The Cult of Edward the Confessor

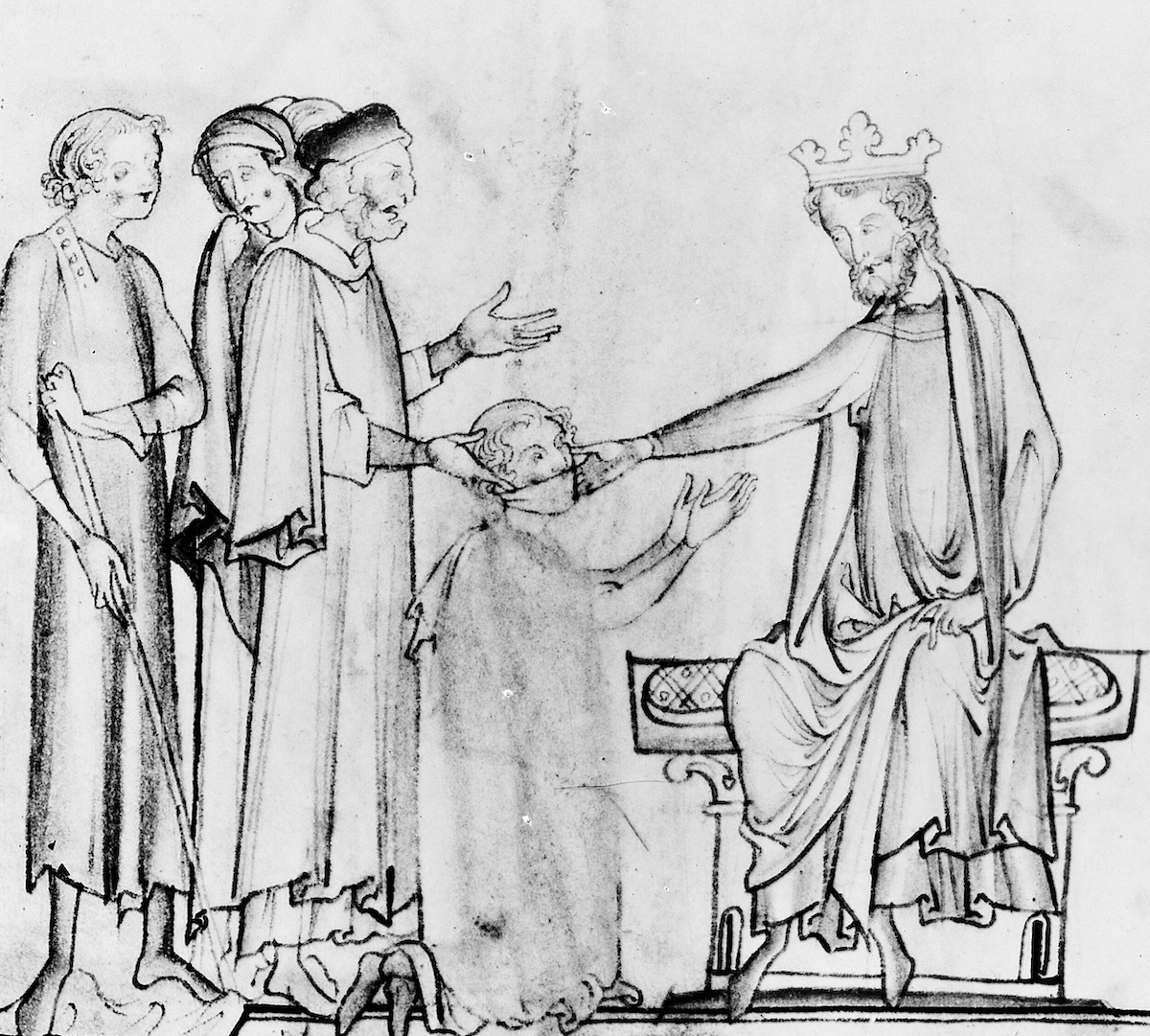

Edward the Confessor, the last truly Anglo-Saxon king of England, became an embodiment of pacific and idealistic medieval kingship under Henry III. Why?

Edward the Confessor was born between 1002 and 1005; he came to the English throne in 1042 and died early in 1066. The year 2005 has been declared to be the thousandth anniversary of his birth, and has been celebrated both in his birthplace of Islip, Oxfordshire, and in Westminster Abbey, his great foundation. Some have looked at the inexorable rise of the Danish House of Godwin, which culminated in Harold taking the throne in 1066, and seen Edward’s reign as a failure. A cosmopolitan, half-Norman monarch, Edward’s principal achievement is nevertheless held to have been the preservation of the unity of his kingdom. And he has always been acknowledged as the preserver of the ancient peace and harmony of a bygone England. But Edward was manifestly about other things too.