Roger Casement’s Heart of Darkness

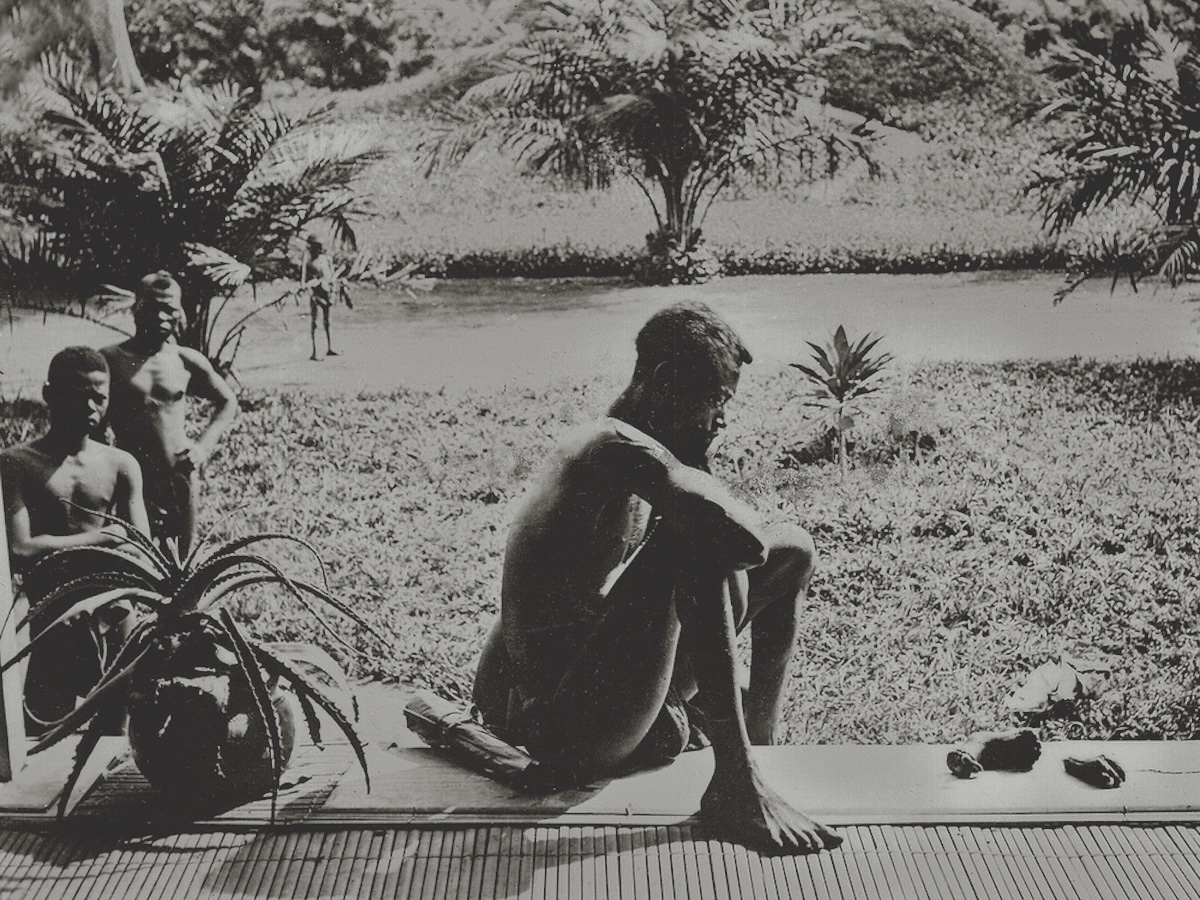

The grim reality underlying Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness echoed the growing moral outrage over the murderous rubber trade. For Roger Casement, it became a moral crusade.

In the spring of 1899, when Heart of Darkness was serialized in Blackwood’s Magazine, its author, Joseph Conrad, could scarcely have predicted that he had penned one of the most provocative and controversial literary works of the next century. For a hundred years now this short novel has been a window through which Europeans have glimpsed the scramble for Africa by their empire-forging ancestors. Behind Marlow’s river journey in search of Kurtz lie the great conflicts that seethed beneath the jingoism of Empire. The struggles between civilisation and savagery, nature and progress, cannibalism against culture, Christianity versus magic: all these opposites and others battle in the dense undergrowth of the narrative. Heart of Darkness was one of the earliest novels to attack concepts of Western progress and question dubious social Darwinist attitudes that were used to justify many brutal facets of Empire-building.