Was there a Women’s Renaissance?

We ask four historians whether the great advances of the Renaissance were extended to women.

‘Don’t be born a woman in Florence, if you want your own way’

Dale Kent, Professorial Fellow, School of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne and author of Cosimo de’ Medici and the Florentine Renaissance (Yale, 2000).

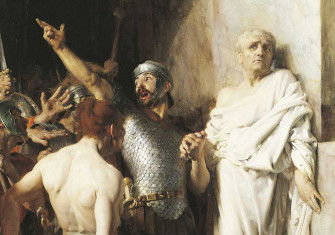

The Renaissance was a rebirth of interest in classical Greek and Roman culture, submerged in the rise of medieval Christianity. Historians, responding to the magic of names such as da Vinci and Michelangelo, inserted this concept between medieval and modern eras, artificially extending it to social and economic developments.

While Lorenzo de’ Medici fostered the creativity of classicising artists, writers and thinkers, his sister Nannina reflected bitterly, after a fight with her father-in-law: ‘Don’t be born a woman in Florence, if you want your own way.’

Arguably one overarching lesson of history is that the best time to be born a woman will be tomorrow. As always, and everywhere, women’s experience in the Renaissance depended upon the regulation of their sexuality, their economic and political roles, their education and the expectations of their culture.