutional history her fall from grace is not considered a national disaster. Here she is but a vapour, an insubstantial thing whose reign marks little of consequence save a brief delay in Mary's rule. What she might have become had Northumberland succeeded and her reign endured is pure speculation, except to say that if she had had the army which hedges kings the grounds for her claim to the succession would appear more convincing.

Dead before her seventeenth birthday, few historical characters are so often met yet so little known as Lady Jane Grey. Academic historians have tended to ignore her because of her constitutional unimportance and the problems of documentation. A few biographers have struggled to sift fact from fiction with mixed success, but a full-bodied portrait is impossible given the fragmentary evidence of her fragmented life. She is unusual in that artists and imaginative writers have played such a significant part in her reconstruction, or one might say more accurately her apotheosis. Many people have come into contact with her only through children's books, the theatre, cinema, Harrison Ainsworth's novel, The Tower of London, or Paul Delaroche's dramatic paintings. The iconography of Jane is a fascinating subject in itself.

Innocence offended is the stuff of legend. It is not misleading to say that Jane was a gifted girl, who, obedient to the wishes of her parents, married Lord Guildford Dudley, reluctantly became queen, was deposed by Mary Tudor, tried, found guilty of treason, and executed. This sketch suggests some of the elements of a fairy tale and is easily turned into one. The political confusion of the mid-1550s encouraged the fanciful, for many works by or about Jane were lost or purposely destroyed, perhaps even portraits. Rumour and speculation tilled the gap in the public record. Fantasy was given further licence in the decades immediately after her death because it was then impolitic to write about her. Whether by error or deliberate lie, myth fused with history in a way so irresistible that few writers checked the facts even when and where they were available. Who would wish to impugn a girl so highborn and so ill-used? Better to point a moral with her tragic tale. In life Northumberland put her in royal garb. In death others would dress her up to suit themselves. The mythic Jane who has emerged may be more to the public's taste than the historical Jane could ever be. Her many faces are fascinating, less for what they tell us about her than for what they tell us about ourselves.

Embellishments in the written record began to fill out the bare bones of Jane's story soon after Mary's death in 1558. Ballads were among the first to take her up. They depicted Jane and Guildford as blameless victims of parental miscalculation: 'The thyng our fathers toke in hande/ was neither his nor my consente'. (See F.J. Furnivall, Ballads from Manuscripts .) There was no mention here that Jane might have erred in accepting the crown or that Guildford wished to be king despite his wife's objections. Another ballad, in part Elizabethan, asked why innocence should be so wronged and ended with a bitter attack on Mary: 'For Popery I hate as death/ and Christ my saviour love', cries Jane. This was Jane as the embodiment of anti-Catholicism, a role she never deserted once Protestantism became fully established in England. It is very unlikely that a last minute conversion to Rome would have saved her, but to Protestants, especially puritans brought up on Foxe's Book of Martyrs , Jane died 'for faith and purity'. In their imagination she had a Christ-like holiness, and as such could do no wrong.

Jane the unrivalled scholar has been as appealing as Jane the Protestant saint. Her surviving letters suggest that she was academically gifted, though perhaps less than a genius. But most of her champions have been influenced less by her literary remains than by Roger Ascham, who mentioned her briefly in his work The Schoolmaster, published posthumously in 1570. That Ascham wrote about their meeting at Bradgate more than a decade after the event to give support to an argument about education is rarely mentioned. This, of course, does not make his description of Jane untrue, but one must suspect it as overblown. To Ascham she was the 'sweet and noble' lady, whose sole pleasure was the pursuit of knowledge and whose devotion to her gentle tutor Aylmer was in stark contrast to her fear of her cruel and overbearing parents. This portrait of a sad, thoughtful girl was especially attractive to Protestants, who varnished it and hung it beside Jane the martyr.

Many of the features which would be associated with Jane came together in what was the most fulsome tribute to her ever written, Sir Thomas Chaloner's Elegy . He wrote the poem while on diplomatic service in Spain in the early 1560s, but it was not published in England until 1579, years after his death. Written in Latin, it describes Jane as without peer in learning, soul, or beauty and comparable with Socrates for steadfastness in the face of death. Her 'murderer', Queen Mary, is savaged throughout. (Chaloner, though a Protestant, had been in Mary's employ.) Most intriguing is his assertion that Jane was pregnant at the time of her execution. Perhaps he knew something that his contemporaries did not, but it is more likely that a pregnant Jane was a deceit which made the 'marble-hearted' Mary appear all the more vile. While most of us do not expect historical accuracy from poets, it is interesting to note how often later champions of Jane would pull Chaloner's Elegy off their shelves and hold it up as truth.

