The Survival of the Nefarious Slave Trade

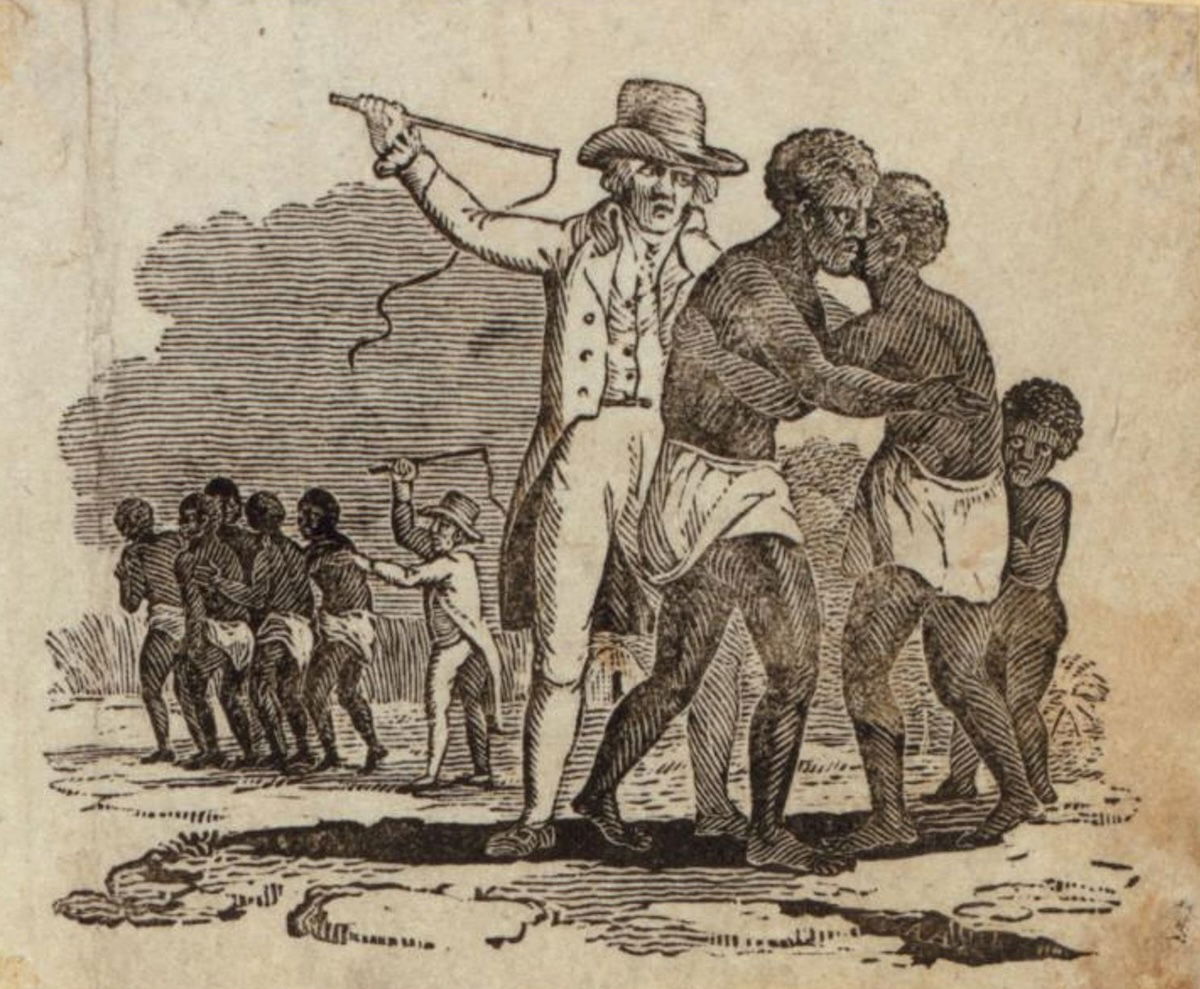

British traders in enslaved Africans found ways around the Slave Trade Act of 1807, while commerce flourished through the import of slave-grown cotton.

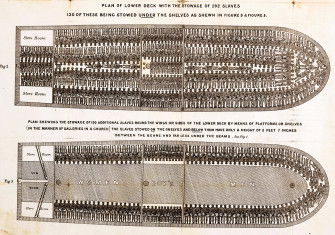

Within days of the 1807 Anti-Slavery Act coming into force, British slave traders were already deploying a number of ruses to circumvent it – as it had taken some twenty years for Parliament to pass the Act, there had been plenty of time to figure these out. In 1810 reports that British slavers, sailing under foreign colours, were still actively involved in the trade led the politician and reformer Henry Brougham to present a new bill to make the 1807 Act more effective.

Negotiations with some other European countries engaged in the ‘nefarious trade’ resulted in agreements to stop trading, or to stop trading at particular latitudes – after all, Britain did not want other countries to increase their profits from cheap slave-produced goods. Even the Prince Regent participated in this international pressure.