Captain Cook’s Contested Claim to Australia

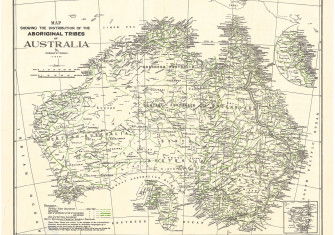

Terra nullius has long been at the heart of why the British did not treat with Aboriginal people following James Cook’s arrival in Australia. But should it be?

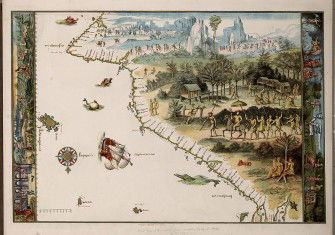

Two hundred and fifty years ago, on 22 August 1770, Captain James Cook claimed possession of much of the Australian continent in the name of George III. It is commonly believed that this act changed the course of the territory’s history. Yet Cook’s actions in Australia are a salient example of the old adage that the significance of an event often lies not so much in what happened as in what subsequent generations believe to have happened. In the course of time, Cook’s claiming of possession became shrouded in myth and misunderstanding.