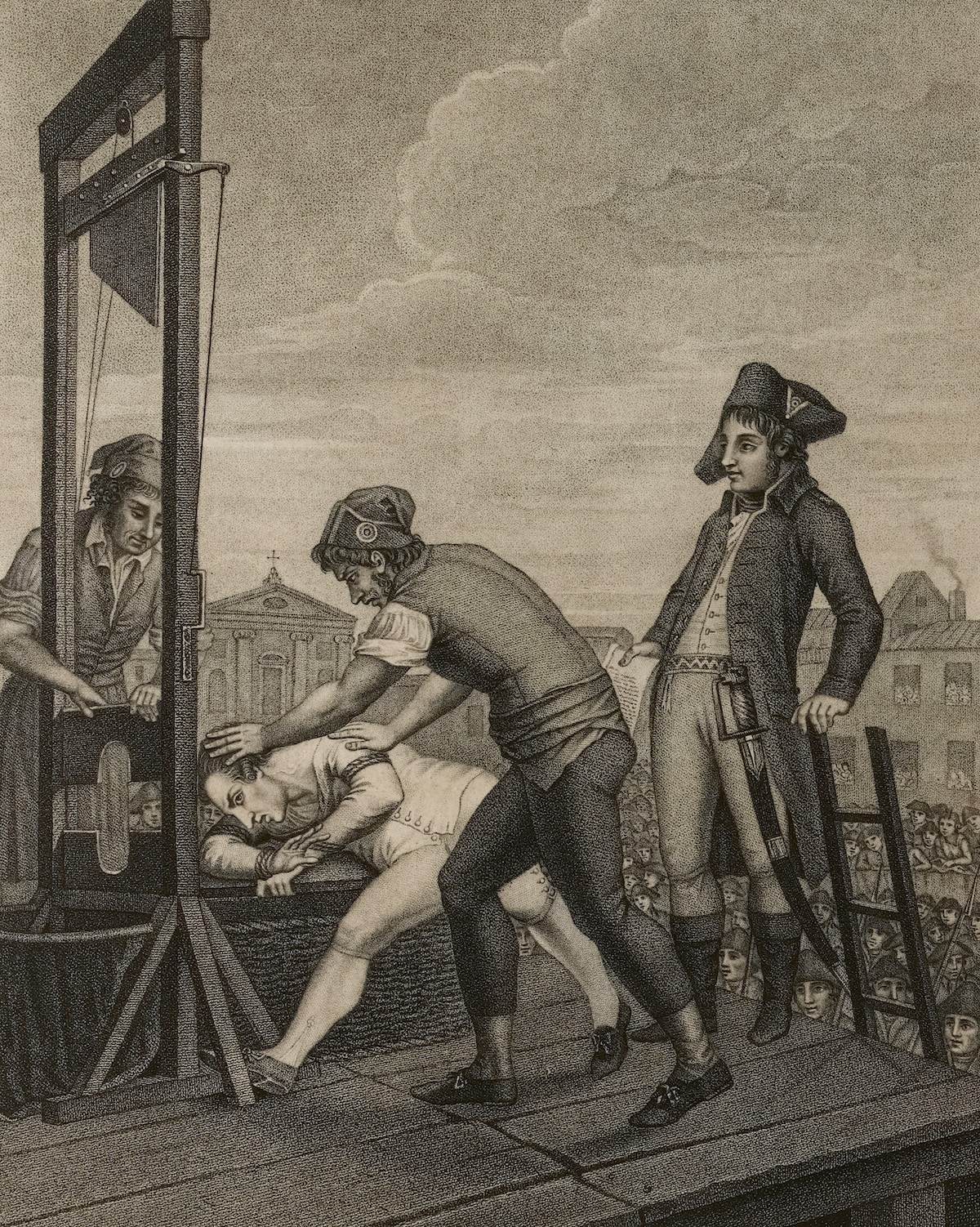

The Fall of Robespierre

The momentous final days of Maximilien Robespierre are well documented. Yet many of the established ‘facts’ about the Thermidorian Reaction are myths.

Tjournée (day of Revolutionary action), right-wing elements within the national assembly, or Convention, organised a coup d’état against Robespierre and his closest allies in the hall of the Convention, located within the Tuileries palace (adjacent to the Louvre). These men at once set out to end the Terror, which Robespierre had conducted over the previous year. They instituted the so-called ‘Thermidorian Reaction’, which moved government policies away from the social and political radicalism espoused by Robespierre‘s Revolutionary Government towards constitutional legalism and classically liberal economic policies. In the hours following the Thermidorian coup, Robespierre's supporters in the Paris Commune (the city’s municipal government, housed in the present-day Hôtel de Ville) had sought to organise armed resistance against the Convention among the city's sans-culottes, the street radicals who had been instrumental in bringing Robespierre to power during the crisis months of 1793, when France had been wracked by civil and foreign war.