Spain’s Ethnic Cleansing of the Muslim Moriscos

The expulsion in 1609 of more than 300,000 Spanish Moriscos – Muslim converts to Christianity – was a brutal attempt to create a homogenous state.

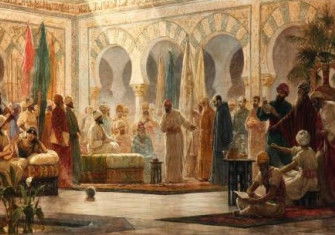

In April 1609 one of the darkest chapters in Spanish history unfolded when the Habsburg king Philip III secretly authorized the expulsion of the entire Muslim population of Iberia. Over the next four and a half years, approximately 300,000 men, women and children known pejoratively as ‘Moriscos’ or ‘half-Moors’ were forcibly removed from Spanish territory in what was then the largest ethnic deportation in European history. In its combination of bureaucracy and deployment of military force to remove an unwanted population, the expulsion anticipated the more recent phenomenon of ‘ethnic cleansing’. Today, at a time of tension between the Islamic world and the West, the 400th anniversary of the expulsion is a fitting occasion to recall this traumatic episode.