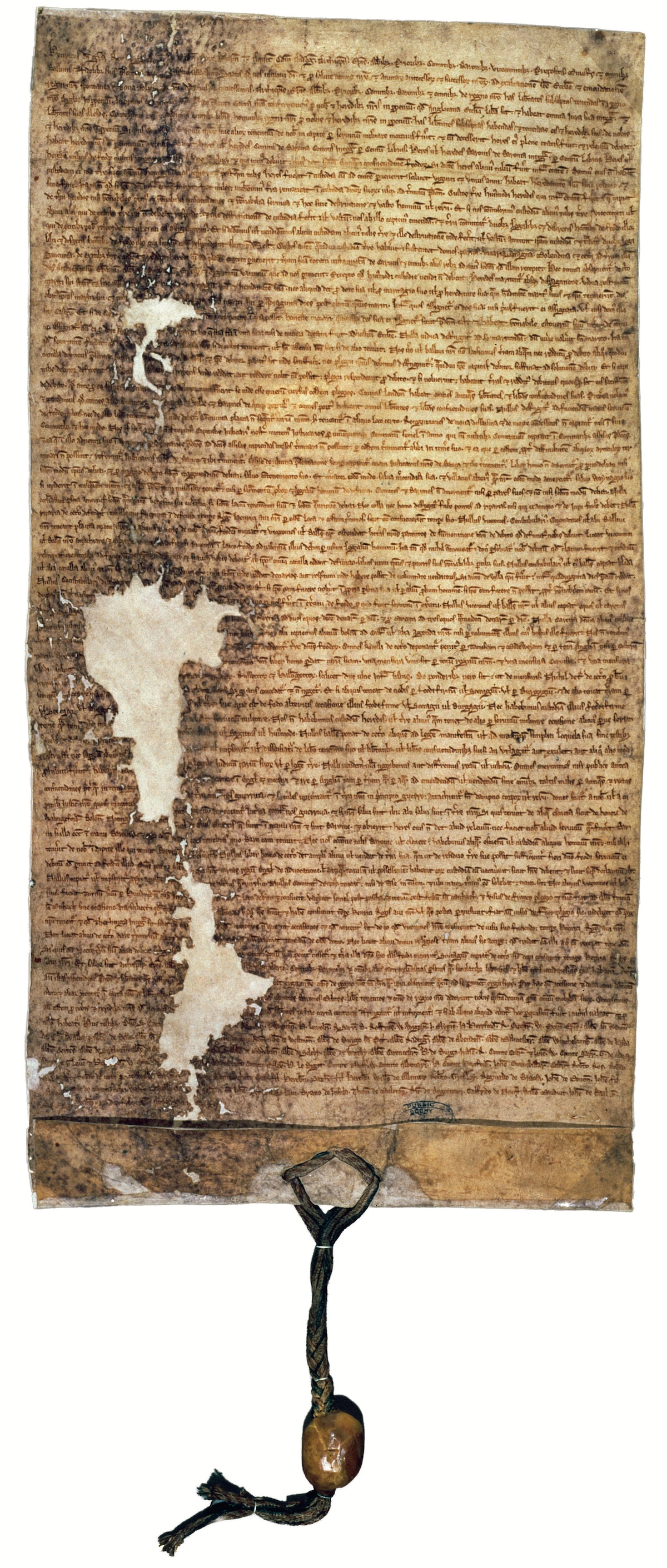

The Real Magna Carta

Less famous than its 1215 predecessor, the Magna Carta of 1225 held the true power.

The Magna Carta of 1215 is celebrated globally as the foundation of modern liberties and rights for its stipulation of equality before the law and its placing of monarchs and rulers under it. However, significant as the 1215 charter is, the document sealed in June of that year between King John and his rebellious barons was a prototype, far from the final version set out in law. That came ten years later in 1225.