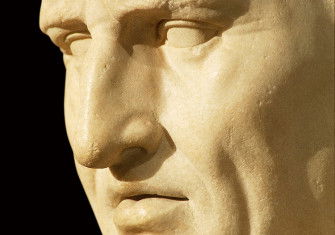

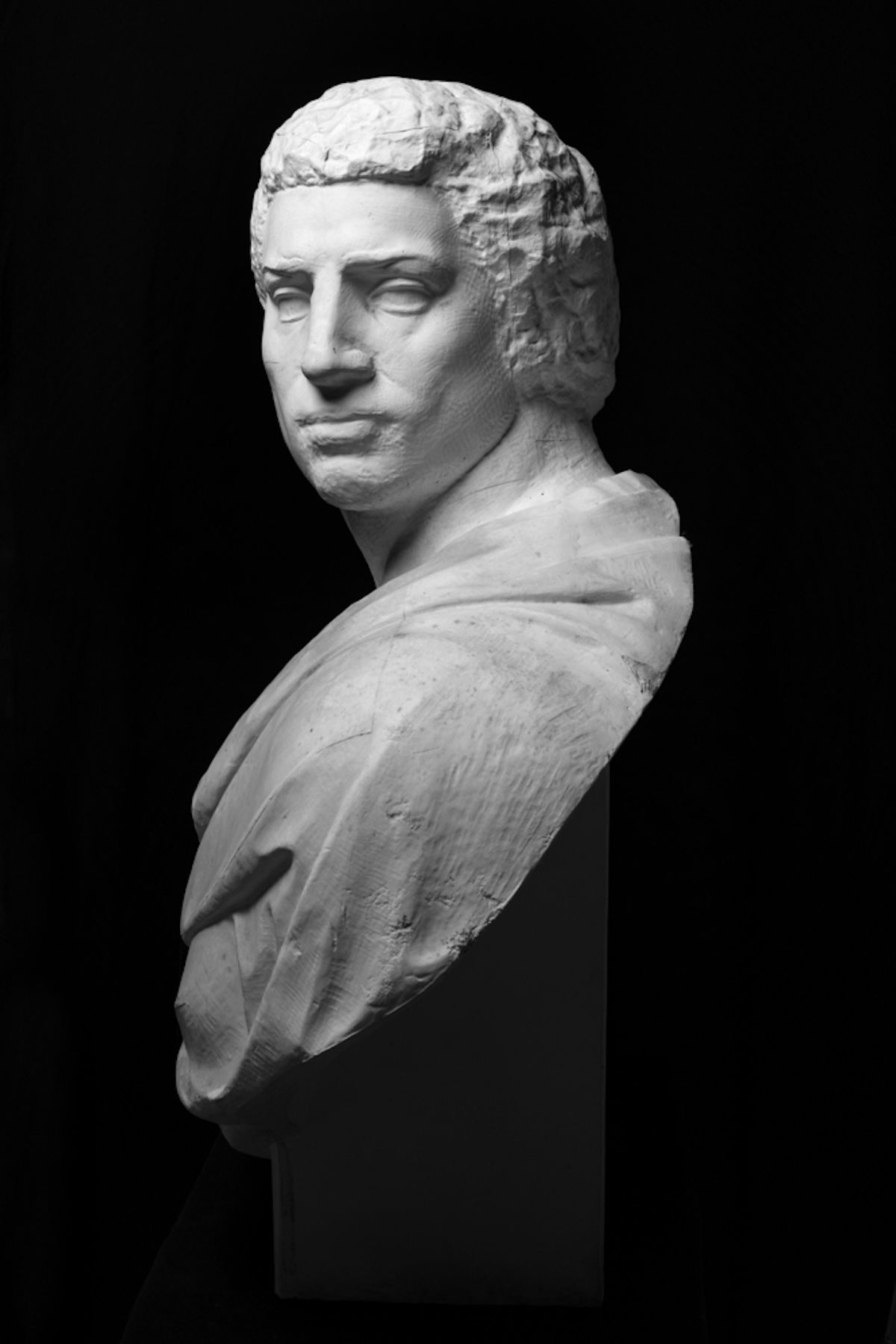

Was Brutus an Honourable Man?

Marcus Junius Brutus, the man who conspired to kill Julius Caesar, was not quite the friend to his fellow Romans that the legend suggests.

Mention the name of Brutus and, for many, it will bring to mind the Roman Republican who, desperate to preserve the constitution, committed murder with the noblest of intentions. The carefully considered assassination of Julius Caesar, a supposed tyrant in the making, is the deed for which Marcus Junius Brutus has gone down in history. This legendary act leaves us with the impression that Brutus was a nobleman of high moral standing and unbending principles, largely due to Shakespeare’s portrayal of him in Julius Caesar. But a survey of ancient sources reveals that this Brutus could, and often did, behave in questionable ways. Although the details of his life are often sketchy, there are several episodes that challenge his reputation as ‘an honourable man’. Furthermore, such behaviour occurs repeatedly, so his less-than-honourable nature cannot be written off as one uncharacteristic moment in an otherwise unblemished life.