One should not expect historical accuracy from playwrights any more than poets. In historical drama distortions of the subject are inevitable, for events must be condensed, complexities of doctrine and politics simplified. Moreover, vigorous narrative must take precedence over accuracy of detail if a play is not to be dull. With Jane dramatists have sought to serve their art by turning her into a romantic heroine. The first play to do so was by John Webster and Thomas Dekker. First produced in 1602 (published 1607) Lady Jane survives only in fragments, but enough remains to suggest that Webster was not writing with historians in mind. Much is made of the trial, for instance, in which Jane and Guildford 'my Dudley mine own heart' plead for each other's lives. (No defence was made in the actual trial where they both pleaded guilty.) On the day of their execution Jane laments: 'My dearest Guildford, let us kiss and part'. In this fiction Jane is executed first and her head brought to Guildford. The Duke of Norfolk concludes the play with the lines: 'And now their heads and bodies shall be joined/ And buried in one grave as fits their loves'. What little is known about their relationship would suggest that they were unlikely to have enjoyed one another's company, but in the theatre, as elsewhere, Jane and Guildford have been lovers ever since, perhaps in posthumous compensation for lives which seem too sad, too tragic, for us to bear.

At the end of the seventeenth century the playwright John Banks produced a more robust and sensual couple in his Innocent Usurper: or, the Death of Lady Jane Grey (1694, republished 1729). 'To see her is the blessing of the eyes', coos Guildford, 'but to lie by her panting side, and hear the beatings of her heart, love's softest language'. Not to be outshone Jane says of Guildford: 'The rose of youth/ the majesty of Kings/ Mildness of Babes, and fondness of a Lover, are all Angelically mixt in him'. In a fresh invention Jane accepts the crown only when Guildford threatens suicide by falling on his sword. As in Webster, a trial without a spirited defence is anathema, and the lovers plead for each other's lives. Drawing on Chaloner's Elegy , Banks alludes to an 'abortive infant' at the end of the drama. This fitted well with the strident anti-Catholicism of the play, which was likely to suit the prejudices of England under William III.

In the eighteenth century Jane takes on several fresh disguises, perhaps the most notable being her appearance in The Tragedy of the Lady Jane Grey written by the playwright and poet Nicholas Rowe. First performed in 1715 it was dedicated to the Princess of Wales. Ingenuously, Rowe admitted that he heightened. Jane's features 'to make her more worthy of those illustrious hands to which I always intended to present her'. The use of Jane to flatter patrons was not unique to Rowe: the poet Edward Young did it in his poem The Force of Religion; or, Vanquish'd Love, which he dedicated to the Duchess of Salisbury in 1714. Rowe's play is an encomium to a Tudor princess who might be confused for a Hanoverian, if only by a Hanoverian. The anti-Catholicism is cleverly interwoven with the plot, for Jane puts down her Plato and picks up the crown only to save English Protestantism. At the end of the play Mary offers Jane and Guildford life in exchange for a recantation of their faith, but London was not worth a mass and they 'bend their heads with joy'. The love story is elaborate. There is more than a hint that Jane was in love with her cousin Edward VI. Just as fantastically, Jane becomes a Commonwealth queen. Like Hugh Latimer and John Hales she would save England from social dislocation: 'My whole heart for wretched England bleeds'.

The works on Jane began to multiply at the end of the eighteenth century, taking on new forms and changes of interpretation. On the continent, La Place and Madame de Stael-Holstein, among others, found her story compelling. (The French and German writings on Jane are a subject in themselves.) In England a host of writers, though few of any distinction, adapted her for their own purposes. The reasons for her popularity in the early nineteenth century are complex, but the peculiar configuration of anti-Catholicism, cheap print, and a large female reading public certainly played a part. Chapbooks, female, magazines, 'histories', biographies, religious pamphlets, and children's books told her tale with didactic enthusiasm. One might expect from these works a higher level of historical accuracy than in the aforementioned plays, but most lack any spirit of genuine historical inquiry. Most of them appear content to enlarge on Ascham's The Schoolmaster , Chaloner's Elegy , or the works of partisan churchmen. Even Nicholas Rowe is trotted out by one 'biographer' as an authority on Jane.

We should not be too severe with these popular writers when many celebrated historians, who might have been expected to show more restraint, contributed their weight to the hyperbole and myth-making about Jane. Bishop Burnet, parroting the Protestant line, called her 'the wonder of the age' in his History of the Reformation (1679-1714). Oliver Goldsmith lifted this phrase for his History of England (1771): 'All historians agree that the solidity of her understanding, improved by continual application, rendered her the wonder of her age.' David Hume also depended heavily on Burnet and other Anglican worthies for his interpretation of Jane. In the History of England he added his authority to Jane's romance with Guildford. To Hume it was Guildford, so 'deserving of .her affections' whose entreaties persuaded her to accept the crown. Hume does admit that this was an error of judgement on Jane's part, but he is quick to excuse it. Few writers, however learned, were inclined to find fault with her. The Catholic historian John Lingard, writing in the early nineteenth century, was bold enough to find a blemish in her character (she liked dresses overmuch) and to remind her promoters that they seem 'to have forgotten that she was only sixteen.'

