Soviet Super Sniper Lyudmila Pavlichenko

Lyudmila Pavlichenko, the ‘Guerrilla Queen’ of Soviet Russia, became a role model for women in combat during the Second World War.

In 1942, Lieutenant Lyudmila Pavlichenko, a Soviet frontline sniper, was sent on a mission to convince US and British allies to open up a Second Front against Hitler’s forces. The ‘Guerrilla Queen’ was feted at sites of bomb damage, munitions factories and shipyards, entertained at the White House and in Whitehall, addressing thousands. Her arrival in Washington DC coincided with a historic moment of American-Soviet friendship, even while the press found the female sniper, with her claimed tally of 309 German kills, rather shocking. She sneered at their questions about make-up and clothes, asked why women factory workers were paid less than men and protested when barred from boarding a Royal Navy warship.

But Pavlichenko, whose frontline experience had earned her the right to such plain speaking, was actually the latest in a long line of Russian female combatants. Journalists had already forgotten the earlier fascination with the first Women’s Battalion of Death, organised by Maria Bochkareva in 1917. The women’s rights activist Florence Harriman had funded Bochkareva’s visit to the US capital where, in her military uniform, she had urged President Woodrow Wilson to finance an anti-Bolshevik military expedition. Although Bochkareva’s efforts were unsuccessful – the Bolsheviks executed her in Siberia in 1920 – she had served as a powerful figure for the suffragettes, who believed that women’s participation in combat would ensure their right to political engagement.

During the Second World War, the British government would employ the Soviet female combatant in their propaganda to encourage its own women to support the war effort. While the Americans appeared less enthusiastic about women’s active military participation and regarded Pavlichenko with a mixture of awe and fear, she reminded them that Soviet female soldiers were not a ‘novelty’. In the US Communist Party magazine Soviet Russia Today, Pavlichenko wrote:

We [women] have a tradition, too, to live up to. There was [Nadezhda] Durova, the Russian woman guerrilla who fought against Napoleon’s invading armies in 1812, and Dasha Sevastopolskya who fought in the heroic defence of Sevastopol in 1854-55. So in today’s war our women have carried on these traditions – and added something.

That ‘something’ may have been a bracing new form of womanhood that Pavlichenko appeared to embody and which would be required to win the war. Pavlichenko, who one reporter described as ‘the first Amazon of the Red Army to visit the capital’, began her tour as Britain and America were gauging women’s potential for combat. Journalists struggled to reconcile the young, well-scrubbed Russian woman with the expert killer who bristled at questions about whether ‘girls wear lipstick at the front line and what colour do they prefer’ and ‘what colour does Lady Pavlichenko prefer and what colour does she like?’ Equally objectionable were references to her ‘high Russian boots’, ‘scarlet-trimmed khaki uniform’ and a figure which was considered ‘a little plump, like most Russian women’.

Natural combatants

Pavlichenko disliked the trivialisation of her military career and, by implication, of all Soviet women who had enlisted en masse to defend their country. When asked in Chicago why she had chosen such a profession, Pavlichenko retorted with a reference to the Second Front: ‘Gentlemen, I am twenty-five years old and I have already managed to kill 309 of the fascist invaders. Do you not think, gentlemen, that you have been hiding behind my back for rather too long?’ She implied that women were taking men’s natural role as combatants, a situation which would be remedied when more of them enlisted.

In reality, Pavlichenko’s weapons training had begun before the war, along with thousands of other Soviet schoolgirls, through a paramilitary sports organisation. When the Germans invaded, Pavlichenko ‘resorted to all kinds of tricks to get [into the army]’ and served first in a ‘destroyer squad’ to dispose of German paratroopers with the Red Army’s 25th Rifle Division. She opened her sniper’s tally during the Defence of Odessa, which took place during the early phase of Operation Barbarossa and, despite being wounded, soon increased it to 187. After Odessa had fallen, she spent a further eight months defending Sevastopol, where, with her partner (a crucial relationship as snipers trained and operated together), she destroyed an enemy observation point and regularly fought duels with German snipers. Her division was decimated but she survived, albeit wounded, to be evacuated by submarine to Novorossiysk.

