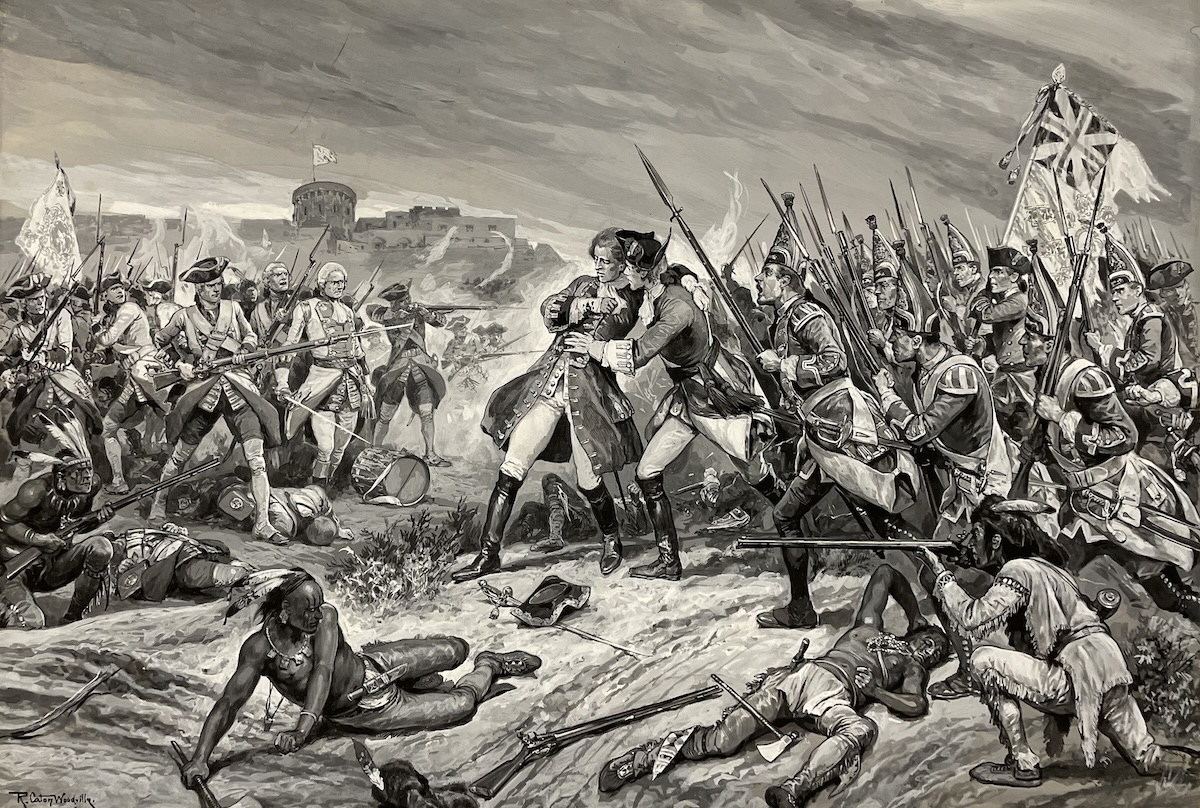

General Wolfe’s Men in Quebec

In 1759 a British army under General James Wolfe won a momentous battle on the Plains of Abraham. A neglected ingredient in Wolfe’s dramatic victory was the professionalism of the army he had helped to create.

Two hundred and fifty years ago a British Army under General James Wolfe won a momentous battle at Quebec. The outcome has been seen as a fortuitous springboard to Empire, the result of luck more than leadership. But, as Stephen Brumwell argues, a crucial – and neglected – ingredient in Wolfe’s dramatic victory was the professionalism of the army he had helped to create. On the morning of Wednesday, September 12th, 1759, on the St Lawrence River some 11 miles from the fortified city of Quebec, Major-General James Wolfe issued final orders to his army. They included an appeal to the troops’ patriotism and esprit de corps: the 32-year-old Wolfe urged officers and men alike to remember ‘what their country expects from them, and what a determined body of soldiers, inured to war, is capable of doing against five weak French battalions mingled with disorderly peasantry’. Wolfe’s emphasis upon his redcoats’ professionalism is significant.