A Patriot For Whom? Benedict Arnold and the Loyalists

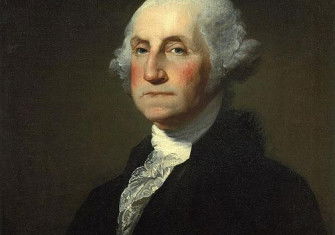

The dilemmas of allegiance posed for Americans by the outbreak of war with the British crown led Benedict Arnold, 'the most brilliant soldier of the Continental Army’, into the Loyalist camp.

In 1776 no less than one in five of all North Americans (including almost all Canadians) stayed loyal to George III (and in so far as many of them refused to take an oath of allegiance to the new regime, when required to do so, state by state, they were traitors to that state, if not yet to the non-existent 'nation'). At least 19,000 Americans enlisted in the King's service; at one time or another, there were fifty-six Loyalist units or 'associations' organised, though very rarely at full strength (and with many repeat enlistments). At least twenty-one of these units took the field with an average strength of a few hundred men each. General Howe on landing at Staten Island, in July 1776, was swamped by the numbers of volunteers, and the King's American Regiment went on to play a major role in British military history. By 1780 the 'Provincial Line' had a strength of 10,000. Eighty thousand Loyalists emigrated in or by 1783, and over 5,000 as 'the American sufferers', filed claims with the British Government, for losses of land, homes and jobs.