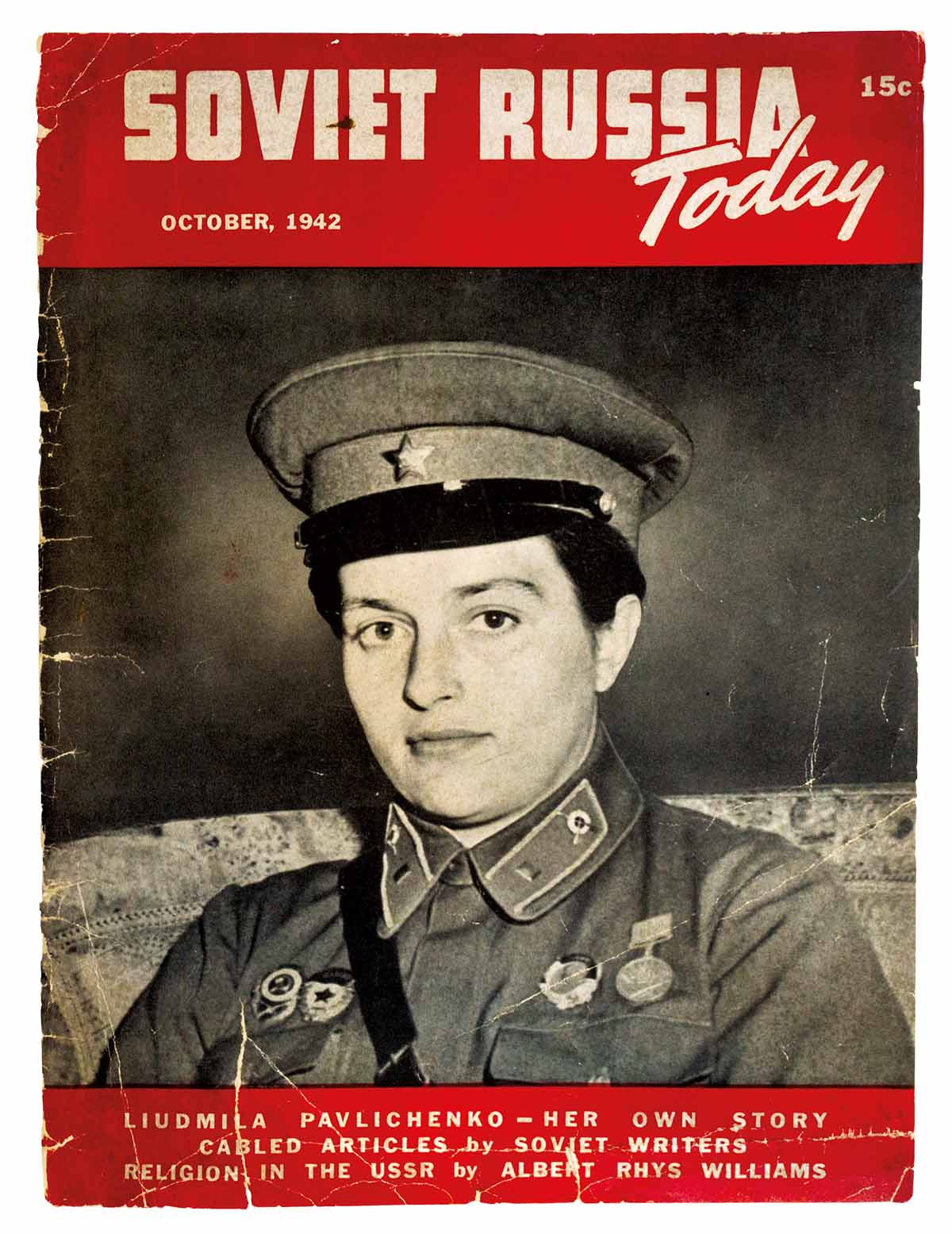

Pavlichenko’s feats seemed such a pure form of female patriotic sacrifice that they won her not only the friendship of Eleanor Roosevelt, who hosted her at the White House, but other celebrities on her tour of America. Paul Robeson sang for the Soviet delegates and, at a reception, Charlie Chaplin remarked as he kissed Pavlichenko’s fingers: ‘It’s just incredible that this little hand has killed Nazis, has scythed them down by the hundred, without missing, at close range.’ She was featured on the cover of Soviet Russia Today, with biographical details that conformed to ancient female warrior tropes. In childhood, she was, ‘a tomboy and rather unruly in the classroom ... I was keen on sports of all kinds, and played all the boys’ games and would not allow myself to be outdone by boys in anything. That was how I turned to sharpshooting’. The article urged Americans to support a ‘Second Front’, thus ensuring an enduring international friendship, which was immortalised by the folk singer Woody Guthrie in his 1946 song ‘Miss Pavlichenko’.

When the delegates landed in London, the journalists were as ready for this ‘Red Army girl sniper’ as she was for them. At a press event where she reviewed a Home Guard detachment on 5 November, she anticipated the same ‘silly questions’ she suffered in America so warned: ‘I wear my uniform with honour ... It has been covered with blood in battle. It is plain to see that with American women what is important is whether they wear silk underwear under their uniforms. What the uniform stands for they have yet to learn.’ She hoped that British women would prove more sensible.

Role model

In fact, the British government’s efforts to encourage their own women to support the war effort included exploiting images of Soviet women such as Pavlichenko. As the historian Chloe Ward has found, they appeared in propaganda posters, documentary shorts, theatrical features, radio broadcasts and books, supporting institutional calls for women’s self-sacrifice. Pavlichenko even appeared as a character in the 1944 comedy Tawny Pipit. ‘Lieutenant Olga Bocolova’, based on Pavlichenko, sings ‘The Internationale’ alongside Nancy, a member of the Women’s Land Army. It was a clever approach since Pavlichenko, during her 1942 tour, had already won women’s admiration.