In England in the decades following the French Revolution Jane was taken up by the evangelicals, who were more interested in encouragements to practical piety than in impartial scholarship. Evangelical Jane is a remarkable concoction. Prim and tidy, she is not much seen on the stage in these years. Prose not poetry is her metier. Her faith is now legendary and resembles her execution dress, both spotless and both ready to be worn at moment's notice. Her promoters multiply her virtues and magnify them out of all proportion. As the Lady's Monitor declared in 1828, she inherited 'every great, every good, every admirable quality, whether of mind, disposition, or person'. Even the philosopher William Godwin, unremarkable for his piety but always in need of cash, wrote a hagiography of Jane for children in 1806 under the pseudonym Theophilus Marcliffe. To Godwin, Jane was 'the most amiable and accomplished woman in Europe' and 'the most perfect model of a meritorious young creature of the female sex to be found in history'. One wonders what Mary Wollstonecraft, his wife, would have made of all this.

Godwin contributed to the transformation of Jane into a model of female propriety and virtue suitable for the education of young ladies. One Memoir of the Life of Lady Jane Grey (1834) was explicit on this point. Written out of 'maternal feelings' it was hoped that Jane's 'character, conduct, and perseverance might create a sentiment of admiration, and, perhaps, some little emulation in the hearts of her children'. The Lady's Monitor agreed: 'What a model for the youth of her sex does this noble girl afford'. As an educational example Jane's scholarship comes to the fore. The literary works attributed to her show her to have a knowledge of English, Latin and Greek; but drawing on Chaloner's Elegy , Jane's nineteenth-century promoters had her the mistress of eight languages, including Hebrew, Chaldee, and Arabir. Rarely has a reputation for scholarship been so cheaply earned. Perhaps tearing that Jane would look a prig, which she must have done to many of her contemporaries, some writers neatly rounded off her education to include 'ordinary feminine' accomplishments. So this 'mild, humble, and modest spirit' was also distinguished for her skill in needlepoint and music, just like the ideal Victorian girl.

Stitching and praying, doing her lessons and practising her lute, Jane was not very sexy in the nineteenth century. The evangelicals had a weakness for heroines of romantic proportions, but they did not wish to emphasize the physical. There was no 'panting' at Guildford's side as in Banks's Innocent Usurper . The love between them here leans heavily toward conjugal affection, a tenderness bordering on brotherly and sisterly devotion. As one writer put it, the story was 'not a love-tale, and it would be degrading to indulge in sentimental effusions'. The approved version of Jane's marriage (see, for example, Lady Jane Grey: An Historical Tale , 1791) saw her as a comely housewife, devoted to her parents, her in-laws, and to the local community. No mention here that she and Guildford were not ideally matched, or that she was reported to have contracted a skin disease brought on by her worry that her mother-in-law was trying to poison her. Rather, one pictures the young couple in family prayers, or Jane and the Duchess of Northumberland arm in arm on their district visiting rounds.

Interpretations of Jane have always had implications for the way in which those around her are characterised. By the nineteenth century Jane had become too pure to be coupled with a libertine, too wise to be associated with a fool. Most writers recognised that very little was known about Guildford Dudley, but he had to be virtuous if Jane married him. So Guildford, who some evidence suggests was a wilful mother's boy, indeed a crybaby, became what was asked of him. In the nineteenth century this was typically the 'chivalrous' behaviour associated with his 'illustrious' birth. As the devoted couple must be innocent, villains were required to explain their tragic downfall and to exculpate them from guilt for their part in usurping the crown. Mary, of course, comes centre stage as an unfeeling bigot. So too does the Duke of Northumberland, whose evil designs are often highlighted. The fact that he converted to Catholicism before his execution was further proof of his perfidy and unsound mind to Protestants.

Probably the most widely read version of Jane's story has been William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London, published in 1840. As a romantic novel it marks a departure from the didactic, often religiously inspired works on Jane which preceded it. Often republished, it continues to be read by adolescents who enjoy romantic fiction and by a few academics who would have us believe that Ainsworth is an undiscovered Dickens. Adorned by Cruickshank drawings, The Tower of London is perhaps the most evocative treatment of Jane's world ever written. The plot is filled with giants, spies, and assorted villains, some historical, some legendary. Jane, who had put on height and glamour by 1840, is tall, beautiful, wise, majestic, and 'passionately attached' to the handsome and chivalrous Guildford. She is given a more rounded emotional life by Ainsworth than is usual, for all was not happy in the Dudley menage. In what might be seen as a lapse into something resembling the truth of their ill-fated marriage', the young couple are permitted a row, over the issue of Guildford's demand to be king. Jane refuses and Guildford walks out in a huff. The squabble is soon overtaken by events, however, as Mary enters the Tower in triumph.

