Yorkshire’s Luddites: At War with the Future

In 1811 skilled textile workers in Britain attacked factories and factory owners to defend their livelihoods. By the time the Luddite cause hit Yorkshire in 1812, it had become a genuine mass movement.

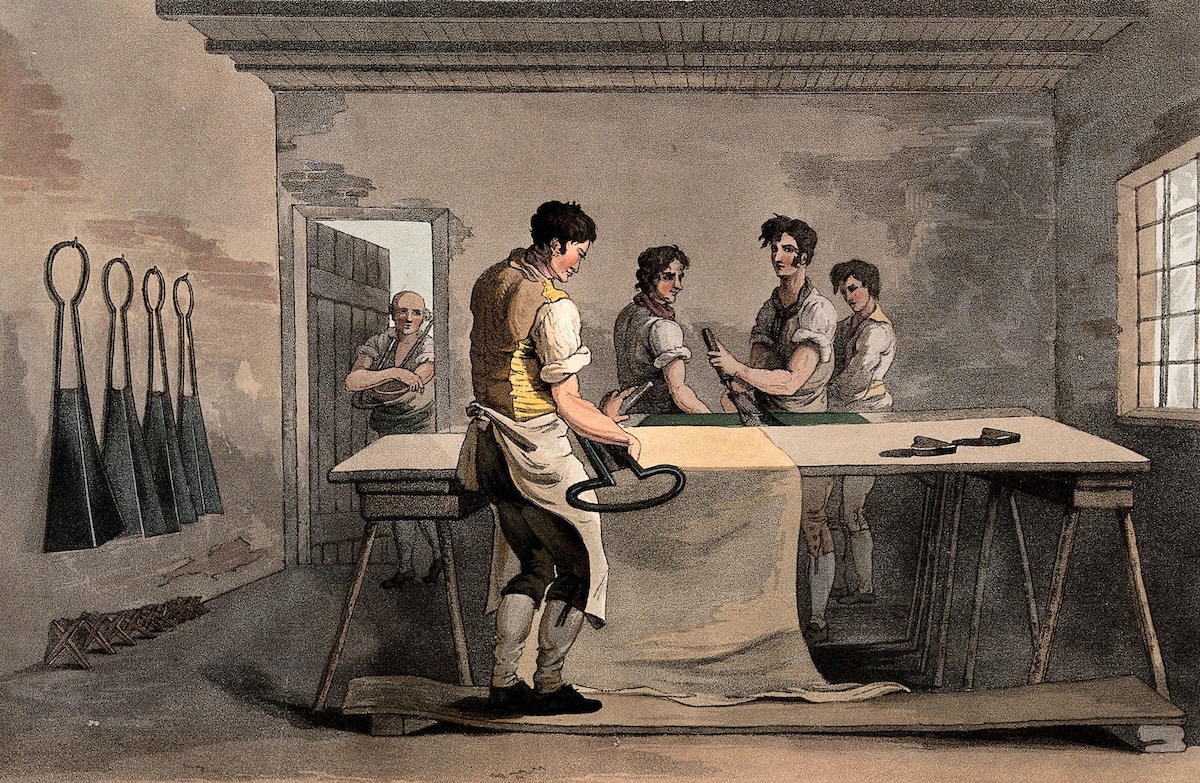

The term Luddism has entered everyday usage as an expression for hostility to technology and progress, but the original phenomenon was far more nuanced and sophisticated than that. The Luddite disturbances of 1812 were part of a much older tradition of food rioting and political unrest and stemmed also from the precise status of certain forms of skilled labour in English law and society. The precedent for highly skilled craftsmen reacting vigorously, and occasionally violently, in defence of their status and interests dates back at least to the 1563 Statute of Artificers, a body of law that governed much of the market for skilled labour, and perhaps as far back as the Statute of Labourers of 1381. When we consider that the cloth industry had seen large-scale technological innovations going back to the introduction of the watermill in the 13th century it becomes much harder to argue that the Luddites of 1811 and 1812 were motivated by a knee-jerk resentment of technological innovation.