They thronged to hear the Red Army sniper. When she reviewed the London Home Guard, the Northern Daily Mail noted that ‘every window in the Ministry [of Information] was crowded with girl clerks anxious to catch sight of the Russian woman soldier’. Propaganda had primed them to admire this liberated Soviet woman, who, on factory visits supported women workers’ right to equal pay, disapproved of being barred from a naval ship and, in Manchester, argued for lifting the ban on training women in arms. After visiting a London Bridge fire station, she suggested that Britain’s women ‘will, if necessary, fight shoulder to shoulder with the men as the women of Russia have done’.

Female readers of the Daily Record were invited to draw inferences about their potential for the services. Typical was an RAF recruitment advertisement that ran alongside the coverage of Pavlichenko’s factory visit in December 1942. Under a photo of a female mechanic, the strapline read: ‘These girls know their aircraft backwards after a few months’ training. And they all love the work ... It’s a grand job, responsible and fascinating: and you get plenty of chances to fly.’ British women now had opportunities to emulate their allied heroines, despite the unequal pay.

Although British journalists asked fewer questions about clothes and make-up, they still emphasised Pavlichenko’s ‘feminine’ qualities. The Manchester Evening News complimented her for ‘smok[ing] a cigarette more gracefully than a Mayfair debutante as she walked amid cheering crowds of girl workers to her car’. The Yorkshire and Leeds Intelligencer described her as ‘no strapping giantess’, but ‘good-looking with aquiline features and a flashing smile’, while a Liverpool Daily Post columnist noted that ‘she is ... undoubtedly attractive in her khaki uniform with its red to the collar and her shiny Russian boots’. Pavlichenko observed coolly the media’s reductive attitude, writing: ‘I am looked upon a little as a curiosity, a subject of newspaper headlines, for anecdotes.’

However often the press evoked debutantes, playful smiles and those shiny Russian boots, many remained profoundly unsettled by Pavlichenko, especially her attitude towards killing. Elizabeth Tenney was a student at the University of Washington, Seattle in 1942 when she hosted Pavlichenko at her sorority house. Although Pavlichenko was travelling with Eleanor Roosevelt and a ‘band of foreign students’ who had equally incredible experiences of war, it was the Russian sniper’s testimony that haunted Tenney. As she recalled:

The Germans had killed her husband and young children and wiped out the rest of her family. She had picked up a rifle and taken to the woods to stalk Nazi soldiers. One by one she killed some 309, sometimes hiding in the woods all night to get a good shot. By now she had killed more enemy soldiers than any other individual Russian and had received the highest medal for bravery from the Soviet government.

At a White House reception, Pavlichenko told a similar story when Mrs Roosevelt asked how, as a woman, she could shoot Germans whose faces she had seen in her rifle sight. She replied, ‘I have seen with my own eyes my husband and children killed. I was next to them’. The New York Times quoted Pavlichenko’s explanation of her ‘complicated emotions’ in combat: ‘The only feeling I have is the great satisfaction a hunter feels who has killed a beast of prey.’ It was an experience shared by other female snipers such as Anya Mulatova, who overcame her initial squeamishness to happily bayonet bloated German corpses ‘to let the gas out’. But perhaps, for a Western audience, the detail of avenging her husband and child’s death served to soften what seemed a ruthless quality that women rarely exposed in public.

Poster girl

Soviet military authorities probably chose Pavlichenko because she satisfied particular propaganda requirements: she was a sniper, an authentic representative of Communist youth and an articulate university student with links to the security services through her father. But her biography would need massaging. Although she had been a student, in 1941 she was also a single mother with a son, Rostislav, born in 1932, when she was 15 and married to a fellow student. The couple soon divorced and Rostislav was raised by his grandmother, which allowed Lyudmila to work, study and eventually to become a sniper. So Pavlichenko had lost neither husband nor child to the Nazis when she volunteered for military service – only two of the many details altered for public consumption.

Whatever her influence on British or Soviet female recruits, Pavlichenko, who died in 1974, has been immortalised in popular culture as an exceptional woman warrior. But like so many of the 800,000 women who served in the Red Army during the war, her legacy was highly fictionalised with a Russian film, The Battle for Sebastopol (2015), and a memoir translated into English in 2018, Lady Death. The brutal reality of women’s wartime experience and its painful aftermath would be silenced until relatively recently. Svetlana Alexievich, whose 1985 history The Unwomanly Face of War finally gave voice to those female veterans, has described their collective experiences as exposing the ‘male culture which legitimises war ... [It] is a monstrosity, a form of cannibalism’.

Julie Wheelwright is the author of Sisters in Arms: Female Warriors from Antiquity to the New Millennium (Osprey Publishing, 2020).

Further Listening

Julie Wheelwright in conversation with History Today editor, Paul Lay: