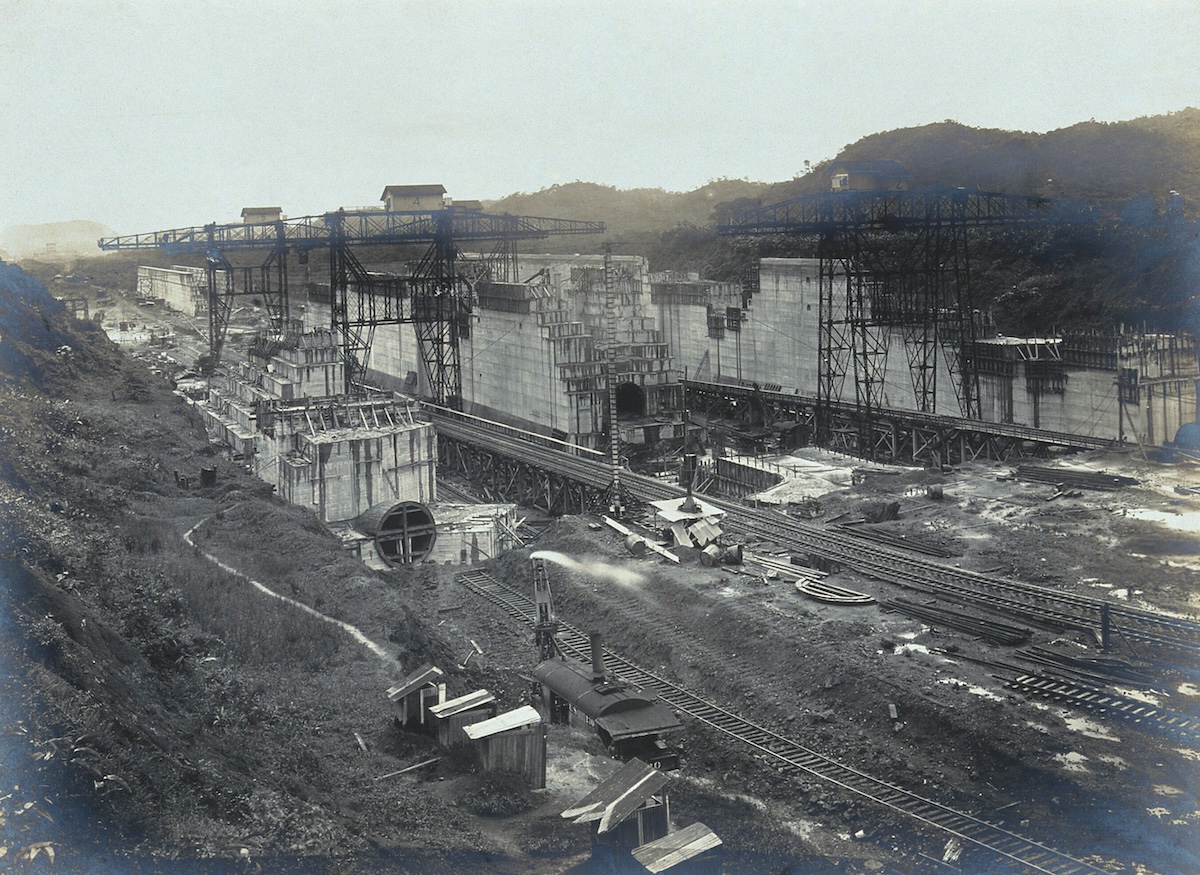

Building the Panama Canal

Though an incredible feat of engineering, the Panama Canal ruined many reputations during the 400 years it took to make the dream a reality.

It was supposed to have a glorious historical symmetry. August 2014, exactly a hundred years after the triumphant completion of the Panama Canal, should have seen the opening of the new $5.5bn expansion, one of the biggest engineering projects currently underway anywhere in the world. But the Panama Canal has broken men and reputations before. Amid strikes, huge cost overruns and rumours that the main construction consortium was in financial difficulty, the completion date slipped first to October, then to March 2015; now it is ‘mid 2016’. Each day of delay reportedly costs the canal company nearly a million dollars in lost revenue.