Who Was the Real Henry III?

What makes someone a king? More importantly, what unmakes a king? Henry II’s experiment in co-kingship saw one Henry III fall and another rise.

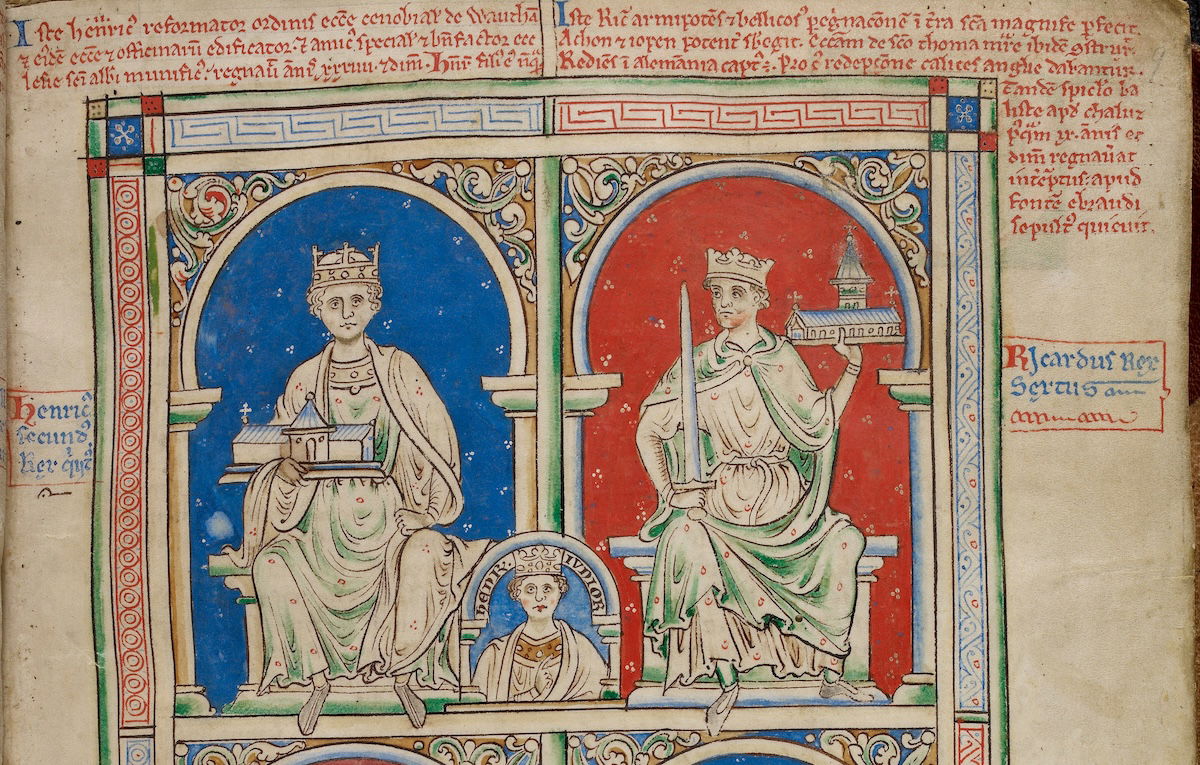

Born in 1155, Henry was the eldest surviving son of King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. On 14 June 1170, when he was 37 and his son 15, Henry II had his son crowned as Henry III. This experiment with co-kings proved a short-lived failure. The young Henry was afforded less authority than his father, which, combined with his lack of lands and income, led him to rebel repeatedly. After Henry II’s death, English kings returned to designating, but not crowning, an heir.

The idea of associate kingship is simple: the monarch crowns their designated heir during their lifetime to ensure the succession after death and prevent a power vacuum. Associate kingship was a feature of rule in several European kingdoms and was the norm in France, with the Capetian dynasty (987-1328) crowning associate kings until Philip II Augustus in 1180. These junior kings acted like apprentices, learning how to rule ‘on the job’, by jointly presiding over royal councils, pronouncing on legal disputes, and leading military expeditions. The system proved remarkably successful in ensuring a smooth succession in a turbulent kingdom.