Following Threads to Colonial Barbados

Two rare textile discoveries connect 18th-century Barbadian schoolgirls to England.

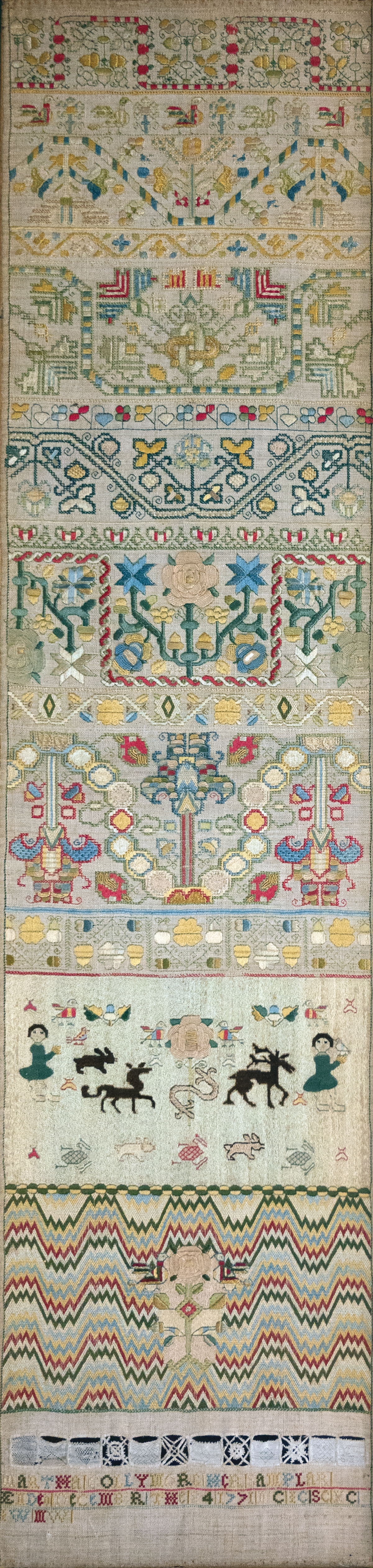

Samplers, pieces of embroidery made to practise or demonstrate needlework stitches, were an important part of girls’ education for centuries. In Britain, girls stitched samplers from the 17th to the early 20th centuries, gaining skills such as the literacy, counting, and dexterity they would need to be successful wives, mothers, and mistresses of households or, if they needed to earn a living, effective domestic servants or participants in the textile trades. Many girls throughout the British Empire – in India, Australia, and Sierra Leone – were also made to stitch. Some were sent to British missionary schools and made to make samplers with Christian messages, while other girls embroidered at home or at female academies. Though occasionally a piece of needlework made in Britain’s Caribbean colonies in the 19th century comes to light, finding examples from the 18th century is like finding a needle in a haystack, due to neglect, environmental conditions, or very few being made in the first place. However, despite the odds, two 18th-century Barbadian samplers have recently been identified in British collections.