Ainsworth treats Queen Mary fairly by the standards of his time and with more generosity than many eminent historians have been able to muster. Generously indeed, since his Mary pardons Jane and Guildford after their trial and releases them to live in retirement at Sion House. Here the impetuous Guildford plots his revenge and ever eager to wear a crown he joins Sir Thomas Wyatt's rebellion. Jane denounces the plot as futile, but she is unable to talk Guildford out of it. Unwilling to betray him she falls 'prey to grief almost to despair'. In the abortive rising Guildford is captured; Jane surrenders and pleads with Mary to spare his life. Now a pardon is conditional upon reconciliation with Rome, which neither Jane nor Guildford can contemplate. Sustained by their faith, they reject the entreaties of Mary's confessor Feckenham, declare their undying love to one another, and go to the block with dignity. 'The axe then fell, and one of the fairest and wisest heads that ever graced the human form, fell likewise.'

Dramatists returned to Jane in the 1880s. No fewer than three plays were published in that decade: Robert Buchanan's A Nine Days' Queen, produced successfully on the West End in 1880; The Earl's Revenge or Lady Jane Grey, by J.W. Ross, a five act verse drama (1882); and John Dudley, A Tragedy for Stage and Closet by Scriptor Ignotus (1886). This last work appears never to have been performed, but in some respects was the most interesting. In common with all the other plays about Jane, she is cast as a radiant girl whose face 'might well overthrow a world of hearts'. And as in several other versions Guildford presses the crown on her: 'What! Guildford's hand! – the index of my soul! Could that become the instrument of ill? Nay, then 'til Heaven speaks here – I am Queen.' The play is, nonetheless, a defence of Mary rather than a narrative of Jane's tragedy. Towards Jane, Mary is charitable in her instincts and tolerant in her views. As the play ends with the execution of Northumberland the question of Mary's responsibility for Jane's death is avoided. Even Northumberland appears human in this drama, which is unusual in avoiding the black and white moral references which feature in other versions of the tragedy. Perhaps this is why Scriptor Ignotus (presumably a Catholic) found it difficult to get Victorian theatre managers to accept it.

While popular historians and biographers continue to recreate Jane, it is likely that in future more people will come into contact with her through cinema or television. This process began in 1936 with the film Tudor Rose (Nine Days a Queen in America) directed by Robert Stevenson and starring Cedric Hardwicke as the Duke of Northumberland (called the Earl of Warwick throughout), John Mills as Guildford, Nova Pilbeam as Jane, and Sybil Thorndike as her nurse. Critics admired it for its poetic language, fine acting, and artistic integrity. A glance at the props and costumes alone refutes the publicity which called it 'unbending in regard to accuracy'. But there is some history in it, which is perhaps surprising when we consider that it concentrated the politics of 1547-54 into about seventy-eight minutes and aimed to sustain an entertaining and moving narrative. As history it is rather more accurate than any of the plays about Jane. Like most of them it cast Mary as an implacable fanatic; and, of course, Guildford and Jane are star-crossed lovers, though this is treated tamely and to little purpose.

The 1980s face of Jane may be seen in the film directed by Trevor Nunn, Lady Jane, which will be shortly on release. Produced by Peter Snell with a script by David Edgar and starring Helena Bonham Carter as Jane and Cary Elwes as Guildford, the story is played as a romance, set amidst a darkening world of domestic intrigue and national crisis. In her sensuality and political consciousness this Jane is reminiscent of her early eighteenth-century namesake, though attention is paid to her religious and scholarly inclinations. The large number of scenes in the film allows for the inclusion of historical incident and a good deal of what might be called historical effect. As with Tudor Rose there is more accuracy of detail than in the earlier plays, where, even had the dramatists wished to get things right, the constraints of staging were greater. But as Trevor Nunn has said, his film is essentially about the legend, written and directed with a knowledge of the historical Jane. Though visually beautiful, it aims to be a psychological portrait rather than an historical pageant, a narrative of the gradual destruction of an unworldly girl by forces beyond her control. This may capture the psychological truth about Jane far better than the host of former plays, poems, ballads and didactic writings. A later generation will have to judge whether this version is any less obviously the child of its time than earlier ones.

Frank Prochaska is a historical adviser on the film Lady Jane (1986), and author of Women and Philanthropy in Nineteenth-Century England (Clarendon Press, 1980).