Lettow-Vorbeck: The Uncatchable Lizard?

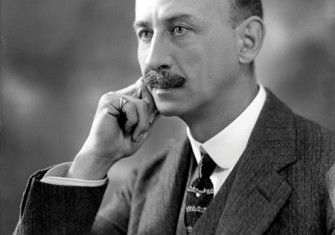

The German First World War commander Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck has been described as the 20th century’s greatest guerrilla leader for his undefeated campaign in East Africa. Is the legend justified?

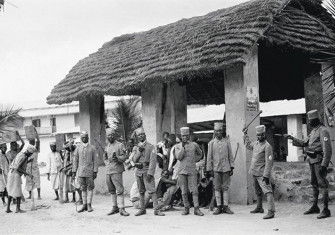

Grainy black and white film of March 13th, 1964 shows ranks of sombre middle-aged men gathered in a cold Pronzdorf cemetery. Many are uniformed soldiers. Two elderly Africans walk behind the coffin, dignified in their fez caps. Kai-Uwe von Hassel, the then West German defence minister, reads a eulogy. It is the funeral of Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, a First World War general who won the respect of Allied adversaries and was perhaps Germany’s last great military hero. Von Lettow’s exploits are still taught as case studies in US military colleges, where instructors present him as the 20th century’s greatest guerrilla leader.