How The West Was Lost

The expansion of the United States in the mid-19th century had a catastrophic effect on the Native Americans of the Great Plains.

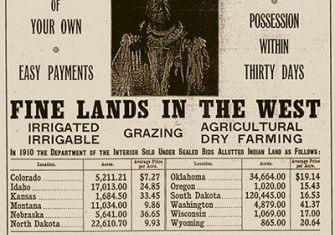

At the beginning of the nineteenth century the United States neither owned, valued nor even knew much about the Great Plains. This vast tract of grassland which runs across the centre of the continent was described as the ‘Great American Desert’, but by the end of the century the United States had taken it over completely. As the ‘new Americans’ (many of them black) pushed the frontier to the west, they established their culture at the expense of that of the indigenous peoples, then known to the incomers as ‘Indians’.