The Warsaw Ghetto’s Underground Library

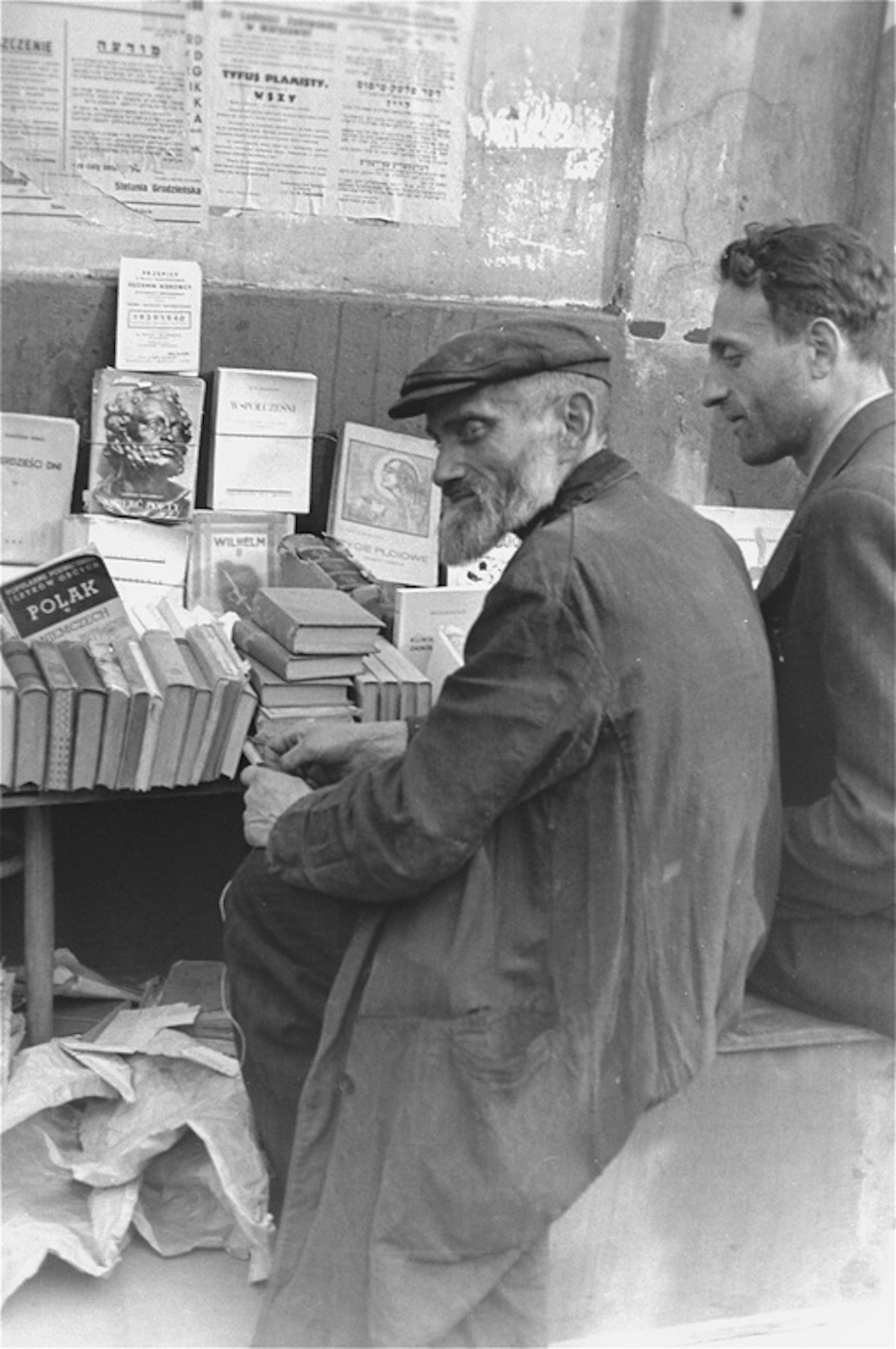

As the Nazis enclosed Warsaw’s Jewish quarter in a ghetto, a librarian set up a secret children’s library.

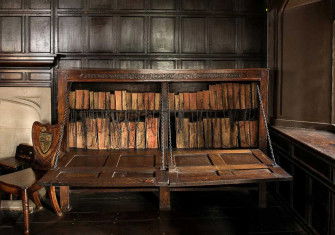

When the Nazis occupied Warsaw in September 1939, anti-Jewish laws were immediately promulgated. Among them were laws limiting access to books. Lending libraries were closed in the Jewish quarter and Jews were forbidden from using public libraries.

A ghetto was established in the autumn of 1940, enclosing nearly half a million Polish Jews into an area of just 2.4 per cent of the city, surrounded by ten-foot brick walls. Their official daily rations consisted of a meagre 184 calories. An estimated 83,000 died from starvation in less than two years and hundreds of thousands were deported to Treblinka extermination camp during the summer of 1942.

While many Jewish leaders and relief organisations in the ghetto were primarily concerned with providing food, clothes and shelter in response to overcrowding, hunger and Poland’s bitter winters, there were some who addressed another hunger.